From Dean's List to Drained List: The Brain Science of Burnout

Joseph Lippman

Racine Rieke

When you picture somebody burning the midnight oil, what comes to mind? An exhausted college student? A nurse during the COVID-19 pandemic, overworked and underappreciated? Chances are, if you have ever overexerted yourself for a period, you are probably familiar with the feeling of burnout. Burnout is commonly thought of as psychological — a way to describe extreme mental exhaustion from being overly stressed [1, 2]. Prolonged exposure to stress, known as chronic stress, can result in feeling burnt out and affects much more than simply our mental state [1, 3]. The impacts of this exhaustion extend to physical ailments such as high blood pressure and obesity [4, 5, 6]. It is vital to understand how burnout affects the mind and body in order to combat its debilitating effects, especially for those who work in consistently high-stress environments.

Burning Low: The Perils of Overcommitment

Imagine a student who is nervous about their upcoming midterm exam. The content feels difficult to understand, they have little time to study, and the exam accounts for a massive percentage of their grade. Needless to say, the student is experiencing a good amount of stress. Stress is a physiological and psychological response that is prompted by a perceived threat, causing worry and increased focus on a given task [7, 8, 9]. While it has an unpleasant reputation, stress in moderation allows us to function efficiently [10, 11]. For example, stress will compel the student to manage their time and focus on studying for their midterm [12, 13, 14]. Studying for a midterm is an example of an acute stress response, characterized by short bursts of stress that allow the individual to push past the stressor [10, 12, 14]. Healthy and unhealthy amounts of stress are best measured by utilizing a principle called the Yerkes-Dodson law, which stipulates that a moderate amount of stress is ideal for optimal performance [15, 16]. This principle suggests that too little stress can lead to insufficient motivation, while excessive stress can lead to anxiety and a decline in performance [15, 16].

Chronic stress occurs when the body is overloaded with a repeated or constant stress response [17, 18, 19]. A student may be struggling with chronic stress if they are constantly worrying about their exam to the extent that they are unable to focus or commit to productive studying [20, 21]. Individuals working under excessive workloads and high emotional demands, such as healthcare workers in hospital settings, commonly experience chronic stress [3, 22, 23]. Chronic stress overwhelms the body’s response to acute stressors, interrupting the process of returning to a resting state and prolonging the symptoms of stress [17, 18]. For instance, if the student experiences chronic stress from being spread too thin with commitments and is unable to study efficiently, their chronic stress can result in burnout [3, 23]. In burnout, an individual might feel severe emotional exhaustion, lack of personal achievement, and general cynicism [3, 23, 24]. Historically, the association of burnout with stressful work environments has led many to believe that burnout is simply psychological [1, 2, 14]. This is, however, an incorrect assumption, as burnout is also physiological [14, 25, 26]. In the case of burnout, the physiological symptoms of the typical stress response, such as increased blood pressure and exhaustion, become prolonged and can potentially lead to harmful long-term health consequences [14, 25, 26]. Therefore, it is important to understand the mechanism of the typical stress response and what changes when it becomes chronic [26, 27].

