Comparing Minds and Machines: What We’ve Learned About Learning

Jaron Ezekiel

Illustrations by Sarah McDonald

Do you think you could tell whether you were conversing with an artificial intelligence (AI) or a human? In 1950, mathematician Alan Turing proposed the Turing Test, a hypothetical assessment of the intelligence of AI [1]. In the test, an observer reads through a conversation between an AI and another human [1]. If they cannot tell which conversant is the real person, then the AI is considered to have achieved human-like intelligence [1]. While the Turing Test remains controversial as a measure of intelligence, some find that AI can now pass what was once considered a benchmark only achievable by human intelligence [2]. But how does human-like intelligence come to be? It seems to be made possible by biological neural networks (BNNs), which are collections of interconnected neurons — the basic cell units of the brain [3]. Neurons extend throughout our entire bodies, from head to toe, comprising the complex information-processing systems collectively known as the nervous system [4]. Working together, neurons allow eyes to see, tongues to taste, and fingers to feel. Using the nervous system as a blueprint, AI designs have strived to imitate the structure of connected units through nodes, which serve as analogs to neurons [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. The story began in the 1940s, when researchers built the first mathematical model of a neuron, showing that simple units could interact to perform logical reasoning [5]. These types of AI, in which connected units process inputs to produce outputs, are called artificial neural networks (ANNs) — a term inspired by their similarities to BNNs — and are the systems that underlie leading AI models, such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Siri [3]. However, ANNs are fundamentally different from BNNs in numerous ways. ANNs are far less efficient and have distinct structures and activation mechanisms, but one of their most significant differences is how they learn new information [10, 11]. The fundamental differences in learning mechanisms between ANNs and BNNs demonstrate that ANNs function more as loose analogies than as accurate models of biological cognition.

