Brain Under Fire: When Fever Turns to Seizure

Lucy Gaffneyboro

Illustrations by Cora Thompson

Amy Brown has been out sick from preschool for the past two days. Her parents assumed that her fever and runny nose were due to a common cold. But last night, as Amy’s dad finished tucking her into bed, she suddenly began to twitch violently and lost consciousness. Unbeknownst to her parents, Amy had suffered from a seizure: a transient episode of excessive and often synchronized electrical activity in the brain [1, 2]. When a seizure is provoked by a fever, it is referred to as a febrile seizure, an often benign phenomenon that commonly occurs in children under the age of five [3]. Even though young children frequently get fevers, only 2-5% develop febrile seizures [4]. Most children who have a febrile seizure will fully recover and have no further complications, but others may go on to experience recurrent episodes or chronic symptoms. In some cases, a febrile seizure can evolve into a more serious lifelong condition that impacts everyday life, begging the question: What are the underlying physiological and genetic factors that can predispose certain children to these chronic disorders?

Misfire in the Brain: What Leads to a Seizure?

Every brain is constantly thrumming with electrical activity that strives to regulate the body. Within the brain, cells called neurons transmit information through electrical signals [5]. Every neuron has a membrane potential, a voltage created by the unequal distribution of charged particles called ions across the neuronal membrane [6]. Typically, inactive neurons have a constant voltage called the resting membrane potential [7]. When a neuron is sufficiently stimulated by incoming signals from surrounding neurons, the flow of ions across the membrane changes [8]. If there is enough ion movement to significantly alter the voltage of the neuronal membrane, the cell becomes activated. Signals are then sent to adjacent neurons by chemical messengers called neurotransmitters [8, 9].

During a seizure, like the one that Amy experienced, the normal pattern of electrical signalling is disrupted [10]. Neurons become hyperexcitable, or overreactive, and are more likely to send out extraneous signals, leading to excessive and irregular electrical firing in the brain that is characteristic of a seizure [11]. All seizures are caused by the disruption of typical neuronal function, but different types of seizures can present with varied symptoms [12, 13, 14]. Some seizures appear more pronounced, potentially including a loss of consciousness, rapid jerking movements, or the body becoming either stiff or floppy [15]. These types of seizures are often seen in medical dramas. However, some seizures present more subtly, manifesting as occasional slight muscle twitching, a prolonged blank stare into space, or both [15]. Most seizures only last a few minutes [15]. If a seizure lasts longer than five minutes or consists of multiple recurrent seizure episodes without regaining full consciousness, it is classified as status epilepticus, a serious condition that requires immediate hospitalization [16, 17].

Burning Up: What is a Febrile Seizure?

After her seizure, Amy quickly regained consciousness, but her parents still brought her to the hospital for observation and treatment. Upon arrival, she was placed under the care of Dr. Bird, a neurologist, who worked to understand what happened in her brain and why.

