It Takes a Microbial Village: Maternal Microbiota and Neonatal Neurodevelopment

Janessa Ya

Illustrations by Elizabeth Catizone

*Note: This article uses female-gendered language to refer to pregnant and postpartum people due to the vast majority of cited literature being focused on female-identifying subjects. The editors wish to acknowledge that pregnancy is independent of gender identity.

What if someone told you that since the moment you were born, and possibly even before that, tiny creatures have been living throughout your body, quietly helping you go about your life? No, it’s not your fairy godmother; it’s microbes! Microbes are microscopic organisms that are undetectable to the naked eye, yet have an enormous impact on human lives [1, 2]. You may know microbes as the cause of some diseases, but the majority of microbes are harmless and are actually beneficial [3, 4]. In particular, microbes residing in the gut are integral to human health [5, 6]. However, the impacts of microbes are not limited to the host they inhabit; they can even shape the health of future generations through the maternal-fetal relationship [7]. Maternal microbiota — referring to all of the microbes of a mother — can influence neurodevelopment both before and after birth, highlighting how bacteria support human function from the earliest stages of development [8]. To understand how maternal microbiota may affect neonatal brain development, it is essential first to become familiar with the microbial communities that inhabit the human body and their unique characteristics.

Welcome to the Village: The Gut’s Gated Community

When you eat, you are not only providing sustenance for your body, but also for the trillions of microbes that live inside you [9]. The human body harbors various communities of microbes, and the gut microbiome is home to the most concentrated one [2]. The human gut microbiome refers to the collection of microorganisms that live in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which consists of the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine [10]. Much like a natural ecosystem, the gut microbiome relies on intricate interactions among its microbes to maintain balance and function [11]. Microbes live together in much the same way that organisms coexist in a coral reef: coral rely on algae for energy, algae rely on fish waste for nutrients, and fish rely on coral for shelter, maintaining an optimal and delicate harmony [12]. If an invasive species, such as a lionfish, were introduced to the reef, the balance would unravel — smaller fish would vanish, algae would overgrow, and the coral would begin to die off, destabilizing the entire ecosystem [13]. Similarly, proper functioning of the gut microbiome depends on symbiotic interactions between the host and other microbes [5, 14]. For example, the bacteria Oxalobacter formigenes break down oxalate, a compound that can lead to kidney stone development, and in return, the bacteria gain nutrients and energy from the host [15, 16]. The gut microbiome is both dynamic and interdependent, and even minor disturbances can contribute to extremely detrimental effects [5].

Despite the misconception that all bacteria are harmful, microbes throughout the body have developed mutually beneficial relationships with their hosts that are crucial for the survival of both [ 4,9]. Gut microbiota help maintain a stable internal environment in the body, defend against foreign invaders, and synthesize metabolites — small molecules that support digestion, immunity, and communication between cells [17, 18]. In addition, gut microbiota are involved in regulating the immune response, wherein the body recognizes, identifies, and eliminates foreign substances while supplying essential nutrients like vitamins [9,19]. The specific composition of microbial species in the gut varies considerably between individuals and is influenced by factors like diet, environment, and lifestyle, each of which introduces new microbes and shapes the microbial community of the GI tract [9, 20]. Although no two people share the same microbial species composition, the bacteria generally perform similar functions across all individuals [9, 21].

Disaster Strikes the Gut Community

A balanced gut microbiome facilitates proper bodily functions, while deviations can be detrimental to overall health [22]. Disruption of this balance can lead to gut dysbiosis, a condition in which the composition or function of the gut microbiome is altered due to a loss of beneficial bacteria, an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, or a reduction in the variety of microorganisms present [22, 23]. Specifically, pathogenic bacteria cause disease, whereas non-pathogenic bacteria generally do not harm their host [24, 25]. One pathogenic bacterium that can cause infection is Clostridiodes difficile, which infects the gut microbiome and induces diarrhea and other severe intestinal issues [26, 27]. However, when the host is in a weakened state, even non-pathogenic bacteria can become dangerous by attacking the host and causing illness [25, 28]. Maintaining microbial balance requires several physical and chemical defenses. For example, the mucus layer, which coats the intestinal cell surface, serves as the first line of defense against pathogenic bacteria and protects the gut lining [29, 30]. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) inhabits the mucus layer and typically aids in the processing and digestion of carbohydrates like fiber, starches, and sugars [31, 32]. During periods of prolonged carbohydrate deficiency, B. theta may begin degrading the gut’s sugar-composed mucus layer, making the host more susceptible to infection. Therefore, even beneficial bacteria like B. theta can contribute to dysbiosis when environmental or nutritional imbalances disrupt the gut microbiome [30].

Another Bombshell Enters the Village: the Vaginal Microbiome

Microbiomes exist in multiple locations throughout the body, not just the gut. The vaginal microbiome is another finely tuned ecosystem where microbial balance plays a crucial protective role [33]. In both pregnant and non-pregnant women, the vaginal microbiome is typically dominated by the Lactobacillus genus, which is the primary producer of lactic acid, thereby lowering vaginal pH and limiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria [34, 35]. Beneficial vaginal microbes thrive in acidic conditions, whereas many pathogenic bacteria struggle to survive [35]. In addition to acidifying the environment, lactic acid possesses antimicrobial properties that selectively target and eliminate pathogenic bacteria [36]. Together, conditions created by lactic acid cultivate an inhospitable environment that prevents pathogenic bacteria from growing, thereby protecting vaginal health [37]. Just like the gut microbiome, the vaginal microbiome can experience dysbiosis [38]. Vaginal dysbiosis can manifest as bacterial vaginosis (BV), an infection that causes pain and discomfort in the vagina [39]. BV, characterized by a reduction in Lactobacillus, lowers vaginal acidity, which enables potentially pathogenic microbes to proliferate within the vagina [40]. BV increases the risk for sexually transmitted infections and pelvic inflammatory disease, an infection in the upper genital tract [41]. For pregnant women, BV has been linked to detrimental birth outcomes, including pre-term birth, low birth weight, and miscarriage [33].