From Neurons to Nodes: Inside Biological and Artificial Neural Networks

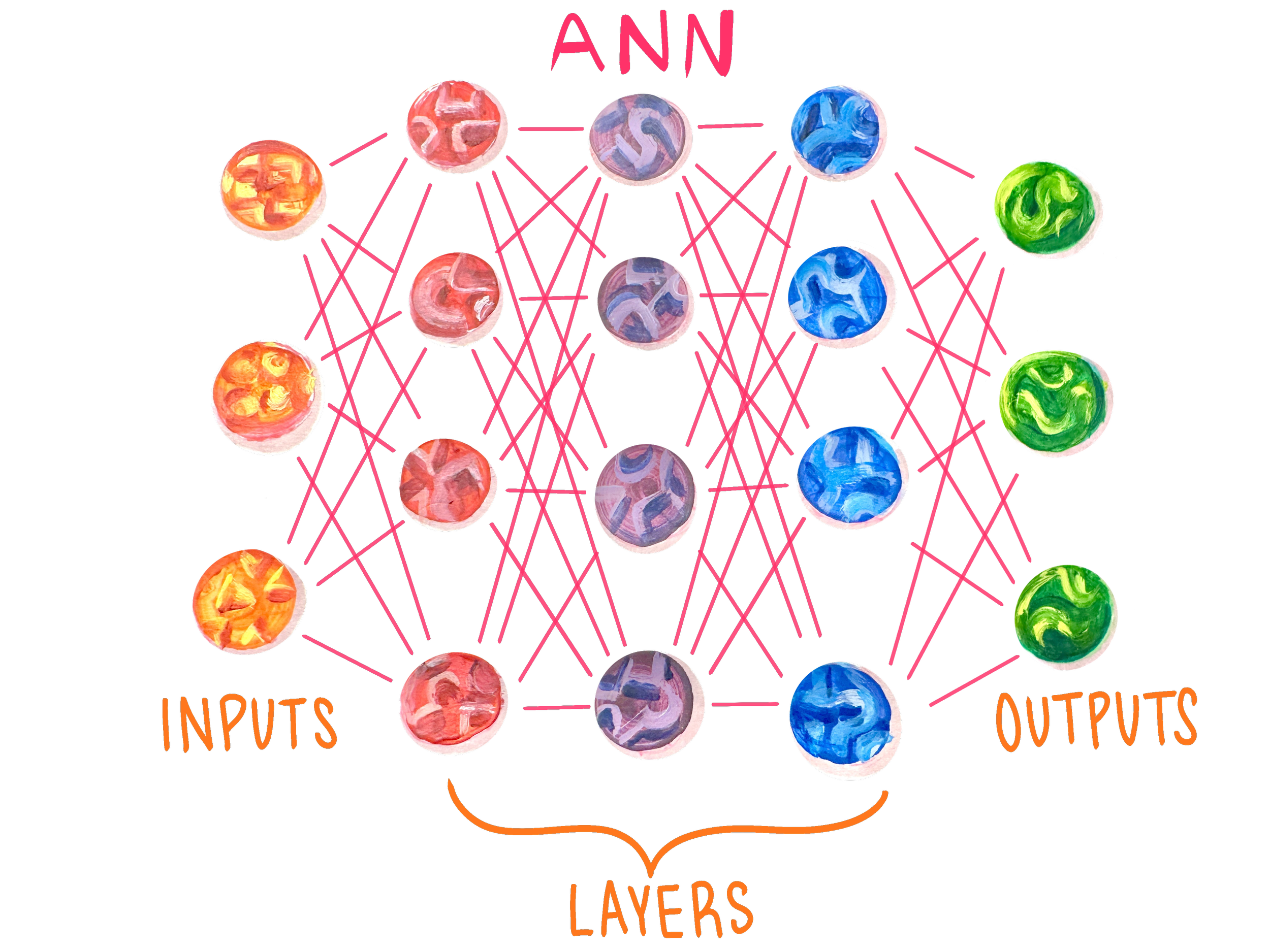

To fully understand the similarities and differences between BNNs and ANNs, we first must grasp their basic anatomy and how they function and learn. In a broad sense, both ANNs and BNNs function through a structure of interconnected units that contribute to the output produced [12]. However, upon closer examination, an overwhelming number of differences emerge [12]. While BNNs and their units are physical structures that have evolved over more than half a billion years to process and react advantageously to their environment, ANNs are virtual, human-made structures whose primary goal is not to survive, but instead to perform specific, preconfigured tasks [12, 13, 14]. BNNs are composed of up to hundreds of billions of neurons, which support information processing and are interwoven in elaborate ways that are not yet fully understood [12]. ANNs, on the other hand, are composed of layers of up to billions of virtual nodes that use mathematical functions to pass signals from layer to layer [3]. Each connection between nodes has an associated weight depending on its importance and projected influence on the output.

The number, organization, and unique connections of units in BNNs and ANNs play a large role in determining the degree of complexity to which the overall network can process and respond. [15, 16]. For example, the simplest organisms with sensory systems have neuronal counts ranging into the hundreds and are limited to basic survival instincts [17]. However, complex organisms like humans can have billions of neurons, fostering elaborate thought and learning [17]. Similarly, ANNs are limited by the number and degree of interconnectedness of their nodes [11]. For example, a simple ANN designed to recognize handwritten numbers may contain around 450 nodes, whereas a more complicated ANN, such as the one underlying ChatGPT, may contain trillions of nodes [18]. Although these individual units are meaningless devoid of the larger structure, in combination, they can produce an output that is both complex and substantive [19].

Despite the similarity in general structure between ANNs and BNNs, the actual mechanisms involved in the activation of these two networks differ significantly [3]. At the most basic level, neurons in BNNs are ‘all or nothing,’ meaning that they cannot be partially activated — they either send a signal or they do not [20]. The process of sending a signal from one neuron to the next is called neurotransmission, and a neuron will only fire when the combined incoming signals push it past its threshold potential [21]. Additionally, when a neuron fires, the signal it sends is always the same strength. [21]. On the other hand, ANNs have no equivalent to threshold potentials and do not follow an ‘all or nothing’ principle [11]. Instead, most ANNs involve every node sending a signal to all of its connected nodes, and the degree of the signal is subject to fluctuation [11]. A node's outgoing signal strength is dependent on that of the prior nodes in the network [11]. The actual calculation of how much one node affects another and the value, or signal strength, that node will pass on is highly complicated and involves complex mathematical functions [22]. The mechanism of ANNs differs significantly from the ‘all or nothing’ signaling of BNNs, and is one key difference between the two types of networks [11].

Another difference between ANNs and BNNs is unit connectivity and the structural organization of the connections [23, 24]. In BNNs, each neuron is connected to only a small fraction of the other neurons in the system [23]. In most ANNs, however, each node in a given layer is connected to every other node in the layers next to it [11]. ANN nodes are organized neatly into three layers: input, hidden, and output [24]. BNNs, specifically brains, are much more intricate and not as neatly partitioned [25]. The brain is roughly sectioned into areas of specialized function, but this specialization is flexible, and the boundaries between functional regions are fuzzy [25]. That being said, certain types of information flow in predictable neural pathways, as is the case with the sensory processing of visual and auditory stimuli [14, 26].