Homework. Panic. Anxiety: The HPA Axis

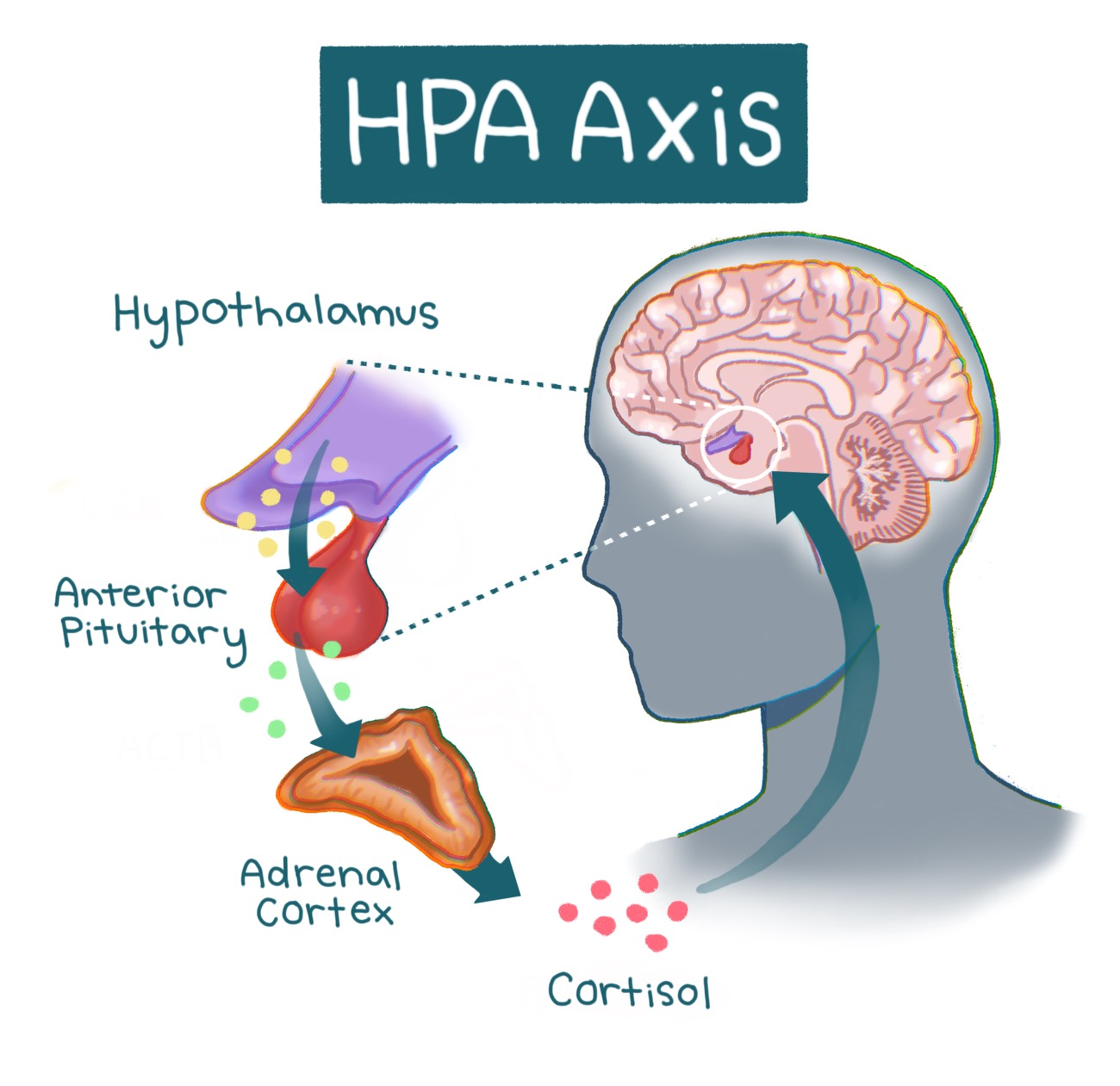

Stress responses are mediated by a pathway in our brain and body known as the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis [11, 28]. At the onset of a stressful event, the hypothalamus is activated [10, 11]. The hypothalamus is a structure in the brain responsible for multiple regulatory functions and links the brain’s emotional centers with the major structures involved in the stress response [28, 29]. Activation of the hypothalamus triggers a cascade of hormones — chemical messengers that mobilize the energy and resources needed for the body to overcome a stressor [11, 28]. The cascade is similar to a relay race, with different hormones acting as runners that pass the ‘stress response’ baton. In the first leg of the race, hormones carry the baton from the hypothalamus to the brain structure that acts as the hormonal control center called the pituitary gland, which releases hormones that control metabolism, blood pressure, and other physiological responses [11, 28, 30]. The second runner — the next set of hormones — carries the baton to the adrenal gland, which produces one particularly important hormone released in this process: cortisol, commonly known as the ‘stress hormone’ [10, 31]. Cortisol is also involved in immune function, as well as helping to regulate metabolism and blood pressure [10, 31]. Following its release, cortisol prompts the hypothalamus to cease the cortisol-producing hormone cascade [11, 32]. Similarly, once the relay runners cross the finish line, the race is over. The inhibition of the hormone cascade restores the body to a neutral state [10, 11]. Think of the HPA axis as a thermostat that adjusts to changing temperatures. When the thermostat senses that the temperature is warmer than the set temperature — such as when cortisol levels are elevated — the thermostat will turn off the heat. Once cortisol signals to the hypothalamus to stop sending signals to the pituitary gland, overall cortisol production will be reduced [10, 11]. The restoration of the body to a neutral state is key in acute stress responses, as it allows a person to focus on a stressor or task for the duration of the response and then return to regular functioning [10, 33]. When cortisol is regulated correctly, the HPA axis maintains the ability to utilize stress constructively [10, 11]. However, as most college students will report, stress does not always feel healthy [33, 34].

During states of chronic stress, prolonged activation of the HPA axis leads to hypercortisolism, a condition characterized by excess cortisol production [11, 26, 35]. In the early stages of burnout, symptoms have been heavily associated with hypercortisolism — excess cortisol release — highlighting a link between overactivation of the HPA axis and burnout [26, 35, 36]. With that said, severe burnout has also paradoxically been associated with hypocortisolism, a condition characterized by reduced cortisol release from the HPA axis [36, 37]. Hypercortisolism eventually transforms into hypocortisolism as the body stops being able to produce cortisol efficiently in response to constant stress [37, 38, 39]. After experiencing heightened levels of cortisol, individuals may experience a blunted stress response caused by hypocortisolism that can manifest as negative feelings, depressed mood, and reduced task-related motivation [4, 5, 40]. For a burnt-out student, a blunted stress response during burnout might look like having significantly lower motivation to study or perform well and believing they will get a bad grade regardless of their efforts.