Microbial Mutiny: Dual Dysbiosis Threatens Pregnancy

The delicate equilibrium of the vaginal microbiome mirrors that of the gut, and the two systems are more closely connected than they might appear. Emerging evidence indicates that there is continuous microbial exchange and communication between the gut and vagina [42]. Picture the Galápagos Islands: each island has its unique ecosystem, but microbes — like the Galápagos birds — can travel between them [36]. For instance, evidence suggests that vaginal Lactobacillus may have originated in the gut. Vaginal dysbiosis and gut dysbiosis work in tandem to trigger an inflammatory immune response that can contribute to serious pregnancy complications: gut dysbiosis allows bacteria to enter the bloodstream, while vaginal dysbiosis enables bacterial infections to reach the uterus [36, 43, 44]. Preeclampsia is one such complication where mothers experience severe high blood pressure and damage to organs like the liver or kidneys during or after pregnancy [45]. A significant cause of birth-related complications, preeclampsia greatly increases maternal, fetal, and infant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Microbiota dysbiosis contributes to preeclampsia through inflammation, immune disruption, and dysfunction of the placenta — an organ that provides nutrients to the fetus from the mother. The convergence of gut and vaginal dysbiosis illustrates how the gut and vaginal microbiomes can have concerted effects on human health, particularly in pregnant women [44].

Moving into the Village: Bacterial Transmission Across Different Delivery Modes

Maternal microbiome interactions between the gut and vagina not only influence pregnancy outcomes but also help determine the microbial communities that are first transmitted to the newborn. The initial colonization of the infant’s gut is crucial for its health and long-term development [46, 47]. As the gut microbiome develops, the infant acquires species that aid in nutrient utilization, vitamin production, and the breakdown of foreign compounds [48, 49]. Postnatally, the bacteria obtained by the infant support the digestion of breast milk, formula, and solid foods, without which infants could not digest food [48, 49]. For instance, Bifidobacterium aids in the processing of breast milk and enables infants to absorb essential nutrients for growth and development [50, 51]. The gut microbiomes of infants delivered vaginally are colonized by maternal vaginal and fecal microbes [52]. Hence, vaginally delivered babies have a high abundance of vaginal microbes like Lactobacillus during the first few days of life [9]. However, infants born via C-section tend to have gut microbiomes that are colonized by maternal skin and oral microbes, along with hospital-acquired bacteria [48, 52, 53]. Consequently, the gut microbiome of babies born via C-section does not mirror the maternal microbiome as closely as the gut microbiomes of vaginally born babies. C-sections can be life-saving interventions in case of pregnancy, labor, or delivery complications. However, the rate of C-section use has increased in recent decades, largely due to an uptick in non-medically suggested C-sections [54, 55, 56]. C-sections disrupt the microbial transmission process from mother to infant, with C-section babies often experiencing a decreased and delayed colonization of Bacteroides, thus reducing the diversity of bacterial composition [9, 47]. Bacteroides, along with Bifidobacterium, are considered health-protective, and the absence of one or the other could lead to adverse health consequences, such as an increased risk of obesity or diabetes [57]. Therefore, high diversity in the gut microbiome serves a protective function and promotes overall health during the early phases of an infant’s life [51].

Village Mentors at Work: Maternal Microbes Guiding Neonatal Neurodevelopment

Health complications during early infant development, such as malnutrition or infection, can have a long-term influence on physiology and behavior in adulthood [48, 58, 59]. Within this framework, the initial microbial colonization of the infant gut plays a crucial role in neural function and brain development [51, 60, 61]. For that reason, disruption of infant gut colonization can affect neonatal neurodevelopment and may even lead to adverse health outcomes later in life [62]. Research on how the maternal microbiome influences development is limited due to the ethics of conducting experiments on infants and pregnant women [63]. Additionally, the relative novelty of gut microbiome research, coupled with a lack of research on women’s health, means that longitudinal studies in humans are scarce [64]. Much of the knowledge in this area is therefore dependent on rodent studies [65]. Despite these limitations, researchers have formulated several hypotheses on how the maternal microbiome may influence neonatal neurodevelopment.