Tokenization, Typos, and the Capitol of France

The best way to break down the structure of an ANN is with an example. Let’s say you get curious and ask ChatGPT, ‘What’s the capitol of France?’ The first thing ChatGPT does is break down the prompt using its first layer of nodes — the input layer [27, 28, 29]. Each node of an input layer represents some detail about the input, typically text, images, or audio [30]. If the input is an image, then input nodes may represent individual pixels. Many ANNs rely on a process called tokenization to break the larger input up into smaller, more manageable data [27, 28]. In the case of written text, the input nodes are tokenized into smaller building blocks of text [27]. For example, the word ‘What’s’ is broken down — tokenized — into two tokens, ‘What’ and ‘’s’.

The main reason ANNs use tokenization is due to the sheer amount of storage required to process every version of a word as a separate unit [28]. While babies only need a couple of ounces of food to learn up to ten new words per day, training the most recent version of ChatGPT required the energy equivalent of multiple neighborhoods’ annual energy consumption [10, 31]. Thus, maximizing energy and storage efficiency through tokenization is vital to the performance of an ANN [10]. If you tell an ANN, ‘rewrite my lab report, but make it more science-y’, the network uses the pattern ‘[word]-y’ as a set of tokens meaning ‘like that word’. Hence, AI neural networks do not process ‘science-y’ as a term meaning ‘in a scientific way’ — the ANN does not have ‘science-y’ saved with its meaning. As such, tokenization can both help an ANN save energy and deal with words it has never encountered before [28]. Interestingly, children perform a process similar to tokenization when learning to speak [32]. If you have ever heard a toddler say ‘goed’ instead of ‘went,’ or ‘gooder’ instead of ‘better,’ it is because they have recognized patterns in language before they have learned the accurate vocabulary [32]. Similarly, ChatGPT will see that the word ‘capitol’ in the prompt is almost certainly a typo, and that the user probably meant ‘capital.’ By utilizing tokenization, ChatGPT can determine how to respond accurately from context clues rather than having an infinite internal dictionary.

Once the prompt has been tokenized into chunks that ChatGPT can digest, the processing moves into the second part of the network: the hidden layers [33]. Unlike the input layer, any one node in these hidden layers does not explicitly represent any decipherable information, hence the name ‘hidden’ [34]. The meaning in the hidden layers emerges from an intricate interaction of nodes that activate with varying intensities [3]. Every ANN has specific activation patterns that each correlate with a concept [35]. There is no specific node that corresponds to ‘Paris,’ but rather a certain pattern of activation [35]. It would be impossible to look at a node and understand exactly what it ‘means,’ because individual nodes do not carry specific meanings [34]. We cannot understand what a house looks like by staring at a single brick; a house looks like a house because all of its parts have been arranged together in a particular way. In the hidden layers, ChatGPT does not just look up the capital of France. Instead, it recognizes a relationship between ‘Capital of X’ and a country-city pair, and then looks for the strongest match for the country-city pair whose country is France: Paris. In doing so, its nodes activate in a seemingly patternless arrangement that collectively correlates to the concept of ‘Paris.’ You can think of the activation pattern as the pattern of ridges on a key, while the respective concept is the door that the key opens. Each ridge in the key has a different height, like the various intensities of individual nodes, but any one ridge is not enough to open the door, or even to know which door the key will open. You need to look at the pattern the ridges make, similar to how you need to look at the activation pattern of the whole ANN. Finally, once the ANN has done its ‘thinking’ in the hidden layers, the last step is to convert its findings into a digestible form for the human user, which is accomplished by the final section of nodes: the output layer [11]. The nodes of the output layer, like the input layer, have explicit meanings, typically in the form of tokens or words [36]. In this example, ChatGPT may convert all its computations into tokens and then sequentially link them together to create the final output: ‘The capital of France is Paris.’

Wiring and Firing: Learning from Our Mistakes

Let’s say you trust ChatGPT and commit to memory that Paris is the capital of France. How exactly does this process of remembering something work? What modifications occur in a BNN, such as your brain, that allow for the storage of this fact and its retrieval later on? The truth is that we just don’t know [20]. We have discovered some of the neural mechanisms involved, but how they give rise to the full process of remembering a new fact or learning a new skill remains unknown [20]. That being said, it is widely accepted that learning is made possible through neuroplasticity: the brain’s ability to create, remove, strengthen, and weaken the connections between its neurons, called synapses [37]. Neuroplasticity is achieved through a principle called Hebbian learning, summed up by the phrase, ‘cells that fire together, wire together’ [37]. Importantly, the converse is also true: cells that do not fire together do not wire together [12]. If a presynaptic neuron, the neuron sending the signal, and a postsynaptic neuron, the neuron receiving the signal, fire together repeatedly, their connection is strengthened, and the postsynaptic neuron becomes more responsive to signals from the presynaptic neuron [37]. This phenomenon is known as long-term potentiation (LTP) [38]. Long-term depression (LTD), on the other hand, is the weakening of connections between neurons when they do not fire together [39]. Some theories suggest that the Hebbian learning model — including both LTP and LTD — alone enables learning, while other theories suggest that it is the first step in a long chain of neural events [20]. Regardless, it is accepted that the strengthening and weakening of synapses is a crucial piece of the learning puzzle [40]. Another neural mechanism associated with learning is neurogenesis: the birth of new neurons [41]. Some evidence suggests that new neurons are constantly created in the adult brain, but that they die unless they are integrated into existing neural pathways [41]. Learning, especially through conscious effort, seems to be the way that these new neurons are integrated and thus rescued from death [41]. Although the exact mechanisms behind learning are debated, some aspects, such as neuroplasticity, Hebbian learning, and neurogenesis, are widely recognized as essential factors [20, 42].

A deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind learning gives us a better picture of how an organism modifies its future actions appropriately. To do this, organisms rely on feedback from chemical messengers called neuromodulators to decide whether or not to repeat an action [43]. Neuromodulators have widespread effects across large regions of the brain, impacting many neurons simultaneously [43]. As far as we can tell, the conscious experience of emotions is largely due to the release of neuromodulators within the brain [44]. Learning, in which feedback, such as emotions, informs future decisions, is called reinforcement learning [45]. When a curious toddler touches a lit stove, they will recoil in pain. Neurochemically speaking, this happens because touching a hot object sends signals from heat sensors in the toddler’s fingers to the brain that stimulate the release of chemicals that make the toddler feel pain [46]. Hebbian learning comes into play here by helping the toddler learn to associate a hot stove with pain [47]. While Hebbian learning may be responsible for the neural association between touching the stove and the pain signal, this will not actually change the toddler’s future behavior [48]. The toddler has to feel the pain to learn not to produce that behavior again [48]. In this way, Hebbian learning establishes the association, and reinforcement learning teaches the toddler that this association is bad and thus the action should not be repeated [48, 49].

Cracking the Code: How do ANNs learn?

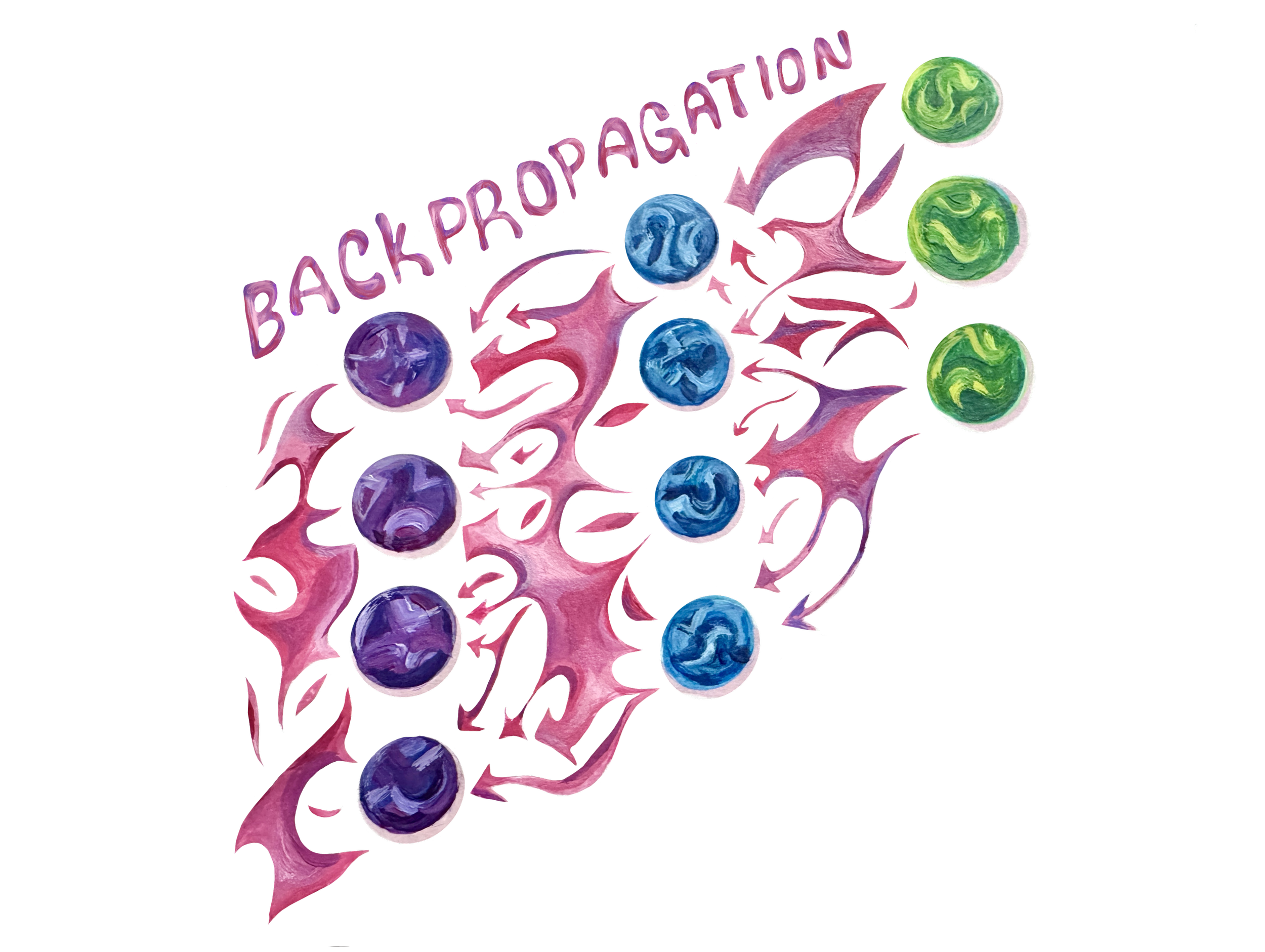

Unlike a toddler touching a hot stove, ANNs cannot feel whether their action was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ [50]. There are no chemicals that produce the feeling of being rewarded or punished in the world of computers. Instead, there are many other methods of ANN learning. The two most popular are supervised and unsupervised learning [50]. To demonstrate supervised learning, imagine ChatGPT is still in training when it’s asked, ‘What’s the capital of France?’ If it responds with ‘Paris,’ great. However, since ChatGPT is still being trained, it will likely instead come up with an incorrect answer, like ‘London,’ or perhaps just plain gibberish. The important catch with supervised learning is that the ANN is corrected by an external agent [51]. Once the correct answer is provided, the ANN can update its node weights, or the connection between nodes that depends on the importance and projected influence on the output, to be slightly more accurate next time [11, 51]. The most widespread learning mechanism in ANNs is the backpropagation algorithm, which updates connection weights after receiving feedback in order to increase response accuracy [52]. If ChatGPT responds with ‘London,’ then the backpropagation algorithm will backtrack through the network by starting with the output layer, and assessing how much each node contributed to