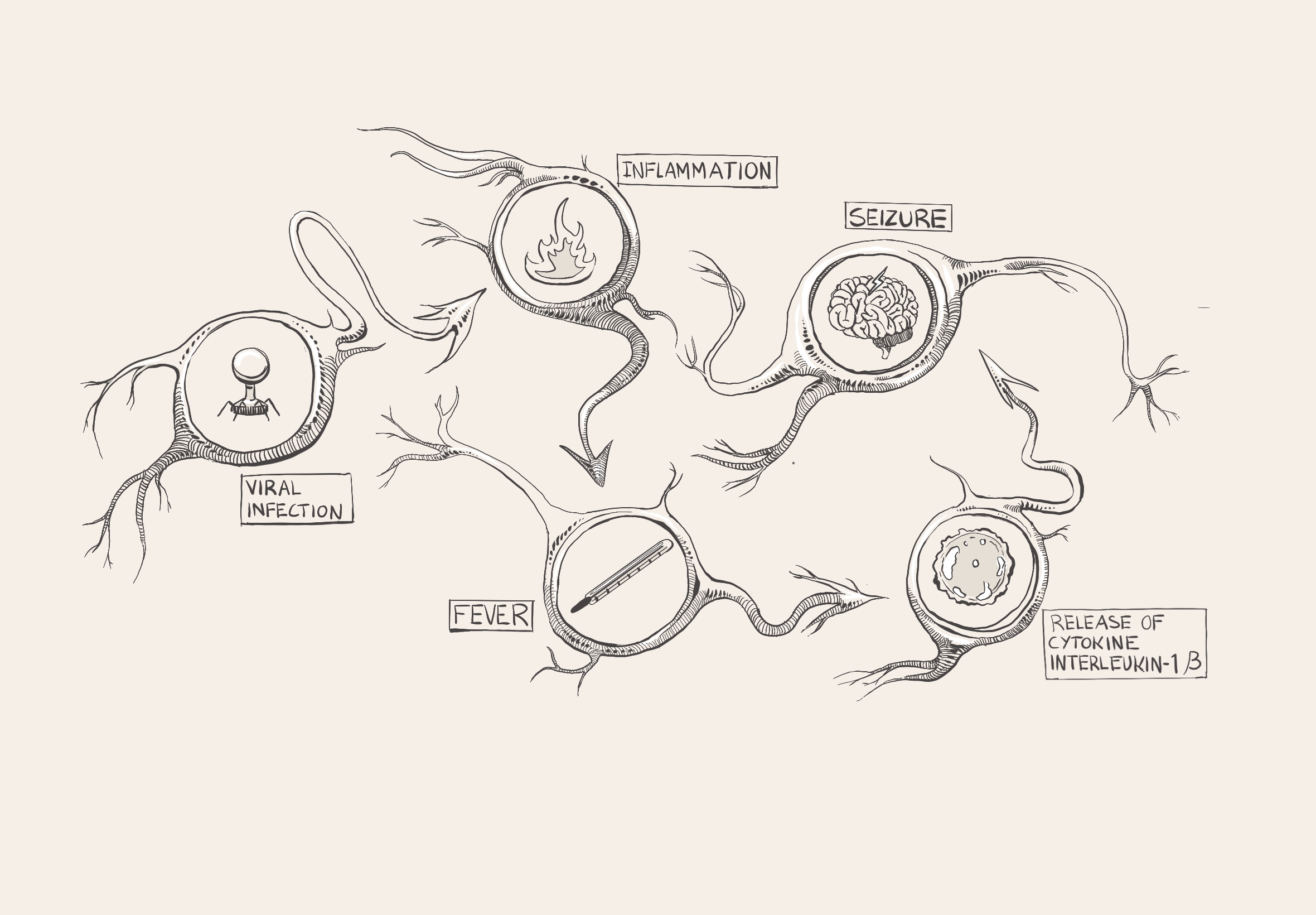

Amy had a temperature of 102°F before her seizure and was shivering, sweating, and feeling exhausted, so the doctors in the emergency room suspected that she had a viral infection [18]. During a viral infection, such as the flu, proteins called antibodies detect a virus in the body and trigger the immune system to respond [19]. Through a process called inflammation, immune cells are sent to attack the virus [20]. Inflammation stimulates the release of cytokines, which are small proteins that play many roles in the body and can indirectly affect how likely neurons are to become activated [20]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines ramp up immune activity to destroy the pathogen, whereas anti-inflammatory cytokines promote healing and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine pathways [20, 21]. Both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines are present in every immune response, and an equilibrium of cytokines is crucial to a healthy and functional immune system [20, 22]. Equilibrium does not necessarily mean completely equal levels of each type, but rather an ever-changing harmonization between the two [22].

A common byproduct of inflammation is fever, an immunological defense that limits bacterial and viral proliferation [23]. Although a fever defends against unwelcome pathogens, over time, the continuous immune response can wreak havoc by disrupting the body's carefully calibrated equilibrium [24]. During a fever, pro-inflammatory cytokines are released throughout the body [25]. For example, interleukin-1β increases the production and release of glutamate, a neurotransmitter that increases the likelihood of a neuron becoming activated [26, 27]. As glutamate levels rise, weak stimuli that do not typically change the membrane voltage end up prompting a neuronal response [14]. If enough hyperexcitable neurons are concentrated in one area of the brain, erratic electrical activity can compound and lead to a febrile seizure [28, 29]. If a febrile seizure lasts longer than five minutes, it is referred to as febrile status epilepticus (FSE) [30]. Keeping the possibility of FSE in mind, Dr. Bird walks into the exam room and consults Amy's chart. He sees that she had a high fever and tested positive for a viral infection. He considers her age and concludes that she had a febrile seizure, a seizure brought on by a fever greater than 100.4°F [13, 31]. Young children are more vulnerable to febrile seizures than other age groups since their nervous systems are still developing [29]. Given that this was Amy's first seizure, Dr. Bird explains to the Browns that this seizure increases her likelihood of having another.