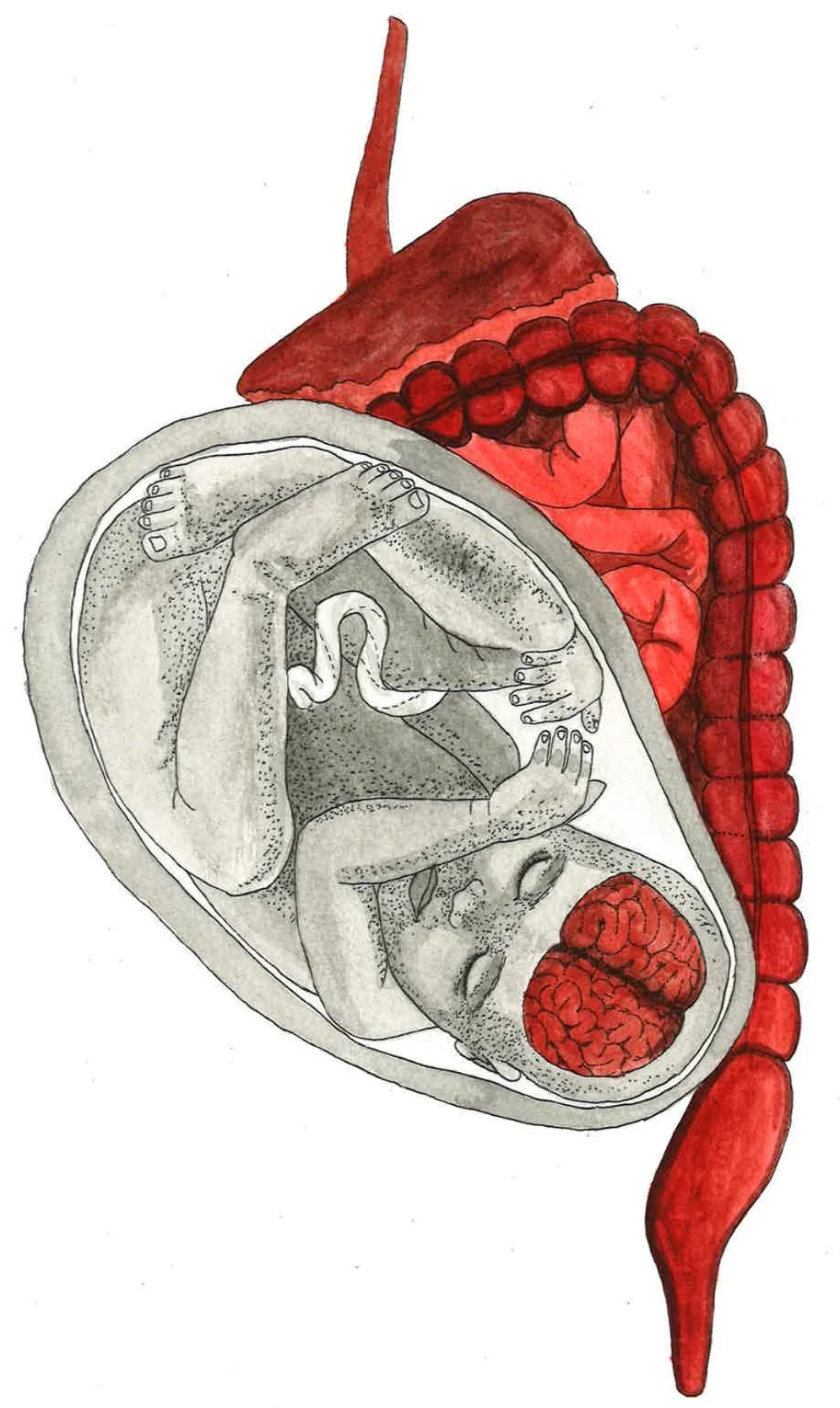

One hypothesis concerns the prenatal period: during this time, metabolites and other substances produced by maternal microbiota may assist in the formation of the fetus’s neural circuits [48]. Neural circuits are pathways of interconnected neurons — cells in the nervous system responsible for transmitting messages throughout the body — and other cells that work together to accomplish specific functions [66, 67]. Microbial metabolites, like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), aid in neural development [68]. After crossing the placenta, SCFAs facilitate the development of neural cells and serve as an energy source for neurons, playing an important role in postnatal neurodevelopment [69, 70, 71]. Moreover, gut microbes have been found to produce enzymes, which are important proteins that transform biological materials into different forms. For example, Lactobacillus reuteri causes an enzyme to change one form of histidine to histamine, a chemical that regulates neurons and behaviors such as wakefulness, attention, and memory [69, 72]. The depletion of the maternal gut microbiome through antibiotic treatment can lead to decreased levels in maternal blood and, in turn, leads to decreased levels in the fetal brain [18, 73]. Collectively, these findings indicate that maternal microbial metabolites act as biochemical mediators between the maternal gut and the developing fetal brain.

A second hypothesis focuses on the postnatal period, proposing that after birth, the microbes an infant acquires from its mother and environment help shape neural circuit formation and regulate molecules involved in brain development [48, 74]. A potential pathway for this mechanism is the gut-brain axis, a system that communicates between the brain and the gut [75, 76]. The vagus nerve extends from the brain to the gut, enabling the relay of signals about the gut’s chemical composition, intestinal conditions, and hormone release [77]. The brain and the gut are like two people talking on the phone, with the vagus nerve as the telephone line that connects them. The vagus nerve promotes growth and reproduction of enteroendocrine cells, which are specialized intestinal cells that can sense microbes and relay information to the brain [78]. SCFAs continue to play a role in neurodevelopment after birth by mediating messages between gut microbiota and the vagus nerve [79]. Therefore, the gut-brain axis represents a direct physiological pathway through which microbiota acquired from the mother may influence neurodevelopment [75]. Both theories are not mutually exclusive and may operate simultaneously, and further research is necessary to clarify exactly how these processes occur [48, 80].

Microbial Mayhem: Maternal Microbiota Dysbiosis Harms Neonatal Neurodevelopment

Knowing that the maternal microbiome impacts neonatal neurodevelopment raises the question of whether maternal dysbiosis can impact the development of neural circuits in infants [79]. Maternal microbial dysbiosis caused by infection or antibiotic use can affect pre- and postnatal development and increase the offspring’s risk of developing neuropsychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorders [81, 82]. For example, getting an infection during pregnancy can trigger the maternal inflammatory response, which is one way fetal and neonatal neurodevelopment is influenced [83, 84]. An inflammatory response in the mother exposes the fetus to an inflammatory environment, since signals can cross the placental barrier and reach the fetus [61]. Inflammatory signals influence fetal brain development by indirectly affecting the function of microglia in the infant [61]. Microglia are immune cells that support the central nervous system (CNS), which encompasses the brain and spinal cord, and influence brain development, maturation, and maintenance [85, 86]. Inflammatory signals cross the fetus’s blood-brain barrier, the highly selective membrane that separates the brain from the rest of the body, and activate microglia, causing neuroinflammation [87]. The maternal inflammatory response can lead to maternal immune activation (MIA), which may disturb signaling between microglia and neurons and contribute to neuroinflammation [83, 84, 88]. MIA is thought to be linked to an offspring’s likelihood of developing neurodevelopmental disorders [85]. MIA also influences brain development at the embryonic stage by impacting the creation and movement of neurons, crucial processes for brain development [89]. There is a decreased production of neurons in the fetal brain, possibly due to cells being forced to exit the cell cycle prematurely. Reduced neuronal production delays neuronal migration, a critical process for CNS development [89, 90].