Mind-Body Meltdown: The Consequences of Burnout

While the physiological ramifications of hypocortisolism remain understudied, hypercortisolism has been connected to negative health outcomes such as altered cardiovascular function and impaired stress response [6, 41, 42]. During a stress response, hypercortisolism can additionally lead to the dysregulation of metabolic processes, wherein the body struggles to process carbohydrates, fats, and sugars [6, 43, 44]. Excess levels of cortisol from the chronic stress response can make it harder for the body to manage blood sugar, sometimes leading to hyperglycemia, or an excess of sugar in the blood [45, 46, 47]. Chronic stress also activates the body’s immune system, releasing inflammatory molecules called cytokines in order to attempt to attack the stressor and stop the endless stress response cycle [48, 51]. While inflammation is helpful in short bursts, persistent inflammation, caused by the sustained activation of the HPA axis, can disrupt metabolism, making it harder to control blood sugar and contributing to weight gain as well as other health risks [47, 49, 50]. Usually, when blood sugar rises, the body signals the pancreas to release insulin, the hormone that allows cells to absorb energy from sugar [52]. Insulin, however, becomes less effective during chronic inflammation due to the cytokines disrupting the insulin signaling pathway [47]. When cells cannot properly take in sugar, it remains in the bloodstream, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes and other metabolic problems [53, 54, 55]. In this way, chronic stress can create a cycle where elevated cortisol and inflammation interfere with the body’s ability to handle sugar and fat, putting long-term health at risk [56, 57]. There are often physiological consequences to psychological processes, such as stress. The HPA axis is a significant example of that brain-body connection [58, 59]. For instance, people with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder experience more physical health issues than the general population [60, 61]. These disorders are all associated with chronically high levels of psychological distress, similar to burnout, which may explain the equivalent health risks [60, 62, 63]. Long-term physiological changes, such as increased inflammation due to chronic stress, can in turn result in the deterioration of tissue in the nervous system [11, 64]. Psychological symptoms of burnout such as cynicism and emotional exhaustion are also coupled with structural changes in the brain, specifically in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), which is involved in regulating stressors [24, 65, 66]. Shrinkage of the vmPFC has been linked to dysregulated HPA axis responsivity and it is possible that this impairment could be due to burnout [65, 66, 67]. Furthermore, burnout may lead to more serious physical conditions culminating in increased mortality below age 45 [85, 86].

Chill Out Before You Burn Out: Preventing Chronic Stress

Burnout, as well as hypercortisolism, often accompanies symptoms such as higher levels of depression, lack of satisfaction with job performance, and substantially altered HPA axis activity [10, 68, 69]. At a societal level, burnout has been concerningly correlated with decreased job performance in critical professions such as nursing, causing a lower quality of patient care [70, 71]. Similar to nurses, other medical professionals are at high risk for burnout due to their high-stakes work environment, which should be reason enough to sound the alarm for access to reliable burnout prevention [69, 72]. Knowing that burnout can be detrimental to long-term psychological and physical well-being, the logical next step is to investigate the ways that burnout could be prevented or mitigated. Physical exercise, including yoga as well as aerobic and strength exercises, has been shown to reduce burnout symptoms and overall stress [73, 74]. Physical exercise can reduce stress via increased production of serotonin — a hormone involved in both emotional regulation and cognitive function [73, 75]. Interestingly, mindfulness-based practices do not show a decrease in burnout, but they do seem to alleviate symptoms such as anxiety and poor mood [76, 77, 78]. If a stressed student is feeling burned out after their midterm and tries to help themselves by engaging in a mindfulness-based practice like meditation, they might feel a short-term reduction in anxiety and be in a better mood. However, while these short-term effects may be achieved, meditative practices are unlikely to improve cortisol levels in the body and will not change how burned-out the student actually feels [74, 78]. It is critical to consider the effects that burnout has on society to prioritize reliable burnout prevention and reduction strategies. As established, healthcare workers are particularly vulnerable to burnout due to their intense work schedules and the stakes of their jobs [69, 70]. Strategies that focus on reducing burnout in a particular individual include reducing monotony in the workday by varying everyday responsibilities as well as receiving guidance from peers and counselors to mediate the effects of burnout before they escalate [79, 80, 81]. On a larger scale, those working high-demand jobs, like doctors, benefitted greatly from structural and policy change such as the alteration of work schedules for more reasonable hours, and the introduction of medical scribes [71, 82, 83]. Structural changes in the healthcare system are needed to reduce physician burnout, an issue that is affecting quality of healthcare [70, 71, 82].