Finding the Spark: Genetic Factors

Febrile seizures and their associated conditions sometimes have no known cause, but they can also be the result of a constellation of factors that make one brain more susceptible than another [13]. A family history of febrile seizures increases an individual’s chance of having one themselves, suggesting an underlying genetic basis for febrile seizure development [25, 32, 33]. Amy's mother also had a febrile seizure as a child, which Dr. Bird noted in his assessment [34]. One gene likely responsible for some of the hereditary patterns of febrile seizures is SCN1A, which helps control the construction of voltage-gated channels: special proteins that help modulate the membrane potential of a neuron [35]. A mutation in the SCN1A gene disrupts the flow of sodium ions through these channels, decreasing the brain’s ability to inhibit neurons and subsequently increasing the potential for neuronal hyperexcitability [35, 36, 37]. SCN1A mutations, therefore, elevate a person’s likelihood to experience a febrile seizure during a fever [36, 37]. Genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) is associated with mutations in the SCN1A gene and is an inherited disorder that encompasses several febrile seizure-related conditions [38, 39]. Around half of all children with GEFS+ have at least one parent with the same condition [39]. In addition to febrile seizures, individuals with GEFS+ experience febrile seizures plus (FS+), which are seizures that occur outside of the typical febrile seizure age range and are not caused by fevers [33, 40]. While most children will outgrow febrile seizures, children with GEFS+ will continue to have both recurrent FS+ and non-febrile seizures past age six [39]. In the next room over from Amy, Dr. Bird sees another one of his patients: Luke, an eight-month-old recently admitted for Dravet syndrome. A severe subtype of GEFS+, Dravet syndrome, affects one in 15,700 people, and its onset is often provoked by fevers in infancy [35, 41, 42]. The SCN1A mutation predisposes Luke to unnecessary pro-inflammatory responses; during a fever, his brain releases more pro-inflammatory cytokines than necessary [43]. In addition to fever, Dravet syndrome seizures can also be triggered by acute stress, sudden changes in temperature, or excitement as a result of SCN1A gene dysfunction [44]. Despite similarities in the underlying mechanisms of febrile seizure and Dravet syndrome, the latter seizures are harder to regulate and treat because the threshold for neuronal excitement is lower [45, 46].

After the Fire: Long-Term Effects of Febrile Seizure

When a status epilepticus seizure or an FSE rages for several minutes, there is a chance that the harm caused to the brain can be irreversible, leading to lifelong medical complications [47, 48]. For example, temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is caused by abnormal electrical signaling in the temporal lobe, a brain region crucial to language, emotion, visual recognition, and memory [49, 50, 51]. In the long term, TLE can cause cognitive decline and even the development of disorders such as depression and anxiety [52]. Additionally, TLE can negatively affect executive functions such as memory, planning, and attention, making it more challenging to maintain social relationships, manage time, and control impulses [52, 53]. Within the temporal lobe is the hippocampus, a structure integral to short and long-term memory, spatial awareness, and emotional memory [54]. Damage to the hippocampus can result in memory impairment [55]. Recent research has investigated the relationship between the structure and orientation of the hippocampus and the occurrence of FSE [56]. Hippocampal malrotation (HIMAL) is a condition that describes an abnormally positioned hippocampus, and it can be an indicator of abnormal brain development that can predispose individuals to seizures [57]. Individuals could be born with HIMAL, or HIMAL could arise after a seizure [57]. HIMAL is predominantly observed in patients who have had an FSE as opposed to those who have had a febrile seizure, and it may play a role in the development of TLE [57]. Reduced hippocampal size also predisposes individuals to febrile seizures and FSE development, and children with FSE have higher rates of internal hippocampal injury; however, it is unclear whether the damage preceded the seizure or whether the seizure caused the damage [25, 58].