There is some evidence that suggests MIA can also be induced by maternal gut dysbiosis and lead to behavioral changes associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in offspring [91]. ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder with varying manifestations, but is often characterized by difficulty with social interaction or communication, restricted or repetitive behaviors, and reduced ability to process and respond to external stimuli [61]. Disruption of the gut-brain axis is also associated with ASD-related behaviors [92, 93]. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus support the production and balance of SCFAs that regulate microglia maturation and activation [94]. It is possible that the loss of these microbes through gut dysbiosis may disrupt microglia function and lead to an impaired neuroimmunological response, correlating with an increased risk of developing ASD behaviors. Additionally, altered SCFA levels are thought to underlie some of the neural and behavioral symptoms observed in ASD due to neuroinflammation [91]. Weakening of the gut barrier, due to a condition known as ‘leaky gut,’ or excess intestinal permeability, has also been suggested to increase rates of ASD characteristics — though this research is based on correlations, and is not definitive [93, 95]. Microbial products can leak into circulation and invade the CNS, which may trigger a neuroinflammatory response. Despite these connections, it is difficult to draw any definitive conclusions on whether or not ASD is the cause or a result of a dysbiotic gut microbiome [61].

Using antibiotics during pregnancy can alter the maternal microbiota composition by reducing bacterial diversity [48]. While antibiotics are often used as a preventative and necessary measure against infection, antibiotic overuse can cause maternal dysbiosis and affect the infant’s initial gut colonization [69, 81]. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium produce GABA, a chemical messenger between neurons essential for controlling stress, anxiety, and sleep, as well as regulating gut motility and inflammation [96, 97]. By depleting these beneficial bacteria, antibiotic treatment alters the production of SCFAs and chemical messengers like GABA, which may lead to dysfunction of the gut barrier, blood-brain barrier, and neuroimmune interactions [91, 96, 98]. Overuse of antibiotics may even alter the expression of molecules involved in learning and memory through changes in gut microbiota composition. [99]. For example, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, a protein that promotes brain health, showed altered levels in response to changes in microbial composition caused by antibiotics [100]. Furthermore, exposure to antibiotics can result in delayed maturation of inhibitory neural circuits, or more specifically, parvalbumin-expressing inhibitory interneurons (PV+ INS). PV+ INS are neurons that serve as intermediaries between sensory and motor neurons [101]. PV+ INS mature after birth and are involved in processing external stimuli and feedforward inhibition — a process that acts as a warning system, to dampen a target neuron's response to a messenger [98, 101]. Exposure to antibiotics slows the maturation of PV+ INS, causing physical changes in the brain and impairing sensory perception [102]. Altogether, maternal gut dysbiosis caused by infection or antibiotic use can lead to maternal immune activation that can disturb the brain development process.

Disaster Prevention: How Probiotics Can Protect Maternal and Infant Health

The mother-infant relationship extends beyond genetics and environment to the microbial level, where maternal microbiota play a powerful and lasting role in shaping neonatal neurodevelopment. The microbial link between mother and infant can be leveraged to positively influence health outcomes for both. Pregnant people can be more susceptible to infection, so it is particularly important to maintain maternal health and a balanced microbiome for the sake of both the mother and the infant [103, 104]. Probiotics are live microorganisms that provide health benefits, such as strengthening the immune system or improving digestive health [105, 106]. When administered during pregnancy, probiotics can support the infant microbiome and overall health [105, 107]. Probiotics can also be given directly to infants who experience a disruption in initial gut colonization, though they are not effective in every scenario [108]. More research is needed to determine the exact mechanisms by which maternal microbiota influence neonatal neurodevelopment. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that microbes are essential in shaping the mother-child relationship and human health.

References

Gupta, A., Gupta, R., & Singh, R. L. (2017). Microbes and Environment. In R. L. Singh (Ed.), Principles and Applications of Environmental Biotechnology for a Sustainable Future (pp. 43–84). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1866-4_3

Ogunrinola, G. A., Oyewale, J. O., Oshamika, O. O., & Olasehinde, G. I. (2020). The Human Microbiome and Its Impacts on Health. International Journal of Microbiology, 2020, 8045646. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8045646

Moriel, D. G., Piccioli, D., Raso, M. M., & Pizza, M. (2024). The overlooked bacterial pandemic. Seminars in Immunopathology, 45(4), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-023-00997-1

Dieterich, W., Schink, M., & Zopf, Y. (2018). Microbiota in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Medical Sciences, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci6040116

Khalil, M., Ciaula, A. D., Mahdi, L., Jaber, N., Palo, D. M. D., Graziani, A., Baffy, G., & Portincasa, P. (2024). Unraveling the Role of the Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Diseases. Microorganisms, 12(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12112333

Shabani, M., Ghoshehy, A., Mottaghi, A. M., Chegini, Z., Kerami, A., Shariati, A., & Taati Moghadam, M. (2025). The relationship between gut microbiome and human diseases: Mechanisms, predisposing factors and potential intervention. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1516010

Delaroque, C., & Chassaing, B. (2025). Microbiome in heritage: How maternal microbiome transmission impacts next generation health. Microbiome, 13(1), 196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-025-02186-8

Mady, E. A., Doghish, A. S., El-Dakroury, W. A., Elkhawaga, S. Y., Ismail, A., El-Mahdy, H. A., Elsakka, E. G. E., & El-Husseiny, H. M. (2023). Impact of the mother’s gut microbiota on infant microbiome and brain development. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 150, 105195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105195

Thursby, E., & Juge, N. (2017). Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochemical Journal, 474(11), 1823–1836. https://doi.org/10.1042/BCJ20160510

Ward, J. M., Treuting, P. M., & Washington, M. K. (2021). The Gastrointestinal Tract. In Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice (pp. 259–283). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119624608.ch13

Wiertsema, S. P., Bergenhenegouwen, J. van, Garssen, J., & Knippels, L. M. J. (2021). The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030886

Schmitz, O. J. (2018). Species in ecosystems and all that jazz. PLOS Biology, 16(7), e2006285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2006285

Walsh, J. R., Carpenter, S. R., & Vander Zanden, M. J. (2016). Invasive species triggers a massive loss of ecosystem services through a trophic cascade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(15), 4081–4085. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600366113