Weathering the Storm: Keeping Stress at Bay

Given the prevalence of burnout today, understanding the complex effects of burnout and chronic stress on the body is profoundly important [69, 70]. More than half of US physicians are now experiencing professional burnout [84]. High-risk populations, like healthcare professionals, require reliable ways to prevent and reduce burnout symptoms to improve both their health and their service to patients [69, 70]. Investigations of burnout prevention strategies have proven that not only is individual treatment required in the form of physical stress-busters, but importantly, that large-scale change is needed to refine the systems that generate lasting burnout for healthcare workers [87, 88]. Burnout has been proven to be a physiological phenomenon in addition to a psychological one, as evidenced by the effects of chronic stress on both the brain and body [4, 5, 6]. With the knowledge that acute stress is a normal and helpful response, we should strive to embrace stress in a healthy manner while also being mindful of the possible consequences of chronic stress [10, 12, 14].

References

de Vente, W., van Amsterdam, J. G., Olff, M., Kamphuis, J. H., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2015). Burnout is associated with reduced parasympathetic activity and reduced HPA axis responsiveness, predominantly in males. BioMed Research International, 1–13. doi:10.1155/2015/431725

Pihlaja, M., Tuominen, P. P., Peräkylä, J., & Hartikainen, K. M. (2022). Occupational burnout is linked with inefficient executive functioning, elevated average heart rate, and decreased physical activity in daily life - Initial evidence from teaching professionals. Brain Sciences, 12(12), 1723. doi:10.3390/brainsci12121723

Doulougeri, K., Georganta, K., & Montgomery, A. (2016). “Diagnosing” burnout among healthcare professionals: Can we find consensus? Cogent Medicine, 3(1). doi:10.1080/2331205X.2016.1237605

Carroll, D., Ginty, A. T., Whittaker, A. C., Lovallo, W. R., & de Rooij, S. R. (2017). The behavioural, cognitive, and neural corollaries of blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 77, 74–86. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.025

Chen, C., Xiong, B., Tan, W., Tian, Y., Zhang, S., Wu, J., Song, P., & Qin, S. (2025). Setting the tone for the day: Cortisol awakening response proactively modulates fronto-limbic circuitry for emotion processing. NeuroImage, 315, 121251. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2025.121251

Li, D., El Kawkgi, O. M., Henriquez, A. F., & Bancos, I. (2020). Cardiovascular risk and mortality in patients with active and treated hypercortisolism. Gland Surgery, 9(1), 43–58. doi:10.21037/gs.2019.11.03

Laferton, J. A. C., Bartsch, L. M., Möschinger, T., Baldelli, L., Frick, S., Breitenstein, C. J., Züger, R., Annen, H., & Fischer, S. (2023). Effects of stress beliefs on the emotional and biological response to acute psychosocial stress in Healthy Men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 152, 106091. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2023.106091

Rojas-Thomas, F., Artigas, C., Wainstein, G., Morales, J.-P., Arriagada, M., Soto, D., Dagnino-Subiabre, A., Silva, J., & Lopez, V. (2023). Impact of acute psychosocial stress on attentional control in humans. A study of evoked potentials and pupillary response. Neurobiology of Stress, 25, 100551. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2023.100551

James, K. A., Stromin, J. I., Steenkamp, N., & Combrinck, M. I. (2023). Understanding the relationships between physiological and psychosocial stress, cortisol and cognition. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1085950

Isakovic, B., Bertoldi, B., Tuvblad, C., Cucurachi, S., Raine, A., Baker, L., Ling, S., & Evans, B. E. (2023). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responsivity during adolescence in relation to psychopathic personality traits later in life. Acta Psychologica, 241, 104055. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.104055

P, S., & Vellapandian, C. (2024). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis: Unveiling the potential mechanisms involved in stress-induced alzheimer’s disease and depression. Cureus. doi:10.7759/cureus.67595

Voulgaropoulou, S. D., Fauzani, F., Pfirrmann, J., Vingerhoets, C., van Amelsvoort, T., & Hernaus, D. (2022). Asymmetric effects of acute stress on cost and benefit learning. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 138, 105646. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105646

Pluut, H., Curșeu, P. L., & Fodor, O. C. (2022). Development and validation of a short measure of emotional, physical, and behavioral markers of eustress and distress (MEDS). Healthcare, 10(2), 339. doi:10.3390/healthcare10020339

Ahmed, F., Dubey, D. K., Garg, R., & Srivastava, R. (2023). Effects of examination-induced stress on memory and blood pressure. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 12(11), 2757–2762. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_925_23

McGinley, M. J., Vinck, M., Reimer, J., Batista-Brito, R., Zagha, E., Cadwell, C. R., Tolias, A. S., Cardin, J. A., & McCormick, D. A. (2015). Waking state: Rapid variations modulate neural and behavioral responses. Neuron, 87(6), 1143–1161. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.012