We Didn’t Start the FIRES

Dr. Bird's schedule is packed. His next patient is a seven-year-old boy named Harry, who was previously healthy without any neurological illnesses. One week ago, Harry developed a fever and a sore throat, so his parents brought him to be seen by his primary care doctor, who gave him medicine to treat his respiratory infection. After many days, some of his symptoms resolved, but his fatigue and fever lingered, and Harry was admitted to the hospital. Several days into his hospital stay, he started having refractory status epilepticus, which are seizures that cannot be stopped after treatment with two or more medications [33]. Dr. Bird and his team concluded that Harry was suffering from febrile-infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). FIRES is a chronic, sudden-onset epilepsy condition that arises after a fever caused by an infection [59]. The key difference between FIRES and an FSE or febrile seizures is that FIRES is often accompanied by lifelong after-effects [60]. FIRES can cause refractory status epilepticus that arises between twenty-four hours to two weeks after the onset of a fever, just like Harry experienced [61]. A fever is a marker of the body’s immune system protecting against pathogens with inflammation, but excessive inflammation in the brain can induce seizures, which in turn provoke more inflammation [23, 62]. Individuals with FIRES are often found to have increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β [63]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines trigger the release of even more pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to a cytokine storm [64]. The massive increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines causes increased excitability of neurons and subsequent exacerbation of seizures [65, 66]. FIRES is most commonly observed in children of elementary school age, like Harry, but it can affect individuals from infancy to adolescence [33, 67]. Patients continue to suffer from progressively debilitating seizures throughout their lives; damage to their brains is significant [68]. As a result, FIRES can cause neurological symptoms like memory loss and behavioral problems [69].

Putting Out the Flame

When Amy arrived at the hospital, she was first given medication, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, to control her fever [4, 42, 70]. If the seizure had been an FSE, the dose of acetaminophen would have been followed by a depressant medication such as a benzodiazepine to slow the nervous system by preventing hyperexcitable neuronal firing, which terminates the seizure [30]. If seizure activity hadn’t stopped after the first dose of benzodiazepine, additional doses would have been given [30]. Most children who have a seizure will experience no long-term complications, but immediate medical attention is crucial to ensure a full recovery [3, 71]. Unlike febrile seizures and FSE, FIRES has a different treatment plan: cytokine-directed immunotherapy (CDI), which uses the body's own molecular components and processes to modulate cytokine activity [28, 72]. CDI is individualized: One person’s treatment could focus on increasing levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines while another person’s could focus on increasing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [72]. CDI is used for a variety of conditions, and it can be incredibly successful in treating FIRES by targeting specific cytokines that are key to regulating inflammation [28, 72]. During Harry's hospital stay, he was treated with a CDI drug called Anakinra IL-1 to block pro-inflammatory IL-1 receptors [28, 72]. When IL-1 receptors are blocked, inflammatory cytokines cannot bind to them, which reduces seizure propagation [73]. Anakinra IL-1 can be used over long periods of time for chronic inflammatory conditions, and Harry will likely receive this medication for up to a year [74]. Another common drug used for CDI is Tocilizumab, an antibody that binds to a different pro-inflammatory receptor site and prevents that pro-inflammatory cytokine from further activating more immune cells [28].

Firefighting: Caring for Febrile Seizures

Amy, Luke, and Harry all had fevers, and their haywire immune responses produced a myriad of side effects, ultimately resulting in febrile seizures. Dr. Bird's patients showcase how febrile seizures range from benign and temporary to life-threatening and chronic. Pronounced seizures like the ones that Luke and Harry experienced are well-documented in the media, but their prevalence on page and screen belies their relative rarity. More common instances of seizures, such as Amy's febrile seizure, are shorter, less consequential, and less dramatic; however, they can still be traumatic and alarming to both patients and their family members. All seizures are the result of the same core physiological vulnerability: a brain temporarily pushed to the brink by neuronal hyperexcitability. In the cases of Amy, Luke, and Harry, their brains were also the victims of fever and inflammation, but the extent to which genetics and family history contributed to their conditions remains unknown. Although Dr. Bird is fictional, real-life physicians treat people who experience brief febrile seizures and others with lifelong neurological challenges. These physicians must effectively communicate with patients and families while balancing the nuances between each condition to provide the best treatment.