Culp, E. J., & Goodman, A. L. (2023). Cross-feeding in the gut microbiome: Ecology and mechanisms. Cell Host & Microbe, 31(4), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2023.03.016

Kumar, S., Mukherjee, R., Gaur, P., Leal, É., Lyu, X., Ahmad, S., Puri, P., Chang, C.-M., Raj, V. S., & Pandey, R. P. (2025). Unveiling roles of beneficial gut bacteria and optimal diets for health. Frontiers in Microbiology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1527755

Zhang, Y.-J., Li, S., Gan, R.-Y., Zhou, T., Xu, D.-P., & Li, H.-B. (2015). Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(4), 7493–7519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16047493

Hou, K., Wu, Z.-X., Chen, X.-Y., Wang, J.-Q., Zhang, D., Xiao, C., Zhu, D., Koya, J. B., Wei, L., Li, J., & Chen, Z.-S. (2022). Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 7(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00974-4

Vaz, S. (2021). Chapter 1—Introduction to organic and inorganic residues in agriculture. In S. Vaz (Ed.), Analysis of Chemical Residues in Agriculture (pp. 1–19). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85208-1.00005-X

Medina, K. L. (2016). Chapter 4—Overview of the immune system. In S. J. Pittock & A. Vincent (Eds.), Autoimmune Neurology (Vol. 133, pp. 61–76). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63432-0.00004-9

Lin, Q., Lin, S., Fan, Z., Liu, J., Ye, D., & Guo, P. (2024). A Review of the Mechanisms of Bacterial Colonization of the Mammal Gut. Microorganisms, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12051026

Zhou, X., Shen, X., Johnson, J. S., Spakowicz, D. J., Agnello, M., Zhou, W., Avina, M., Honkala, A., Chleilat, F., Chen, S. J., Cha, K., Leopold, S., Zhu, C., Chen, L., Lyu, L., Hornburg, D., Wu, S., Zhang, X., Jiang, C., … Snyder, M. P. (2024). Longitudinal profiling of the microbiome at four body sites reveals core stability and individualized dynamics during health and disease. Cell Host & Microbe, 32(4), 506-526.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2024.02.012

DeGruttola, A. K., Low, D., Mizoguchi, A., & Mizoguchi, E. (2016). Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 22(5), 1137–1150. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000750

Dubé-Zinatelli, E., Mayotte, E., Cappelletti, L., & Ismail, N. (2025). Impact of the maternal microbiome on neonatal immune development. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 170, 104542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jri.2025.104542

Soni, J., Sinha, S., & Pandey, R. (2024). Understanding bacterial pathogenicity: A closer look at the journey of harmful microbes. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1370818

Shen, Y., Fan, N., Ma, S., Cheng, X., Yang, X., & Wang, G. (2025). Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, Diseases, Prevention, and Therapy. MedComm, 6(5), e70168. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.70168

Olvera-Rosales, L.-B., Cruz-Guerrero, A.-E., Ramírez-Moreno, E., Quintero-Lira, A., Contreras-López, E., Jaimez-Ordaz, J., Castañeda-Ovando, A., Añorve-Morga, J., … González-Olivares, L.-G. (2021). Impact of the Gut Microbiota Balance on the Health–Disease Relationship: The Importance of Consuming Probiotics and Prebiotics. Foods, 10(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061261

Sehgal, K., & Khanna, S. (2021). Gut microbiome and Clostridioides difficile infection: A closer look at the microscopic interface. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology, 14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756284821994736

Dey, P., & Ray Chaudhuri, S. (2023). The opportunistic nature of gut commensal microbiota. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 49(6), 739–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2022.2133987

Paone, P., & Cani, P. D. (2020). Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut 2020(69), 2232-2243. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322260

Desai, M. S., Seekatz, A. M., Koropatkin, N. M., Kamada, N., Hickey, C. A., Wolter, M., Pudlo, N. A., Kitamoto, S., Terrapon, N., Muller, A., Young, V. B., Henrissat, B., Wilmes, P., Stappenbeck, T. S., Núñez, G., & Martens, E. C. (2016). A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell, 167(5), 1339-1353.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043

Luis, A. S., & Hansson, G. C. (2023). Intestinal mucus and their glycans: A habitat for thriving microbiota. Cell Host & Microbe, 31(7), 1087–1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2023.05.026

Pollet, R. M., Martin, L. M., & Koropatkin, N. M. (2021). TonB-dependent transporters in the Bacteroidetes: Unique domain structures and potential functions. Molecular Microbiology, 115(3), 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/mmi.14683

Chen, X., Lu, Y., Chen, T., & Li, R. (2021). The Female Vaginal Microbiome in Health and Bacterial Vaginosis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.631972

Walker, R. W., Clemente, J. C., Peter, I., & Loos, R. J. F. (2017). The prenatal gut microbiome: Are we colonized with bacteria in utero? Pediatric Obesity, 12(S1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12217

Aldunate, M., Srbinovski, D., Hearps, A. C., Latham, C. F., Ramsland, P. A., Gugasyan, R., Cone, R. A., & Tachedjian, G. (2015). Antimicrobial and immune modulatory effects of lactic acid and short chain fatty acids produced by vaginal microbiota associated with eubiosis and bacterial vaginosis. Frontiers in Physiology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2015.00164

Amabebe, E., & Anumba, D. O. C. (2018). The Vaginal Microenvironment: The Physiologic Role of Lactobacilli. Frontiers in Medicine, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00181

Yu, X., Li, X., & Yang, H. (2024). Unraveling intestinal microbiota’s dominance in polycystic ovary syndrome pathogenesis over vaginal microbiota. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1364097

Saraf, V. S., Sheikh, S. A., Ahmad, A., Gillevet, P. M., Bokhari, H., & Javed, S. (2021). Vaginal microbiome: Normalcy vs dysbiosis. Archives of Microbiology, 203(7), 3793–3802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-021-02414-3

Coudray, M. S., & Madhivanan, P. (2020). Bacterial vaginosis—A brief synopsis of the literature. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 245, 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.12.035