Bray, E. E., MacLean, E. L., & Hare, B. A. (2015). Increasing arousal enhances inhibitory control in calm but not excitable dogs. Animal Cognition, 18(6), 1317–1329. doi:10.1007/s10071-015-0901-1

Mariotti, A. (2015). The effects of chronic stress on health: New insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain–body communication. Future Science OA, 1(3). doi:10.4155/fso.15.21

khan, A., Song, M., & Dong, Z. (2025). Chronic stress: A fourth etiology in tumorigenesis? Molecular Cancer, 24(1). doi:10.1186/s12943-025-02402-x

Atrooz, F., Alkadhi, K. A., & Salim, S. (2021). Understanding stress: Insights from rodent models. Current Research in Neurobiology, 2, 100013. doi:10.1016/j.crneur.2021.100013

Zeeman, J. M., Anderson, E. B., Matt, I. C., Jarstfer, M. B., & Harris, S. C. (2025). Assessing factors that influence graduate student burnout in health professions education and identifying recommendations to support their well-being. PLOS ONE, 20(4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0319857

Szwamel, K., Kowalska, W., Mazur, E., Janus, A., Bonikowska, I., & Jasik-Pyzdrowska, J. (2025). Determinants of burnout syndrome among undergraduate nursing students in poland: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 25(1). doi:10.1186/s12909-025-06777-9

Brindley, P. G., Olusanya, S., Wong, A., Crowe, L., & Hawryluck, L. (2019). Psychological ‘burnout’ in healthcare professionals: Updating our understanding, and not making it worse. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 20(4), 358–362. doi:10.1177/1751143719842794

West, C. P., Dyrbye, L. N., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2018). Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. Journal of Internal Medicine, 283(6), 516–529. doi:10.1111/joim.12752

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. doi:10.1002/wps.20311

Andelic, N., Allan, J., Bender, K. A., Powell, D., & Theodossiou, I. (2023). Stress in performance-related pay: The effect of payment contracts and social-evaluative threat. Stress, 26(1). doi:10.1080/10253890.2023.2283435

Ibar, C., Fortuna, F., Gonzalez, D., Jamardo, J., Jacobsen, D., Pugliese, L., Giraudo, L., Ceres, V., Mendoza, C., Repetto, E. M., Reboredo, G., Iglesias, S., Azzara, S., Berg, G., Zopatti, D., & Fabre, B. (2021). Evaluation of stress, burnout and hair cortisol levels in health workers at a university hospital during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 128, 105213. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105213

Rohleder, N. (2019). Stress and inflammation – The need to address the gap in the transition between acute and chronic stress effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 105, 164–171. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.02.021

Herman, J. P., McKlveen, J. M., Ghosal, S., Kopp, B., Wulsin, A., Makinson, R., Scheimann, J., & Myers, B. (2016). Regulation of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenocortical stress response. Comprehensive Physiology, 6(2), 603–621. doi:10.1002/j.2040-4603.2016.tb00694.x

Schindler, S., Schmidt, L., Stroske, M., Storch, M., Anwander, A., Trampel, R., Strauß, M., Hegerl, U., Geyer, S., & Schönknecht, P. (2018). Hypothalamus enlargement in mood disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 139(1), 56–67. doi:10.1111/acps.12958

Al salman, J. M., Al Agha, R. A., & Helmy, M. (2017). Pituitary abscess. BMJ Case Reports. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-217912

Johnson, K., Peterson, J., Kopper, J., & Dembek, K. (2023). The hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis response to ovine corticotropin‐releasing‐hormone stimulation tests in healthy and hospitalized foals. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 37(1), 292–301. doi:10.1111/jvim.16604

Gjerstad, J. K., Lightman, S. L., & Spiga, F. (2018). Role of glucocorticoid negative feedback in the regulation of HPA axis pulsatility. Stress, 21(5), 403–416. doi:10.1080/10253890.2018.1470238

Wadsworth, M. E., Broderick, A. V., Loughlin‐Presnal, J. E., Bendezu, J. J., Joos, C. M., Ahlkvist, J. A., Perzow, S. E., & McDonald, A. (2019). Co‐activation of SAM and HPA responses to acute stress: A review of the literature and test of differential associations with preadolescents’ internalizing and externalizing. Developmental Psychobiology, 61(7), 1079–1093. doi:10.1002/dev.21866

Barbayannis, G., Bandari, M., Zheng, X., Baquerizo, H., Pecor, K. W., & Ming, X. (2022). Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: Correlations, affected groups, and covid-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.886344

Penz, M., Stalder, T., Miller, R., Ludwig, V. M., Kanthak, M. K., & Kirschbaum, C. (2018). Hair cortisol as a biological marker for burnout symptomatology. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 87, 218–221. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.07.485