References

Fisher, R. S., Cross, J. H., French, J. A., Higurashi, N., Hirsch, E., Jansen, F. E., Lagae, L., Moshé, S. L., Peltola, J., Roulet Perez, E., Scheffer, I. E., & Zuberi, S. M. (2017). Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia, 58(4), 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13670

Stafstrom, C. E., & Carmant, L. (2015). Seizures and Epilepsy: an Overview for Neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 5(6), a022426–a022426. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a022426

Eilbert, W., & Chan, C. (2022). Febrile seizures: A review. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12769

Tiwari, A., Meshram, R. J., & Kumar Singh, R. (2022). Febrile Seizures in children: a Review. Cureus, 14(11). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.31509

Faber, D. S., & Pereda, A. E. (2018). Two Forms of Electrical Transmission Between Neurons. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2018.00427

Raghavan, M., Fee, D., & Barkhau, P. (2019). Generation and propagation of the action potential. In K. Levin & P. Chauvel (Eds.), Clinical neurophysiology : basis and technical aspects (pp. 3–22). Amsterdam Elsevier.

Khadria, A. (2022). Tools to measure membrane potential of neurons. Biomedical Journal, 45(5), 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2022.05.007

Drukarch, B., & Micha M.M. Wilhelmus. (2023). Thinking about the action potential: the nerve signal as a window to the physical principles guiding neuronal excitability. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2023.1232020

Zbili, M., Rama, S., & Debanne, D. (2016). Dynamic Control of Neurotransmitter Release by Presynaptic Potential. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2016.00278

Doubovikov, E. D., Serdyukova, N. A., Greenberg, S. B., Gascoigne, D. A., Minhaj, M. M., & Aksenov, D. P. (2023). Electric Field Effects on Brain Activity: Implications for Epilepsy and Burst Suppression. Cells, 12(18), 2229–2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12182229

Kopf, M., Martini, J., Stier, C., Ethofer, S., Braun, C., Li Hegner, Y., Focke, N. K., Marquetand, J., & Helfrich, R. F. (2024). Aperiodic activity indexes neural hyperexcitability in generalized epilepsy. Eneuro, 11(9), ENEURO.0242-24.2024. https://doi.org/10.1523/eneuro.0242-24.2024

Smith, D. K., Sadler, K. P., & Benedum, M. (2019). Febrile Seizures: Risks, Evaluation, and Prognosis. American Family Physician, 99(7), 445–450. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30932454/

Leung, A. K., Hon, K. L., & Leung, T. N. (2018). Febrile seizures: an overview. Drugs in Context, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.212536

Mosili, P., Maikoo, S., Mabandla, M., Vuyisile, & Qulu, L. (2020). The Pathogenesis of Fever-Induced Febrile Seizures and Its Current State. Neuroscience Insights, 15(15). https://doi.org/10.1177/2633105520956973

Chang, R. S., Leung, C. Y. W., Ho, C. C. A., & Yung, A. (2017). Classifications of seizures and epilepsies, where are we? – A brief historical review and update. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 116(10), 736–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2017.06.001

Horváth, L., Fekete, I., Molnár, M., Válóczy, R., Márton, S., & Fekete, K. (2019). The Outcome of Status Epilepticus and Long-Term Follow-Up. Frontiers in Neurology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00427

Trinka, E., Cock, H., Hesdorffer, D., Rossetti, A. O., Scheffer, I. E., Shinnar, S., Shorvon, S., & Lowenstein, D. H. (2015). A definition and classification of status epilepticus - Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia, 56(10), 1515–1523. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13121

Corsello, A., Maria Beatrice Marangoni, Macchi, M., Cozzi, L., Agostoni, C., Gregorio Paolo Milani, & Dilena, R. (2024). Febrile Seizures: A Systematic Review of Different Guidelines. Pediatric Neurology, 155, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2024.03.024

Murin, C. D., Wilson, I. A., & Ward, A. B. (2019). Antibody responses to viral infections: a structural perspective across three different enveloped viruses. Nature Microbiology, 4(5), 734–747. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0392-y

Kany, S., Vollrath, J. T., & Relja, B. (2019). Cytokines in Inflammatory Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(23), 6008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20236008

Al-Qahtani, A. A., Alhamlan, F. S., & Al-Qahtani, A. A. (2024). Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins in Infectious Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 9(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9010013

Cicchese, J. M., Evans, S., Hult, C., Joslyn, L. R., Wessler, T., Millar, J. A., Marino, S., Cilfone, N. A., Mattila, J. T., Linderman, J. J., & Kirschner, D. E. (2018). Dynamic balance of pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory signals controls disease and limits pathology. Immunological Reviews, 285(1), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12671