Baud, A., Hillion, K.-H., Plainvert, C., Tessier, V., Tazi, A., Mandelbrot, L., Poyart, C., & Kennedy, S. P. (2023). Microbial diversity in the vaginal microbiota and its link to pregnancy outcomes. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 9061. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36126-z

Shroff, S. (2023). Infectious Vaginitis, Cervicitis, and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Medical Clinics of North America, 107(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2022.10.009

Meštrović, T., Matijašić, M., Perić, M., Paljetak, H. Č., Barešić, A., & Verbanac, D. (2020). The Role of Gut, Vaginal, and Urinary Microbiome in Urinary Tract Infections: From Bench to Bedside. Diagnostics, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010007

Ahmed, U., Fatima, F., & Farooq, H. A. (2025). Microbial dysbiosis and associated disease mechanisms in maternal and child health. Infection and Immunity, 93(8), e00179-25. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00179-25

Torres-Torres, J., Basurto-Serrano, J. A., Camacho-Martinez, Z. A., Guadarrama-Sanchez, F. R., Monroy-Muñoz, I. E., Perez-Duran, J., Solis-Paredes, J. M., … Rojas-Zepeda, L. (2025). Microbiota Dysbiosis: A Key Modulator in Preeclampsia Pathogenesis and Its Therapeutic Potential. Microorganisms, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13020245

Sharma, D. D., Chandresh, N. R., Javed, A., Girgis, P., Zeeshan, M., Fatima, S. S., Arab, T. T., … Mylavarapu, M. (2024). The Management of Preeclampsia: A Comprehensive Review of Current Practices and Future Directions. Cureus, 16. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51512

Tamburini, S., Shen, N., Wu, H. C., & Clemente, J. C. (2016). The microbiome in early life: Implications for health outcomes. Nature Medicine, 22(7), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4142

Pahirah, N., Narkwichean, A., Taweechotipatr, M., Wannaiampikul, S., Duang-Udom, C., & Laosooksathit, W. (2024). Comparison of Gut Microbiomes Between Neonates Born by Cesarean Section and Vaginal Delivery: Prospective Observational Study. BioMed Research International, 2024(1), 8302361. https://doi.org/10.1155/bmri/8302361

Vuong, H. E. (2022). Chapter One—Intersections of the microbiome and early neurodevelopment. In T. R. Sampson (Ed.), Microbiome in Neurological Disease (Vol. 167, pp. 1–23). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2022.06.004

Yao, Y., Cai, X., Ye, Y., Wang, F., Chen, F., & Zheng, C. (2021). The Role of Microbiota in Infant Health: From Early Life to Adulthood. Frontiers in Immunology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.708472

Wu, S., Luo, G., Jiang, F., Jia, W., Li, J., Huang, T., Zhang, X., Mao, Y., Su, S., Han, W., He, F., & Cheng, R. (2025). Early life bifidobacterial mother–infant transmission: Greater contribution from the infant gut to human milk revealed by microbiomic and culture-based methods. mSystems, 10(7), e00480-25. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00480-25

Yang, I., Corwin, E. J., Brennan, P. A., Jordan, S., Murphy, J. R., & Dunlop, A. (2016). The Infant Microbiome: Implications for Infant Health and Neurocognitive Development. Nursing Research, 65(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000133

Zhang, C., Li, L., Jin, B., Xu, X., Zuo, X., Li, Y., & Li, Z. (2021). The Effects of Delivery Mode on the Gut Microbiota and Health: State of Art. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.724449

Mitchell, C. M., Mazzoni, C., Hogstrom, L., Bryant, A., Bergerat, A., Cher, A., Pochan, S., Herman, P., Carrigan, M., Sharp, K., Huttenhower, C., Lander, E. S., Vlamakis, H., Xavier, R. J., & Yassour, M. (2020). Delivery Mode Affects Stability of Early Infant Gut Microbiota. Cell Reports. Medicine, 1(9), 100156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100156

Zhou, L., Qiu, W., Wang, J., Zhao, A., Zhou, C., Sun, T., Xiong, Z., Cao, P., Shen, W., Chen, J., Lai, X., Zhao, L., Wu, Y., Li, M., Qiu, F., Yu, Y., Xu, Z. Z., Zhou, H., Jia, W., … He, Y. (2023). Effects of vaginal microbiota transfer on the neurodevelopment and microbiome of cesarean-born infants: A blinded randomized controlled trial. Cell Host & Microbe, 31(7), 1232-1247.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2023.05.022

Boerma, T., Ronsmans, C., Melesse, D. Y., Barros, A. J. D., Barros, F. C., Juan, L., Moller, A.-B., Say, L., Hosseinpoor, A. R., Yi, M., Neto, D. de L. R., & Temmerman, M. (2018). Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. The Lancet, 392(10155), 1341–1348. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31928-7

Kebede, T. N., Abebe, K. A., Chekol, M. S., Moltot Kitaw, T., Mihret, M. S., Fentie, B. M., Sibhat, Y. A., Tizazu, M. A., Beshah, S. H., & Taye, B. T. (2024). The effect of continuous electronic fetal monitoring on mode of delivery and neonatal outcome among low-risk laboring mothers at Debre Markos comprehensive specialized hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, Volume 5-2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2024.1385343

Stuivenberg, G. A., Burton, J. P., Bron, P. A., & Reid, G. (2022). Why Are Bifidobacteria Important for Infants? Microorganisms, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020278

Gur, T. L., Worly, B. L., & Bailey, M. T. (2015). Stress and the commensal microbiota: Importance in parturition and infant neurodevelopment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00005

Guo, J., Wu, J., He, Q., Zhang, M., Li, H., & Liu, Y. (2022). The Potential Role of PPARs in the Fetal Origins of Adult Disease. Cells, 11(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11213474

Vaher, K., Bogaert, D., Richardson, H., & Boardman, J. P. (2022). Microbiome-gut-brain axis in brain development, cognition and behavior during infancy and early childhood. Developmental Review, 66, 101038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2022.101038