Pilger, A., Haslacher, H., Meyer, B. M., Lackner, A., Nassan-Agha, S., Nistler, S., Stangelmaier, C., Endler, G., Mikulits, A., Priemer, I., Ratzinger, F., Ponocny-Seliger, E., Wohlschläger-Krenn, E., Teufelhart, M., Täuber, H., Scherzer, T. M., Perkmann, T., Jordakieva, G., Pezawas, L., & Winker, R. (2018). Midday and nadir salivary cortisol appear superior to cortisol awakening response in burnout assessment and monitoring. Scientific Reports, 8(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-27386-1

Penz, M., Siegrist, J., Wekenborg, M. K., Rothe, N., Walther, A., & Kirschbaum, C. (2019). Effort-reward imbalance at work is associated with hair cortisol concentrations: Prospective evidence from the dresden burnout study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 109, 104399. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104399

Rohleder, N. (2018). Burnout, hair cortisol, and timing: Hyper- or hypocortisolism? Psychoneuroendocrinology, 87, 215–217. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.10.008

Kaltenegger, H. C., Marques, M. D., Becker, L., Rohleder, N., Nowak, D., Wright, B. J., & Weigl, M. (2024). Prospective associations of technostress at work, burnout symptoms, hair cortisol, and chronic low-grade inflammation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 117, 320–329. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2024.01.222

Counts, C. J., Ginty, A. T., Larsen, J. M., Kampf, T. D., & John-Henderson, N. A. (2022). Childhood trauma and cortisol reactivity: An investigation of the role of task appraisals. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.803339

Wekenborg, M. K., von Dawans, B., Hill, L. K., Thayer, J. F., Penz, M., & Kirschbaum, C. (2019). Examining reactivity patterns in burnout and other indicators of chronic stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 106, 195–205. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.04.002

Sahiti, F., Detomas, M., Cejka, V., Hoffmann, K., Gelbrich, G., Frantz, S., Kroiss, M., Heuschmann, P. U., Hahner, S., Fassnacht, M., Deutschbein, T., Störk, S., & Morbach, C. (2025). The impact of hypercortisolism beyond metabolic syndrome on left ventricular performance: A myocardial work analysis. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 24(1). doi:10.1186/s12933-025-02680-1

Crawford, A. A., Soderberg, S., Kirschbaum, C., Murphy, L., Eliasson, M., Ebrahim, S., Davey Smith, G., Olsson, T., Sattar, N., Lawlor, D. A., Timpson, N. J., Reynolds, R. M., & Walker, B. R. (2019). Morning plasma cortisol as a cardiovascular risk factor: Findings from prospective cohort and mendelian randomization studies. European Journal of Endocrinology, 181(4), 429–438. doi:10.1530/eje-19-0161

Willette, A. A., Bendlin, B. B., Starks, E. J., Birdsill, A. C., Johnson, S. C., Christian, B. T., Okonkwo, O. C., La Rue, A., Hermann, B. P., Koscik, R. L., Jonaitis, E. M., Sager, M. A., & Asthana, S. (2015). Association of insulin resistance with cerebral glucose uptake in late middle–aged adults at risk for alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurology, 72(9), 1013. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0613

Fan, H.-P., Zhou, Y., Zhou, Y., Jin, J., & Hu, T.-Y. (2023). Association between short-term systemic use of glucocorticoids and prognosis of cardiogenic shock: A retrospective analysis. BMC Anesthesiology, 23(1). doi:10.1186/s12871-023-02131-y

Scheen, M., Giraud, R., & Bendjelid, K. (2021). Stress hyperglycemia, cardiac glucotoxicity, and critically ill patient outcomes current clinical and pathophysiological evidence. Physiological Reports, 9(2). doi:10.14814/phy2.14713

Song, G., Liu, X., Lu, Z., Guan, J., Chen, X., Li, Y., Liu, G., Wang, G., & Ma, F. (2025). Relationship between stress hyperglycaemic ratio (SHR) and critical illness: A systematic review. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 24(1). doi:10.1186/s12933-025-02751-3

Chen, L., Deng, H., Cui, H., Fang, J., Zuo, Z., Deng, J., Li, Y., Wang, X., & Zhao, L. (2017). Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget, 9(6), 7204–7218. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23208

Fritsche, K. L. (2015). The science of fatty acids and inflammation. Advances in Nutrition, 6(3). doi:10.3945/an.114.006940

Ma, X., Nan, F., Liang, H., Shu, P., Fan, X., Song, X., Hou, Y., & Zhang, D. (2022). Excessive intake of sugar: An accomplice of inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.988481

de Punder, K., & Pruimboom, L. (2015). Stress induces endotoxemia and low-grade inflammation by increasing barrier permeability. Frontiers in Immunology, 6. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00223