Evans, S. S., Repasky, E. A., & Fisher, D. T. (2015). Fever and the thermal regulation of immunity: the immune system feels the heat. Nature Reviews Immunology, 15(6), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3843

Han, L., Wu, T., Zhang, Q., Qi, A., & Zhou, X. (2025). Immune Tolerance Regulation Is Critical to Immune Homeostasis. Journal of Immunology Research, 2025(1). https://doi.org/10.1155/jimr/5006201

Sawires, R., Buttery, J., & Fahey, M. (2022). A Review of Febrile Seizures: Recent Advances in Understanding of Febrile Seizure Pathophysiology and Commonly Implicated Viral Triggers. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9(1), 801321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.801321

Pal, M. M. (2021). Glutamate: the Master Neurotransmitter and Its Implications in Chronic Stress and Mood Disorders. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15(15). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.722323

Zhang, N., Song, Y., Wang, H., Li, X., Lyu, Y., Liu, J., Mu, Y., Wang, Y., Lu, Y., Li, G., Fan, Z., Wang, H., Zhang, D., & Li, N. (2024). IL-1β promotes glutamate excitotoxicity: indications for the link between inflammatory and synaptic vesicle cycle in Ménière’s disease. Cell Death Discovery, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-02246-2

Goh, Y., Sen Hee Tay, Leong, L., & Rahul Rathakrishnan. (2023). Bridging the Gap: Tailoring an Approach to Treatment in Febrile Infection‐Related Epilepsy Syndrome. Neurology, 100(24), 1151–1155. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000207068

Han, J. Y., & Han, S. B. (2023). Pathogenetic and etiologic considerations of febrile seizures. Clinical and Experimental Pediatrics, 66(2), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2021.01039

Ferretti, A., Riva, A., Fabrizio, A., Bruni, O., Capovilla, G., Foiadelli, T., Orsini, A., Raucci, U., Romeo, A., Striano, P., & Parisi, P. (2024). Best practices for the management of febrile seizures in children. The Italian Journal of Pediatrics/Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 50(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-024-01666-1

Wang, Y., Trevelyan, A. J., Valentin, A., Alarcon, G., Taylor, P. N., & Kaiser, M. (2017). Mechanisms underlying different onset patterns of focal seizures. PLOS Computational Biology, 13(5), e1005475. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005475

Kumar, N., Midha, T., & Rao, Y. K. (2019). Risk Factors of Recurrence of Febrile Seizures in Children in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kanpur: A One Year Follow Up Study. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 22(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.4103/aian.AIAN_472_17

Pavone, P., Pappalardo, X. G., Parano, E., Falsaperla, R., Marino, S. D., Fink, J. K., & Ruggieri, M. (2022). Fever-Associated Seizures or Epilepsy: An Overview of Old and Recent Literature Acquisitions. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.858945

Permana, I., Meyrisa, N., & Brajadenta, G. (2025). The Effect of Family History of Seizures as A Risk Factor for The Inci-dence of Recurrent Febrile Seizures and Types of Febrile Seizures in Children at Waled Cirebon Hospital. Eduvest, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.59188/eduvest.v5i4.25530

Ding, J., Li, X., Tian, H., Wang, L., Guo, B., Wang, Y., Li, W., Wang, F., & Sun, T. (2021). SCN1A Mutation—Beyond Dravet Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 743726. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.743726

Bender, A. C., Morse, R. P., Scott, R. C., Holmes, G. L., & Lenck-Santini, P.-P. (2012). SCN1A mutations in Dravet syndrome: Impact of interneuron dysfunction on neural networks and cognitive outcome. Epilepsy & Behavior, 23(3), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.11.022

Ademuwagun, I. A., Rotimi, S. O., Syrbe, S., Ajamma, Y. U., & Adebiyi, E. (2021). Voltage Gated Sodium Channel Genes in Epilepsy: Mutations, Functional Studies, and Treatment Dimensions. Frontiers in Neurology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.600050

Wu, Y. W., Sullivan, J., McDaniel, S. S., Meisler, M. H., Walsh, E. M., Li, S. X., & Kuzniewicz, M. W. (2015). Incidence of Dravet Syndrome in a US Population. Pediatrics, 136(5), e1310–e1315. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1807

Camfield, P., & Camfield, C. (2015). Febrile seizures and genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+). Epileptic Disorders, 17(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2015.0737