Mavel, S., Pellé, L., & Andres, C. R. (2025). Impact of maternal microbiota imbalance during pregnancy on fetal cerebral neurodevelopment: Is there a link to certain autistic disorders? Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, 48, 101074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2025.101074

Ronde, E., Alkema, M., Dierikx, T., Schoenmakers, S., Belzer, C., & de Meij, T. (2025). The influence of maternal gut and vaginal microbiota on gastrointestinal colonization of neonates born vaginally and per caesarean section. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 25(1), 254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07358-w

McKiever, M., Frey, H., & Costantine, M. M. (2020). Challenges in conducting clinical research studies in pregnant women. Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics, 47(4), 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-020-09687-z

Siddiqui, R., Makhlouf, Z., Alharbi, A. M., Alfahemi, H., & Khan, N. A. (2022). The Gut Microbiome and Female Health. Biology, 11(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11111683

Singh, G., Brass, A., Cruickshank, S. M., & Knight, C. G. (2021). Cage and maternal effects on the bacterial communities of the murine gut. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 9841. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89185-5

Holt, C. E., Martin, K. C., & Schuman, E. M. (2019). Local translation in neurons: Visualization and function. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 26(7), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-019-0263-5

Lerner, T. N., Ye, L., & Deisseroth, K. (2016). Communication in Neural Circuits: Tools, Opportunities, and Challenges. Cell, 164(6), 1136–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.027

Liufu, S., Xu, X., Lan, Q., Chen, B., Wang, K., Xiao, L., Chen, W., Wen, W., Liu, C., Yi, L., Liu, J., Fu, X., Ma, H. (2025). Temporal Dynamics of Fecal Microbiome and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Sows from Early Pregnancy to Weaning. Animals, 15(15). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152209

Jašarević, E., Rodgers, A. B., & Bale, T. L. (2015). A novel role for maternal stress and microbial transmission in early life programming and neurodevelopment. Neurobiology of Stress, 1, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.10.005

He, Y., Xie, K., Yang, K., Wang, N., & Zhang, L. (2025). Unraveling the Interplay Between Metabolism and Neurodevelopment in Health and Disease. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 31(5), e70427. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.70427

Kimura, I., Miyamoto, J., Ohue-Kitano, R., Watanabe, K., Yamada, T., Onuki, M., Aoki, R., Isobe, Y., Kashihara, D., Inoue, D., Inaba, A., Takamura, Y., Taira, S., Kumaki, S., Watanabe, M., Ito, M., Nakagawa, F., Irie, J., Kakuta, H., … Hase, K. (2020). Maternal gut microbiota in pregnancy influences offspring metabolic phenotype in mice. Science, 367(6481), eaaw8429. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw8429

Carthy, E., & Ellender, T. (2021). Histamine, Neuroinflammation and Neurodevelopment: A Review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.680214

Vuong, H. E., Pronovost, G. N., Williams, D. W., Coley, E. J. L., Siegler, E. L., Qiu, A., Kazantsev, M., Wilson, C. J., Rendon, T., & Hsiao, E. Y. (2020). The maternal microbiome modulates fetal neurodevelopment in mice. Nature, 586(7828), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2745-3

Tian, M., Li, Q., Zheng, T., Yang, S., Chen, F., Guan, W., & Zhang, S. (2023). Maternal microbe-specific modulation of the offspring microbiome and development during pregnancy and lactation. Gut Microbes, 15(1), 2206505. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2023.2206505

Gars, A., Ronczkowski, N. M., Chassaing, B., Castillo-Ruiz, A., & Forger, N. G. (2021). First Encounters: Effects of the Microbiota on Neonatal Brain Development. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2021.682505

Muhammad, F., Fan, B., Wang, R., Ren, J., Jia, S., Wang, L., Chen, Z., & Liu, X.-A. (2022). The Molecular Gut-Brain Axis in Early Brain Development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(23). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232315389

Yu, C. D., Xu, Q. J., & Chang, R. B. (2020). Vagal sensory neurons and gut-brain signaling. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 62, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2020.03.006

Grundeken, E., & El Aidy, S. (2025). Enteroendocrine cells: The gatekeepers of microbiome-gut-brain communication. Npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 11(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00810-x

Frerichs, N. M., de Meij, T. G. J., & Niemarkt, H. J. (2024). Microbiome and its impact on fetal and neonatal brain development: Current opinion in pediatrics. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 27(3), 297. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000001028

Jašarević, E., & Bale, T. L. (2019). Prenatal and postnatal contributions of the maternal microbiome on offspring programming. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 55, 100797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100797

Deady, C., FitzGerald, J., Kara, N., Mazzocchi, M., O’Mahony, A., Ionescu, M. I., Shanahan, R., Kelly, S., Crispie, F., Cotter, P. D., McCarthy, F. P., McCarthy, C., O’Keeffe, G. W., & O’Mahony, S. M. (2025). Maternal immune activation and antibiotics affect offspring neurodevelopment, behaviour, and microbiome. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, 48, 101065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2025.101065

Hudobenko, J., Di Gesù, C. M., Mooz, P. R., Petrosino, J., Putluri, N., Ganesh, B. P., Rebeles, K., Blixt, F. W., Venna, V. R., & McCullough, L. D. (2025). Maternal dysbiosis produces long-lasting behavioral changes in offspring. Molecular Psychiatry, 30(5), 1847–1858. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02794-0

O’Connor, T. G., & Ciesla, A. A. (2022). Maternal Immune Activation Hypotheses for Human Neurodevelopment: Some Outstanding Questions. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 7(5), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2021.10.006

Liu, K., Huang, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhao, Y., & Kong, X. (2023). The role of maternal immune activation in immunological and neurological pathogenesis of autism. Journal of Neurorestoratology, 11(1), 100030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnrt.2022.100030

Zawadzka, A., Cieślik, M., Adamczyk, A., Zawadzka, A., Cieślik, M., & Adamczyk, A. (2021). The Role of Maternal Immune Activation in the Pathogenesis of Autism: A Review of the Evidence, Proposed Mechanisms and Implications for Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111516