Röder, P. V., Wu, B., Liu, Y., & Han, W. (2016). Pancreatic Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 48(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2016.6

Li, M., Chi, X., Wang, Y., Setrerrahmane, S., Xie, W., & Xu, H. (2022). Trends in insulin resistance: Insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 7(1). doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01073-0

Khodabandehloo, H., Gorgani-Firuzjaee, S., Panahi, G., & Meshkani, R. (2016). Molecular and cellular mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. Translational Research, 167(1), 228–256. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2015.08.011

Fernandez-Montero, A., García-Ros, D., Sánchez-Tainta, A., Rodriguez-Mourille, A., Vela, A., & Kales, S. N. (2019). Burnout syndrome and increased insulin resistance. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 61(9), 729–734. doi:10.1097/jom.0000000000001645

Beaupere, C., Liboz, A., Fève, B., Blondeau, B., & Guillemain, G. (2021). Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(2), 623. doi:10.3390/ijms22020623

Hackett, R. A., Kivimäki, M., Kumari, M., & Steptoe, A. (2016). Diurnal cortisol patterns, future diabetes, and impaired glucose metabolism in the whitehall II cohort study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 101(2), 619–625. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2853

Liyanarachchi, K., Ross, R., & Debono, M. (2017). Human studies on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 31(5), 459–473. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2017.10.011

Hinds, J. A., & Sanchez, E. R. (2022). The role of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis in test-induced anxiety: Assessments, physiological responses, and molecular details. Stresses, 2(1), 146–155. doi:10.3390/stresses2010011

Tian, Y. E., Di Biase, M. A., Mosley, P. E., Lupton, M. K., Xia, Y., Fripp, J., Breakspear, M., Cropley, V., & Zalesky, A. (2023). Evaluation of brain-body health in individuals with common neuropsychiatric disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 80(6), 567. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0791

Reilly, S., Olier, I., Planner, C., Doran, T., Reeves, D., Ashcroft, D. M., Gask, L., & Kontopantelis, E. (2015). Inequalities in physical comorbidity: A longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open, 5(12). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009010

Cyr, S., Marcil, M.-J., Houchi, C., Marin, M.-F., Rosa, C., Tardif, J.-C., Guay, S., Guertin, M.-C., Genest, C., Forest, J., Lavoie, P., Labrosse, M., Vadeboncoeur, A., Selcer, S., Ducharme, S., & Brouillette, J. (2022). Evolution of burnout and psychological distress in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A 1-year observational study. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1). doi:10.1186/s12888-022-04457-2

Sato, A., Hashimoto, T., Kimura, A., Niitsu, T., & Iyo, M. (2018). Psychological distress symptoms associated with life events in patients with bipolar disorder: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00200

Yang, J., Jia, Y., Guo, T., Zhang, S., Huang, J., Lu, H., Li, L., Xu, J., Liu, G., & Xiao, K. (2025). Comparative analysis of hpa-axis dysregulation and dynamic molecular mechanisms in acute versus chronic social defeat stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(13), 6063. doi:10.3390/ijms26136063

Valli, I., Crossley, N. A., Day, F., Stone, J., Tognin, S., Mondelli, V., Howes, O., Valmaggia, L., Pariante, C., & McGuire, P. (2016). HPA-axis function and grey matter volume reductions: Imaging the diathesis-stress model in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Translational Psychiatry, 6(5). doi:10.1038/tp.2016.68

Abe, K., Tei, S., Takahashi, H., & Fujino, J. (2022). Structural brain correlates of burnout severity in medical professionals: A voxel-based morphometric study. Neuroscience Letters, 772, 136484. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136484

White, S., Mauer, R., Lange, C., Klimecki, O., Huijbers, W., & Wirth, M. (2023). The effect of plasma cortisol on hippocampal atrophy and clinical progression in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, 15(3). doi:10.1002/dad2.12463

Tao, N., Zhang, J., Song, Z., Tang, J., & Liu, J. (2015). Relationship between job burnout and neuroendocrine indicators in soldiers in the xinjiang arid desert: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(12), 15154–15161. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121214977

Serrano, F. T., Calderón Nossa, L. T., Gualdrón Frías, C. A., Mogollón G., J. D., & Mejía, C. R. (2023). Burnout syndrome and depression in students of a colombian medical school, 2018. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría (English Ed.), 52(4), 345–351. doi:10.1016/j.rcpeng.2021.09.001

Richemond, D., Needham, M., & Jean, K. (2022). The effects of nurse burnout on patient experiences. Open Journal of Business and Management, 10(05), 2805–2828. doi:10.4236/ojbm.2022.105139

Kiratipaisarl, W., Surawattanasakul, V., & Sirikul, W. (2024). Individual and organizational interventions to reduce burnout in resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medical Education, 24(1). doi:10.1186/s12909-024-06195-3