the incorrect answer, and then adjusting their weights to minimize the future prediction of ‘London,’ while maximizing the future prediction of ‘Paris’ [52]. Interestingly, there is no known learning mechanism equivalent to backpropagation in BNNs [13]. In other words, the primary method that ANNs use to learn is absent in nature as far as we can currently tell. Instead, the major learning mechanisms employed in nature seem to be local — that is, a neuron firing will only affect the connections between that neuron and immediately subsequent neurons [53]. Unlike a toddler learning the valuable lesson of not touching a lit stove through just one experience, backpropagation must be repeated a vast number of times to reliably minimize error [8, 54].

In unsupervised learning, the ANN still produces outputs, but it is not subsequently corrected [51]. Unsupervised learning usually involves finding patterns in large amounts of data, such as classifying faces or predicting words [51]. In some ways, unsupervised learning is similar to the learning of BBNs [55]. For the most part, babies learn to recognize words, faces, sounds, and objects, often without anyone explicitly labeling them [55]. Hearing the word ‘apple’ when an apple is present may teach a baby that the sound ‘apple’ means the shiny red fruit in front of them [55]. This connection of the word ‘apple’ to the physical object, flavor, and scent is made possible by Hebbian learning [37]. However, unsupervised learning in ANNs lacks the physical nature of biological learning and is far more specialized than the learning of a toddler who must navigate the complexities of both the physical and emotional world [51]. In its initial training phase, ChatGPT was left unsupervised to predict ensuing words by identifying patterns across a vast number of books, websites, and articles, ultimately processing hundreds of billions of tokens over the span of several months [29].

When ANNs Upgrade: Borrowing Tricks from Real Brains

Certain features of BNNs, such as their impressive adaptability and efficiency, make them a useful model for the future growth and development of many kinds of ANNs [19]. Recent advancements have further bridged the gap between ANNs and BNNs. For example, one biological factor that differentiates the two is that during development, there is a genetic constraint; the genome — an organism’s complete genetic material — is nowhere near complex enough to encompass all the intricacies of the brain, so this information must somehow be condensed [23, 56]. To mirror this biological constraint in their ANN, researchers introduced ‘innate,’ pre-trained wiring to their ANN, and this ANN performed exceptionally well, even before the regular training phase [23]. Like a giraffe being able to walk almost immediately after being born, this ANN seemingly came into the world with predisposed capacities, namely to classify images and recognize patterns in general [23].