Dromel, P. C. (2024). Chapter 5—Drug delivery for central nervous system injury. In D. Singh, P. C. Dromel, & D. J. Thomas (Eds.), Biomaterials and Stem Cell Therapies for Biomedical Applications (pp. 95–124). Woodhead Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-19085-8.00005-9

Alahmari, A. (2021). Blood-Brain Barrier Overview: Structural and Functional Correlation. Neural Plasticity, 2021(1), 6564585. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6564585

Shimamura, T., Kitashiba, M., Nishizawa, K., & Hattori, Y. (2025). Physiological roles of embryonic microglia and their perturbation by maternal inflammation. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2025.1552241

McEwan, F., Glazier, J. D., & Hager, R. (2023). The impact of maternal immune activation on embryonic brain development. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1146710. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1146710

Rahimi-Balaei, M., Bergen, H., Kong, J., & Marzban, H. (2018). Neuronal Migration During Development of the Cerebellum. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2018.00484

Suprunowicz, M., Tomaszek, N., Urbaniak, A., Zackiewicz, K., Modzelewski, S., & Waszkiewicz, N. (2024). Between Dysbiosis, Maternal Immune Activation and Autism: Is There a Common Pathway? Nutrients, 16(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040549

Morton, J. T., Jin, D.-M., Mills, R. H., Shao, Y., Rahman, G., McDonald, D., Zhu, Q., Balaban, M., Jiang, Y., Cantrell, K., Gonzalez, A., Carmel, J., Frankiensztajn, L. M., Martin-Brevet, S., Berding, K., Needham, B. D., Zurita, M. F., David, M., Averina, O. V., … Taroncher-Oldenburg, G. (2023). Multi-level analysis of the gut–brain axis shows autism spectrum disorder-associated molecular and microbial profiles. Nature Neuroscience, 26(7), 1208–1217. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01361-0

Gwak, M.-G., & Chang, S.-Y. (2021). Gut-Brain Connection: Microbiome, Gut Barrier, and Environmental Sensors. Immune Network, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.4110/in.2021.21.e20

Erny, D., Hrabě de Angelis, A. L., Jaitin, D., Wieghofer, P., Staszewski, O., David, E., Keren-Shaul, H., Mahlakoiv, T., Jakobshagen, K., Buch, T., Schwierzeck, V., Utermöhlen, O., Chun, E., Garrett, W. S., McCoy, K. D., Diefenbach, A., Staeheli, P., Stecher, B., Amit, I., & Prinz, M. (2015). Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nature Neuroscience, 18(7), 965–977. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4030

Di Vincenzo, F., Del Gaudio, A., Petito, V., Lopetuso, L. R., & Scaldaferri, F. (2024). Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 19(2), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-023-03374-w

Auteri, M., Zizzo, M. G., & Serio, R. (2015). GABA and GABA receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: From motility to inflammation. Pharmacological Research, 93, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2014.12.001

Braga, J. D., Thongngam, M., & Kumrungsee, T. (2024). Gamma-aminobutyric acid as a potential postbiotic mediator in the gut–brain axis. Npj Science of Food, 8(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00253-2

Diamanti, T., Prete, R., Battista, N., Corsetti, A., & Jaco, A. D. (2022). Exposure to Antibiotics and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Could Probiotics Modulate the Gut–Brain Axis? Antibiotics, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11121767

Fishbein, S. R. S., Mahmud, B., & Dantas, G. (2023). Antibiotic perturbations to the gut microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 21(12), 772–788. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00933-y

Bistoletti, M., Caputi, V., Baranzini, N., Marchesi, N., Filpa, V., Marsilio, I., Cerantola, S., Terova, G., Baj, A., Grimaldi, A., Pascale, A., Frigo, G., Crema, F., Giron, M. C., & Giaroni, C. (2019). Antibiotic treatment-induced dysbiosis differently affects BDNF and TrkB expression in the brain and in the gut of juvenile mice. PLOS ONE, 14(2), e0212856. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212856

Rupert, D. D., & Shea, S. D. (2022). Parvalbumin-Positive Interneurons Regulate Cortical Sensory Plasticity in Adulthood and Development Through Shared Mechanisms. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2022.886629

Perna, J., Lu, J., Mullen, B., Liu, T., Tjia, M., Weiser, S., Ackman, J., & Zuo, Y. (2021). Perinatal Penicillin Exposure Affects Cortical Development and Sensory Processing. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2021.704219

Abu-Raya, B., Michalski, C., Sadarangani, M., & Lavoie, P. M. (2020). Maternal Immunological Adaptation During Normal Pregnancy. Frontiers in Immunology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.575197

Edwards, S. M., Cunningham, S. A., Dunlop, A. L., & Corwin, E. J. (2017). The Maternal Gut Microbiome During Pregnancy. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 42(6), 310. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000372

Cuinat, C., Stinson, S. E., Ward, W. E., & Comelli, E. M. (2022a). Maternal Intake of Probiotics to Program Offspring Health. Current Nutrition Reports, 11(4), 537–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-022-00429-w

Bhutada, S., Samadhan, D., Hassan, Z., & Kovaleva, E. G. (2025). A comprehensive review of probiotics and human health-current prospective and applications. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1487641

Meng, L., Fan, G., Xie, H., Tye, K. D., Xia, L., Luo, H., Tang, X., Huang, T., Lin, J., Ma, G., Xiao, X., & Li, Z. (2025). Maternal–to–neonatal microbial transmission and impact of prenatal probiotics on neonatal gut development. Journal of Translational Medicine, 23(1), 1198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-07293-6

Abu, Y., & Roy, S. (2025). Intestinal dysbiosis during pregnancy and microbiota-associated impairments in offspring. Frontiers in Microbiomes, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/frmbi.2025.1548650

Lu, X., Shi, Z., Jiang, L., & Zhang, S. (2024). Maternal gut microbiota in the health of mothers and offspring: From the perspective of immunology. Frontiers in Immunology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1362784