Gómez-Polo, C., Casado, A. M., & Montero, J. (2022). Burnout syndrome in dentists: Work-related factors. Journal of Dentistry, 121, 104143. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104143

Rosales-Ricardo, Y., & Ferreira, J. P. (2022). Effects of physical exercise on burnout syndrome in university students. MEDICC Review, 24(1), 36. doi:10.37757/mr2022.v24.n1.7

Hilcove, K., Marceau, C., Thekdi, P., Larkey, L., Brewer, M. A., & Jones, K. (2020). Holistic nursing in practice: Mindfulness-based yoga as an intervention to manage stress and burnout. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 39(1), 29–42. doi:10.1177/0898010120921587

Pietrelli, A., Matković, L., Vacotto, M., Lopez-Costa, J. J., Basso, N., & Brusco, A. (2018). Aerobic exercise upregulates the BDNF-serotonin systems and improves the cognitive function in rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 155, 528–542. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2018.05.007

Taylor, H., Cavanagh, K., Field, A. P., & Strauss, C. (2022). Health care workers’ need for headspace: Findings from a multisite definitive randomized controlled trial of an unguided digital mindfulness-based self-help app to reduce healthcare worker stress. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 10(8). doi:10.2196/31744

Ameli, R., Sinaii, N., West, C. P., Luna, M. J., Panahi, S., Zoosman, M., Rusch, H. L., & Berger, A. (2020). Effect of a brief mindfulness-based program on stress in health care professionals at a US biomedical research hospital. JAMA Network Open, 3(8). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13424

Lamothe, M., Rondeau, É., Duval, M., McDuff, P., Pastore, Y. D., & Sultan, S. (2020). Changes in hair cortisol and self-reported stress measures following mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR): A proof-of-concept study in pediatric hematology-oncology professionals. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 41, 101249. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101249

Profit, J., Adair, K. C., Cui, X., Mitchell, B., Brandon, D., Tawfik, D. S., Rigdon, J., Gould, J. B., Lee, H. C., Timpson, W. L., McCaffrey, M. J., Davis, A. S., Pammi, M., Matthews, M., Stark, A. R., Papile, L.-A., Thomas, E., Cotten, M., Khan, A., & Sexton, J. B. (2021). Randomized controlled trial of the “wiser” intervention to reduce healthcare worker burnout. Journal of Perinatology, 41(9), 2225–2234. doi:10.1038/s41372-021-01100-y

Linzer, M., Poplau, S., Grossman, E., Varkey, A., Yale, S., Williams, E., Hicks, L., Brown, R. L., Wallock, J., Kohnhorst, D., & Barbouche, M. (2015). A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: Results from the healthy work place (HWP) study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(8), 1105–1111. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4

Kiser, S. B., Sterns, J. D., Lai, P. Y., Horick, N. K., & Palamara, K. (2024). Physician coaching by professionally trained peers for burnout and well-being. JAMA Network Open, 7(4). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5645

Linzer, M., Jin, J. O., Shah, P., Stillman, M., Brown, R., Poplau, S., Nankivil, N., Cappelucci, K., & Sinsky, C. A. (2022). Trends in clinician burnout with associated mitigating and aggravating factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum, 3(11). doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4163

DeChant, P. F., Acs, A., Rhee, K. B., Boulanger, T. S., Snowdon, J. L., Tutty, M. A., Sinsky, C. A., & Thomas Craig, K. J. (2019). Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: A systematic review. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 3(4), 384–408. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.07.006

Shanafelt, T. D., Hasan, O., Dyrbye, L. N., Sinsky, C., Satele, D., Sloan, J., & West, C. P. (2015). Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(12), 1600–1613. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

Salvagioni, D. A., Melanda, F. N., Mesas, A. E., González, A. D., Gabani, F. L., & Andrade, S. M. (2017). Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLOS ONE, 12(10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185781

Liyanarachchi, K., Ross, R., & Debono, M. (2017). Human studies on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 31(5), 459–473. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2017.10.011

Adam, D., Berschick, J., Schiele, J. K., Bogdanski, M., Schröter, M., Steinmetz, M., Koch, A. K., Sehouli, J., Reschke, S., Stritter, W., Kessler, C. S., & Seifert, G. (2023). Interventions to reduce stress and prevent burnout in healthcare professionals supported by digital applications: A scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1231266

Hsu, H.-C., Lee, H.-F., Hung, H.-M., Chen, Y.-L., Yen, M., Chiang, H.-Y., Chow, L.-H., Fetzer, S. J., & Mu, P.-F. (2024). Effectiveness of individual-based strategies to reduce nurse burnout: An umbrella review. Journal of Nursing Management, 2024, 1–13. doi:10.1155/2024/8544725