PANDAS: A Not so Fluffy Disorder

Cailey Metter

Illustrations by Leo Malkhe

June B. Kelly is six years old. Like many children her age, she enjoys playing pretend, reading fanciful stories, and performing magic tricks for her friends and family. June’s life has changed after contracting strep throat multiple times. Following her illnesses, June’s mother noticed some concerning changes in her child. June became preoccupied with germs and contamination, causing her extreme stress. She began washing her hands excessively throughout the day, to the point of developing painful cuts and abrasions on her skin. June developed other unusual habits, such as tapping objects three times before picking them up, only eating food she knew for certain was not contaminated by germs, and flinching with uncontrollable movements. Her mother was dumbfounded, unable to think of a reason for June’s new behaviours. One day, June came home in tears after a classmate touched her sandwich during lunch. Despite her mother’s attempts to comfort her, June was inconsolable. She called June’s pediatrician to find out what was behind June’s new behaviors, and following a visit to a psychiatrist, June was diagnosed with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). June’s mother was shocked to discover that PANDAS is a rare case where a common strep infection can have long-lasting effects on the brain. June’s strep infections, like all strep infections, were caused by the Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria, which spreads through coughing or skin contact [1]. Antibiotics, such as amoxicillin or penicillin, are commonly used to treat strep infections [2]. However, in rare cases, even after antibiotic treatment, strep bacteria can leave behind physical and psychological damage that may persist throughout a child’s life [2, 3, 4]. Though June is fictional, her case is based on the true stories of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) and their known symptoms.

The Un-Bear-able Consequences of a Strep Infection

After June’s most recent strep infection, she began to experience symptoms comparable to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a psychological condition characterized by obsessions and compulsions [5]. Obsessions are recurring, unwanted thoughts or urges that can cause intense distress to the individual experiencing them [5]. Common obsessions include a preoccupation with germs, organization, or thoughts of harm [5]. Compulsions are ritualistic, repetitive behaviors performed in response to the anxiety caused by an obsession [5, 6]. Compulsions can include excessive cleaning, repetitively checking or touching a surface, or fixating on the exact arrangement of objects [5, 6]. A person must have obsessive thoughts, compulsive behaviors, or both to be diagnosed with OCD [5, 7]. June personally experiences germ-related obsessions and compulsions. Her hand-washing compulsion is an attempt to soothe her contamination obsession. Additionally, she experiences uncontrollable facial and arm movements, which are comparable to tics. Tics are quick, uncontrollable movements or sounds that manifest from physical urges, while compulsions stem from a desire to soothe mental distress [8, 9, 10]. She is one of the rare cases in which a strep infection has led to a child developing tics as well as OCD symptoms [11]. June’s symptoms are distinct from OCD because they were brought on suddenly following her strep infections [12].

After June’s psychiatrist diagnosed her with PANDAS, June’s mother spent hours researching her daughter’s condition. PANDAS describes the onset or worsening of OCD-like symptoms and/or tic-related disorder symptoms in a prepubescent child following a strep infection [12]. Receiving a PANDAS diagnosis also typically requires the presence of another neurological symptom, such as excessive physical movement, impulsivity, restrictive eating, separation anxiety, or a deterioration in handwriting, which are not necessarily symptoms of OCD [11, 12, 13]. Contracting strep multiple times increases the risk of a child developing PANDAS [14]. The physiological mechanism underlying PANDAS is still uncertain, and its symptoms overlap extensively with other neuropsychiatric disorders [15]. As a result, PANDAS remains a heavily disputed diagnosis and is an exclusionary diagnosis, meaning it is only diagnosed when no other diagnosis matches the symptoms [15, 16, 17].