Other ANN models have bridged the gap to BNNs using different methods. Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), an exciting branch of ANNs, have risen in popularity because of their biological plausibility: they mirror neural signaling much more closely than other ANNs, and they rarely use backpropagation [57, 6]. SNNs are also more energetically efficient than other ANNs, further minimizing the energy disparity between ANNs and BNNs [6, 58]. Other models have been able to approximate backpropagation-like learning solely with Hebbian learning mechanisms [9]. Using local weight adjustments, one ANN model was able to learn solely via Hebbian learning in a manner very similar to using backpropagation [9]. Liquid Neural Networks, another branch of ANNs, can constantly reconfigure themselves by changing the mathematical equations behind their weights, somewhat resembling the adaptive nature of BNNs [59]. Regardless, ANN learning has a long way to go before it can accurately mirror the energy consumption, mechanisms, and adaptability of BNN learning [60, 61].

What We Teach Machines, and What Machines Teach Us

Insights into how brains work have been instrumental in developing more accurate and efficient ANNs [62]. But what about the reverse: what can ANNs teach us about the human mind? For one, contemporary ANN models demonstrate that information can be stored and retrieved in the organization of connected units [19]. They support the idea that knowing a concept does not mean having a neuron in your brain that explicitly codes for that concept, but rather an activation pattern of interconnected neurons that collectively represent the concept [35]. By highlighting this parallel, the development of ANNs has given us valuable insight into biological pattern recognition as well as language processing. Although it may seem intuitive to us today, the notion that organisms process information with many individual units working together was not a mainstream viewpoint until the first AI system was proposed in the 1940s [63]. That being said, AI is still in its infancy compared to its biological counterparts. While BNN learning involves neuroplasticity, Hebbian mechanisms, and emotional feedback, ANNs learn mathematically, primarily through backpropagation — a process biology has never been known to use [12, 13, 14]. The differences between the two kinds of networks are striking, and they demonstrate that, no matter how human an ANN may seem in conversation or how well it appears to pass the Turing Test, many argue its learning and functioning remain fundamentally unlike those of our brains [12].

References

Mitchell, M. (2024). The Turing Test and our shifting conceptions of intelligence. Science, 385(6710). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adq9356

Jones, C. R., & Bergen, B. K. (2025). Large Language Models Pass the Turing Test. ArXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2503.23674

Han, S.-H., Kim, K. W., Kim, S., & Youn, Y. C. (2018). Artificial Neural Network: Understanding the Basic Concepts without Mathematics. Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders, 17(3), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.12779/dnd.2018.17.3.83

Murtazina, A., & Adameyko, I. (2023). The peripheral nervous system. Development, 150(9). https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.201164

He, J., Yang, H., He, L., & Zhao, L. (2021). Neural networks based on vectorized neurons. Neurocomputing, 465, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2021.09.006

Yamazaki, K., Vo-Ho, V.-K., Bulsara, D., & Le, N. (2022). Spiking Neural Networks and Their Applications: A Review. Brain Sciences, 12(7), 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12070863

Kell, A. J. E., Yamins, D. L. K., Shook, E. N., Norman-Haignere, S. V., & McDermott, J. H. (2018). A Task-Optimized Neural Network Replicates Human Auditory Behavior, Predicts Brain Responses, and Reveals a Cortical Processing Hierarchy. Neuron, 98(3), 630-644.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.044

Zador, A. M. (2019). A critique of pure learning and what artificial neural networks can learn from animal brains. Nature Communications, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11786-6

Whittington, J. C. R., & Bogacz, R. (2017). An Approximation of the Error Backpropagation Algorithm in a Predictive Coding Network with Local Hebbian Synaptic Plasticity. Neural Computation, 29(5), 1229–1262. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco_a_00949

Jiang, P., Sonne, C., Li, W., You, F., & You, S. (2024). Preventing the Immense Increase in the Life-Cycle Energy and Carbon Footprints of LLM-Powered Intelligent Chatbots. Engineering, 40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2024.04.002

Zhang, Z. (2016). A gentle introduction to artificial neural networks. Annals of Translational Medicine, 4(19), 370–370. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2016.06.20

Schmidgall, S., Ziaei, R., Achterberg, J., Kirsch, L., Hajiseyedrazi, S. P., & Eshraghian, J. (2024). Brain-inspired learning in artificial neural networks: A review. APL Machine Learning, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0186054

Lillicrap, T. P., Santoro, A., Marris, L., Akerman, C. J., & Hinton, G. (2020). Backpropagation and the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 21(6), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-020-0277-3

Pham, T. Q., Matsui, T., & Chikazoe, J. (2023). Evaluation of the Hierarchical Correspondence between the Human Brain and Artificial Neural Networks: A Review. Biology, 12(10), 1330–1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12101330