Myers, K. A., Scheffer, I. E., & Berkovic, S. F. (2018). Genetic literacy series: genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Epileptic Disorders, 20(4), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2018.0985

Ram, D., & Newton, R. (2015). The Genetics of Febrile Seizures. Pediatric Neurology Briefs, 29(12), 90. https://doi.org/10.15844/pedneurbriefs-29-12-1

Wu, C., Wang, Q., Li, W., Han, M., Zhao, H., & Xu, Z. (2024). Research progress on pathogenesis and treatment of febrile seizures. Life Sciences, 362, 123360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2024.123360

Kwon, A., Kwak, B. O., Kim, K., Ha, J., Kim, S.-J., Bae, S. H., Son, J. S., Kim, S.-N., & Lee, R. (2018). Cytokine levels in febrile seizure patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Seizure, 59, 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2018.04.023

Okudan, Z. V., & Ozkara, C. (2018). Reflex epilepsy: triggers and management strategies. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Volume 14, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s107669

Zhang, G., Huang, S., Wei, M., Wu, Y., Xie, Z., & Wang, J. (2025). Dravet syndrome: novel insights into SCN1A-mediated epileptic neurodevelopmental disorders within the molecular diagnostic-therapeutic framework. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2025.1634718

Ballesteros-Sayas, C., Muñoz-Montero, A., Giorgi, S., Cardenal-Muñoz, E., Turón-Viñas, E., Pallardó, F., & José Ángel Aibar. (2024). Non-pharmacological therapeutic needs in people with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy & Behavior, 150, 109553–109553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109553

Heuser, K., Horn, M., Samsonsen, C., Ulvin, L. B., Olsen, K. B., Power, K. N., Veiby, G., Molteberg, E., Engelsen, B., & Taubøll, E. (2024). Treating status epilepticus in adults. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Legeforening, 144. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.23.0782

Specchio, N., & Auvin, S. (2025). To what extent does status epilepticus contribute to brain damage in the developmental and epileptic Encephalopathies. Epilepsy & Behavior, 164, 110271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2025.110271

Pack, A. M. (2019). Epilepsy Overview and Revised Classification of Seizures and Epilepsies. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, 25(2), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1212/con.0000000000000707

Zachlod, D., Kedo, O., & Amunts, K. (2022). Anatomy of the temporal lobe: From macro to micro. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 187, 17–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823493-8.00009-2

Gao, Y., Su, Q., Liang, L., Yan, H., & Zhang, F. (2022). Editorial: Temporal lobe dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1077398

Vinti, V., Dell’Isola, G. B., Tascini, G., Mencaroni, E., Cara, G. D., Striano, P., & Verrotti, A. (2021). Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and Psychiatric Comorbidity. Frontiers in Neurology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.775781

Cristofori, I., Cohen-Zimerman, S., & Grafman, J. (2019). Executive functions. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 163(3), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804281-6.00011-2

Chauhan, P., Jethwa, K., Rathawa, A., Chauhan, G., & Mehra, S. (2021). Cerebral Ischemia. In Exon Publications eBooks. Exon Publications. https://doi.org/10.36255/exonpublications.cerebralischemia.2021

Cutsuridis, V., & Yoshida, M. (2017). Editorial: Memory Processes in Medial Temporal Lobe: Experimental, Theoretical and Computational Approaches. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2017.00019

Chan, S., Bello, J. A., Shinnar, S., Hesdorffer, D. C., Lewis, D. V., MacFall, J., Shinnar, R. C., Gomes, W., Litherland, C., Xu, Y., Nordli, D. R., Pellock, J. M., Frank, L. M., Moshé, S. L., Sun, S., & FEBSTAT Study Team. (2015). Hippocampal Malrotation Is Associated With Prolonged Febrile Seizures: Results of the FEBSTAT Study. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology, 205(5), 1068–1074. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.14.13330

Fu, T.-Y., Ho, C.-R., Lin, C.-H., Lu, Y.-T., Lin, W.-C., & Tsai, M.-H. (2021). Hippocampal Malrotation: A Genetic Developmental Anomaly Related to Epilepsy? Brain Sciences, 11(4), 463–463. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11040463