Bamboo-zled: Strep Playing Tricks on the Immune System

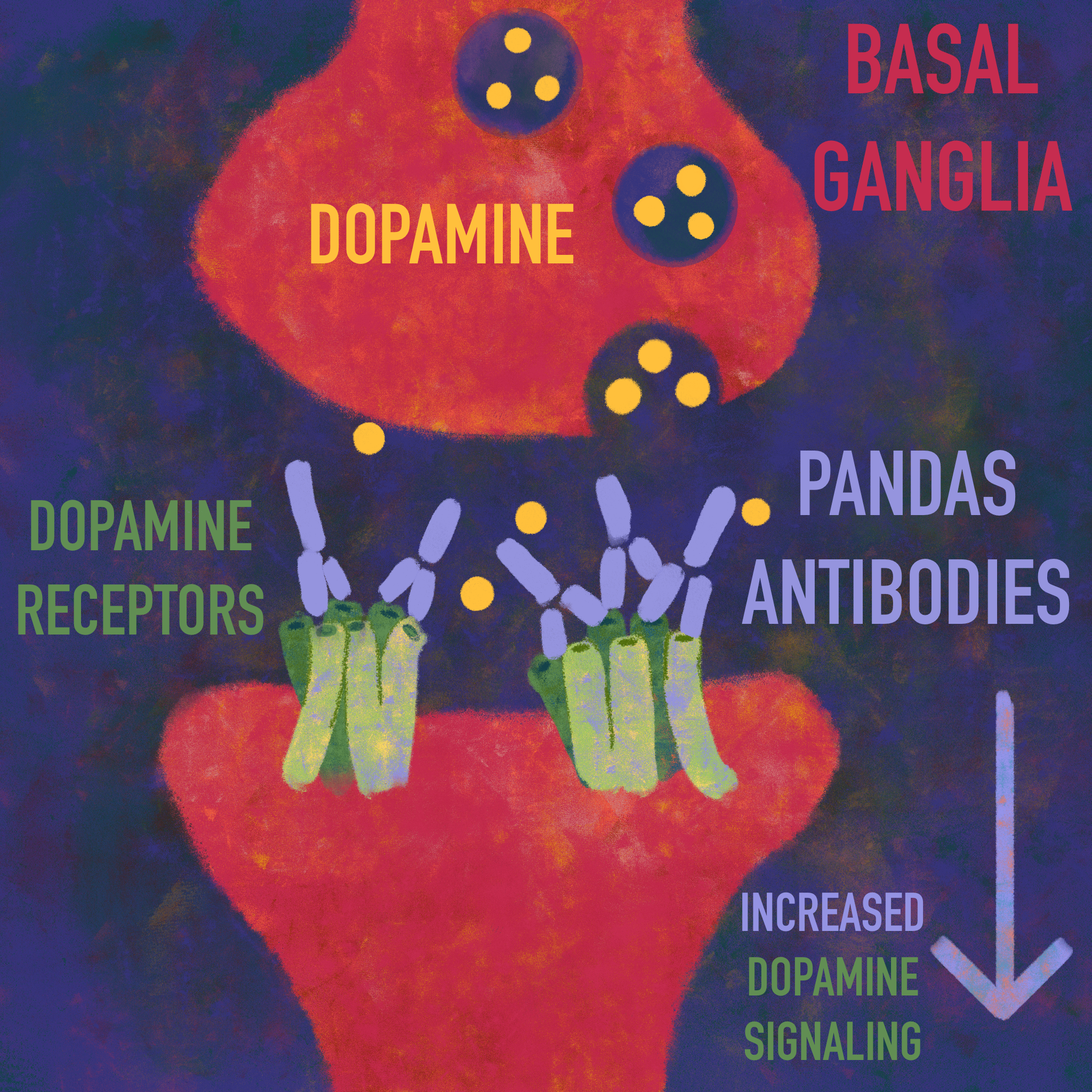

The leading explanation for the symptoms observed in PANDAS is molecular mimicry [18]. Molecular mimicry is when proteins from foreign bodies, such as bacteria and viruses, resemble proteins already present in the human body [19, 20, 21]. As a result, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own proteins, a phenomenon called cross-reactivity [18]. When infected by strep bacteria, a healthy immune system releases proteins called antibodies, which work to eliminate foreign pathogens [22]. In the case of PANDAS, these antibodies also cross-react with proteins in the brain that share structural similarities with the proteins on strep bacteria [23, 24]. The immune system also releases small proteins called cytokines that respond to infection by regulating inflammation, the process by which the body eliminates foreign substances, like strep bacteria [16, 25]. There is an overabundance of these cytokines, leading to more severe inflammation in the brain than is typical, which has the potential to damage healthy tissues [16, 25, 26]. Normally, a tightly regulated border of cells called the blood-brain barrier (BBB) controls which substances from the blood are allowed to enter the brain, and in this case, shields the brain from antibodies [22, 27]. In PANDAS, it is proposed that the inflammation triggers the release of a specific cytokine called IL-17, which disrupts proteins that seal the BBB [28, 29]. The damage caused by the IL-17 cytokines renders the BBB more permeable, allowing immune cells to pass through the BBB and cross-react with a part of the brain called the basal ganglia [15, 16]. The basal ganglia are a collection of brain structures associated with emotional processing and movement [24, 30]. Proteins in strep bacteria have structural similarities to a type of protein in the basal ganglia called dopamine receptors [23, 31, 32]. When strep bacteria enter the body, antibodies cross-react with dopamine receptors in the basal ganglia [11, 33]. Dopamine is a chemical in the brain that regulates motor control, motivation, and emotion [34, 35, 36]. In the proposed molecular mimicry mechanism, it is thought that antibodies bind to dopamine receptors in the basal ganglia, leading to increased dopamine signaling [37]. Increased dopamine signaling may lead to symptoms associated with PANDAS, such as tics and emotional dysregulation [33]. While there are excellent theories on the true mechanism of PANDAS, more research is needed to know for sure which explanation is accurate [33].