Bertolero, M. A., Yeo, B. T. T., Bassett, D. S., & D’Esposito, M. (2018). A mechanistic model of connector hubs, modularity and cognition. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(10), 765–777. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0420-6

Raghu, M., Poole, B., Kleinberg, J., Ganguli, S., & Sohl-Dickstein, J. (2016). On the Expressive Power of Deep Neural Networks. ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1606.05336

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2017). Numbers of neurons as biological correlates of cognitive capability. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 16, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.02.004

Cherny, S. N., & Gibadullin, R. F. (2022). The Recognition of Handwritten Digits Using Neural Network Technology. 2022 International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing (ICIEAM). https://doi.org/10.1109/icieam54945.2022.9787104

Jeon, I., & Kim, T.-G. (2023). Distinctive properties of biological neural networks and recent advances in bottom-up approaches toward a better biologically plausible neural network. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2023.1092185

Langille, J. J., & Brown, R. E. (2018). The Synaptic Theory of Memory: A Historical Survey and Reconciliation of Recent Opposition. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2018.00052

Kavalali, E. T. (2017). Spontaneous neurotransmission: A form of neural communication comes of age. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 96(3), 331–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24207

Zhang, Q., Shuai, B., & Lü, M. (2022). A novel method to identify influential nodes in complex networks based on gravity centrality. Information Sciences, 618, 98–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2022.10.070

Shuvaev, S., Lachi, D., Koulakov, A., & Zador, A. (2024). Encoding innate ability through a genomic bottleneck. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(38). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2409160121

Zivich, P. N., & Naimi, A. I. (2024). A primer on neural networks. American Journal of Epidemiology, 194(6), 1473–1475. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwae380

Fan, Y., Wang, R., Yi, C., Zhou, L., & Wu, Y. (2023). Hierarchical overlapping modular structure in the human cerebral cortex improves individual identification. IScience, 26(5), 106575–106575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106575

Horikawa, T., & Kamitani, Y. (2017). Generic decoding of seen and imagined objects using hierarchical visual features. Nature Communications, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15037

Rajaraman, N., Jiao, J., & Ramchandran, K. (2024). Toward a Theory of Tokenization in LLMs. ArXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2404.08335

Kaplan, G., Oren, M., Reif, Y., & Schwartz, R. (2024). From Tokens to Words: On the Inner Lexicon of LLMs. ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2410.05864

Koubâa, A., Boulila, W., Ghouti, L., Alzahem, A., & Latif, S. (2023). Exploring ChatGPT Capabilities and Limitations: A Survey. IEEE Access, 11. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2023.3326474

Kong, Q., Cao, Y., Iqbal, T., Wang, Y., Wang, W., & Plumbley, M. D. (2020). PANNs: Large-Scale Pretrained Audio Neural Networks for Audio Pattern Recognition. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 28, 2880–2894. https://doi.org/10.1109/taslp.2020.3030497

DiMaggio, D. M., Cox, A., & Porto, A. F. (2017). Updates in Infant Nutrition. Pediatrics in Review, 38(10), 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2016-0239

Capone Singleton, N., & Saks, J. (2023). Object Shape and Depth of Word Representations in Preschoolers. Journal of Child Language, 51(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000922000630

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention Is All You Need. ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762

Xu, X., Huang, S.-L., Zheng, L., & Wornell, G. W. (2022). An Information Theoretic Interpretation to Deep Neural Networks. Entropy, 24(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24010135

Xiao, P., Toivonen, H., Gross, O., Cardoso, A., Correia, J., Machado, P., Martins, P., Oliveira, H. G., Sharma, R., Pinto, A. M., Díaz, A., Francisco, V., Gervás, P., Hervás, R., León, C., Forth, J., Purver, M., Wiggins, G. A., Miljković, D., & Podpečan, V. (2020). Conceptual Representations for Computational Concept Creation. ACM Computing Surveys, 52(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3186729

Chen, P. H., Si, S., Li, Y., Chelba, C., & Hsieh, C. (2018). GroupReduce: Block-Wise Low-Rank Approximation for Neural Language Model Shrinking. ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1806.06950

Sumner, R. L., Spriggs, M. J., Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., & Kirk, I. J. (2020). The role of Hebbian learning in human perception: a methodological and theoretical review of the human Visual Long-Term Potentiation paradigm. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 115, 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.013

He, K., Huertas, M., Hong, Su Z., Tie, X., Hell, Johannes W., Shouval, H., & Kirkwood, A. (2015). Distinct Eligibility Traces for LTP and LTD in Cortical Synapses. Neuron, 88(3), 528–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.037