Feyissa, A. M. (2024). Have We Solved the Chicken-and-Egg Conundrum? Hippocampal Sclerosis and Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Following Febrile Status Epilepticus: Results of the 10-Year Follow-up FEBSTAT Study. Epilepsy Currents, 24(6), 400–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/15357597241279746

deCampo, D., Xian, J., Karlin, A., Katie Rose Sullivan, Ruggiero, S. M., Galer, P. D., Ramos, M., Abend, N. S., Gonzalez, A., & Helbig, I. (2023). Investigating the genetic contribution in febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome and refractory status epilepticus. Frontiers in Neurology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1161161

Shi, X., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Kang, X., Yang, F., Yuan, F., & Jiang, W. (2023). Long-term outcomes of adult cryptogenic febrile infection–related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). Frontiers in Neurology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.1081388

Pavone, P., Corsello, G., Raucci, U., Lubrano, R., Enrico Parano, Ruggieri, M., Greco, F., Marino, S., & Raffaele Falsaperla. (2022). Febrile infection-related Epilepsy Syndrome (FIRES): a severe encephalopathy with status epilepticus. Literature review and presentation of two new cases. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 48(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01389-1

Li, W., Wu, J., Zeng, Y., & Zheng, W. (2023). Neuroinflammation in epileptogenesis: from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. Frontiers in Immunology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1269241

Clarkson, B. D., LaFrance-Corey, R. G., Kahoud, R. J., Farias-Moeller, R., Payne, E. T., & Howe, C. L. (2019). Functional deficiency in endogenous interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist in patients with febrile infection‐related epilepsy syndrome. Annals of Neurology, 85(4), 526–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25439

Jarczak, D., & Nierhaus, A. (2022). Cytokine Storm—Definition, Causes, and Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(19), 11740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911740

Wolinski, P., Ksiazek-Winiarek, D., & Glabinski, A. (2022). Cytokines and Neurodegeneration in Epileptogenesis. Brain Sciences, 12(3), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12030380

Liu, L., Han, X., Huang, Q., Zhu, X., Yang, J., & Liu, H. (2016). Increased neuronal seizure activity correlates with excessive systemic inflammation in a rat model of severe preeclampsia. Hypertension Research, 39(10), 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2016.53

van Baalen, A. (2023). Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome in childhood: A clinical review and practical approach. Seizure, 111, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2023.09.008

Serino, D., Santarone, M., Caputo, D., & Fusco, L. (2019). Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES): prevalence, impact and management strategies. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Volume 15, 1897–1903. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s177803

Khair, A. M., & Elmagrabi, D. (2015). Febrile Seizures and Febrile Seizure Syndromes: An Updated Overview of Old and Current Knowledge. Neurology Research International, 2015, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/849341

Tan, E., Braithwaite, I., McKinlay, C. J. D., & Dalziel, S. R. (2020). Comparison of Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) With Ibuprofen for Treatment of Fever or Pain in Children Younger Than 2 Years. JAMA Network Open, 3(10). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22398

Peng, P., Peng, J., Yin, F., Deng, X., Chen, C., He, F., Wang, X., Guang, S., & Mao, L. (2019). Ketogenic Diet as a Treatment for Super-Refractory Status Epilepticus in Febrile Infection-Related Epilepsy Syndrome. Frontiers in Neurology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00423

Harrar, D. B., Genser, I., Najjar, M., Davies, E., Sule, S., Wistinghausen, B., Goldbach-Mansky, R., & Wells, E. (2024). Successful Management of Febrile Infection–Related Epilepsy Syndrome Using Cytokine-Directed Therapy. Journal of Child Neurology, 39(11-12), 440–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/08830738241273448

Lai, Y., Muscal, E., Wells, E., Shukla, N., Eschbach, K., Hyeong Lee, K., Kaliakatsos, M., Desai, N., Wickström, R., Viri, M., Freri, E., Granata, T., Nangia, S., Dilena, R., Brunklaus, A., Wainwright, M. S., Gorman, M. P., Stredny, C. M., Asiri, A., & Hundallah, K. (2020). Anakinra usage in febrile infection related epilepsy syndrome: an international cohort. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, 7(12), 2467–2474. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51229

Westbrook, C., Subramaniam, T., Seagren, R. M., Tarula, E., Co, D., Furstenberg-Knauff, M., Wallace, A., & Hsu, D. (2019). Febrile Infection-Related Epilepsy Syndrome (FIRES) Treated Successfully With Anakinra In A 21-Year-Old Woman. WMJ : Official Publication of the State Medical Society of Wisconsin, 118(3), 135. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7082129/