Fox, K., & Stryker, M. (2017). Integrating Hebbian and homeostatic plasticity: introduction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1715), 20160413. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0413

Kelvington, B. A., Nickl-Jockschat, T., & Abel, T. (2022). Neurobiological insights into twice-exceptionality: Circuits, cells, and molecules. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 195(107684), 107684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2022.107684

Song, J., Olsen, R. H. J., Sun, J., Ming, G., & Song, H. (2016). Neuronal Circuitry Mechanisms Regulating Adult Mammalian Neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 8(8), a018937. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a018937

Kempermann, G. (2022). What Is Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Good for? Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.852680

Bazzari, A. H., & Parri, H. R. (2019). Neuromodulators and Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in Learning and Memory: A Steered-Glutamatergic Perspective. Brain Sciences, 9(11), 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9110300

Pereira, A., & Wang, F. (2016). Neuromodulation, Emotional Feelings and Affective Disorders. Mens Sana Monographs, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.154533

Recht, B. (2018). A Tour of Reinforcement Learning: The View from Continuous Control. Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-control-053018-023825

Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A., Verri, W. A., & Chiu, I. M. (2017). Nociceptor Sensory Neuron–Immune Interactions in Pain and Inflammation. Trends in Immunology, 38(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2016.10.001

Fuchsberger, T., Stockwell, I., Woods, M., Brzosko, Z., Greger, I. H., & Paulsen, O. (2025). Dopamine increases protein synthesis in hippocampal neurons enabling dopamine-dependent LTP. ELife, 13. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.100822.2

Frémaux, N., & Gerstner, W. (2016). Neuromodulated Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity, and Theory of Three-Factor Learning Rules. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2015.00085

Brzosko, Z., Zannone, S., Schultz, W., Clopath, C., & Paulsen, O. (2017). Sequential neuromodulation of Hebbian plasticity offers mechanism for effective reward-based navigation. ELife, 6. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.27756

Alzubaidi, L., Zhang, J., Humaidi, A. J., Al-Dujaili, A., Duan, Y., Al-Shamma, O., Santamaría, J., Fadhel, M. A., Al-Amidie, M., & Farhan, L. (2021). Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. Journal of Big Data, 8(1), 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00444-8

Sarker, I. H. (2021). Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Computer Science, 2(3), 1–21. Springer. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42979-021-00592-x

Li, M. (2024). Comprehensive Review of Backpropagation Neural Networks. Academic Journal of Science and Technology, 9(1), 150–154. https://doi.org/10.54097/51y16r47

Speranza, L., di Porzio, U., Viggiano, D., de Donato, A., & Volpicelli, F. (2021). Dopamine: The Neuromodulator of Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity, Reward and Movement Control. Cells, 10(4), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040735

Fan, Q., Wu, W., & Zurada, J. M. (2016). Convergence of batch gradient learning with smoothing regularization and adaptive momentum for neural networks. SpringerPlus, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-1931-0

Twomey, K. E., & Westermann, G. (2017). Learned Labels Shape Pre-speech Infants’ Object Representations. Infancy, 23(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12201

Goldman, A. D., & Landweber, L. F. (2016). What Is a Genome? PLOS Genetics, 12(7), e1006181. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006181

Zeng, Y., Zhao, D., Zhao, F., Shen, G., Dong, Y., Lu, E., Zhang, Q., Sun, Y., Liang, Q., Zhao, Y., Zhao, Z., Fang, H., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Liu, X., Du, C., Kong, Q., Ruan, Z., & Bi, W. (2023). BrainCog: A spiking neural network based, brain-inspired cognitive intelligence engine for brain-inspired AI and brain simulation. Patterns, 4(8), 100789–100789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2023.100789

Dutta, S., Kumar, V., Shukla, A., Mohapatra, N. R., & Ganguly, U. (2017). Leaky Integrate and Fire Neuron by Charge-Discharge Dynamics in Floating-Body MOSFET. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07418-y

Hasani, R., Lechner, M., Amini, A., Rus, D., & Radu Grosu. (2020). Liquid Time-constant Networks. ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2006.04439

Maass, W. (2023). How can neuromorphic hardware attain brain-like functional capabilities? National Science Review, 11(5). https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwad301

Ostrau, C., Klarhorst, C., Thies, M., & Rückert, U. (2022). Benchmarking Neuromorphic Hardware and Its Energy Expenditure. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.873935

Abiodun, O. I., Jantan, A., Omolara, A. E., Dada, K. V., Mohamed, N. A., & Arshad, H. (2018). State-of-the-art in artificial neural network applications: A survey. Heliyon, 4(11), e00938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00938

Doroudi, S. (2022). The intertwined histories of artificial intelligence and education. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 33, 885–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-022-00313-2