Treating PANDAS: It’s Not So Black and White

Little June may not be able to say for certain whether her OCD and tic-like symptoms are a direct result of her multiple strep infections, but either way, there are options to help relieve her symptoms. When June initially developed strep, she was treated using antibiotics [38, 39]. Another round of antibiotics successfully addressed all of June’s PANDAS symptoms for some time, and her mother was overjoyed to see her daughter feel somewhat better. Antibiotics have the potential to reduce PANDAS symptoms to a manageable level or even eliminate them [13, 40]. Unfortunately, the long-term use of antibiotics has several negative consequences, such as bacteria growing resistant to the medication, thereby causing the antibiotic treatment to lose efficacy [40, 41, 42]. June’s mother needed to find a different treatment for her daughter. One alternative is intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), where blood is infused with thousands of healthy donor antibodies, reducing inflammation and increasing immunity to illness [43, 44]. IVIG appears to have the strongest long-term success in treating PANDAS symptoms, despite its invasive nature [45, 46]. Though the long-term results of IVIG can be unreliable, as PANDAS symptoms tend to wax and wane over time [46]. IVIG has been shown to reduce the symptoms of children with PANDAS drastically, but June’s mother was hesitant to put her daughter through IVIG treatment as it is underresearched [47]. Distressed, June’s mother turned to exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy to help her child find peace again.

For many people with PANDAS, behavioral therapy helps to alleviate symptoms [13]. ERP is a common treatment for the OCD-like symptoms associated with PANDAS [13]. In ERP, individuals are placed in situations that trigger their compulsions and asked to resist engaging in their desired action [13, 48]. For example, an individual with a contamination obsession may be instructed to touch something they perceive as ‘dirty’ and not wash their hands immediately afterward [49]. Many people are reluctant to engage in ERP since it deliberately places them in stressful situations, and the individual’s reluctance usually depends on the severity of their OCD [13]. June did her best to follow her ERP therapist's instructions, but when she was asked to touch a garbage can and not wash her hands afterwards, she was too terrified to complete the task. June was making little progress in ERP therapy, and she begged her mother to find another course of treatment. For individuals with PANDAS who develop tic-related symptoms, a common behavioral treatment is habit reversal training, where doctors encourage individuals to identify when a tic is about to occur and then engage in a voluntary action to suppress it [13, 50]. There are many ways to treat the symptoms of PANDAS individually, and the correct course of treatment depends on symptom severity and one’s individual needs [13]. Though ERP is effective for many individuals with PANDAS, the discomfort of being placed in stressful situations regularly ultimately proved too much for June, and she was not able to complete ERP treatment. June’s mother would have to find another course of treatment for her daughter.

Having exhausted clinical treatment options, which were either ineffective or made June too distressed to continue, June’s mother decided to have her try a different approach involving herbs and vitamins. Approximately 40% of individuals with OCD end up dissatisfied with outcomes using traditional medicine, and so they may turn to herbal medicine or vitamin supplements as a result [51]. Although more research is needed on these alternative forms of medicine, individuals seek out herbal treatments due to their less severe side effects [52, 53]. For example, some tic-disorder pharmaceuticals have negative side effects such as weakness, stomach problems, and cognitive issues, depending on the prescribed medication [54, 55]. Many people do not see a benefit from using pharmaceuticals to treat their OCD [56]. Antidepressants that are used to treat OCD can have negative side effects such as anxiety, aggression, low blood sodium levels, and restlessness [13, 56]. There is some evidence to indicate that herbal medicine and vitamin supplements may effectively relieve symptoms for people with PANDAS [57]. For instance, individuals with severe PANDAS-related symptoms tend to have lower levels of vitamin D, which is important to the functioning of the immune system and metabolic pathways [57, 58, 59]. Increasing a child’s intake of vitamin D through increased sun exposure, certain foods, or supplements may decrease the severity of neuropsychiatric PANDAS symptoms [57, 60]. People with OCD may also have lower levels of vitamin B12, which helps the nervous system function properly, plays a part in metabolism, and creates red blood cells and DNA [58, 59, 61]. Due to vitamin B12’s many roles, especially its function in the nervous system, increased vitamin B12 intake could improve symptoms of OCD when used with some other form of treatment, such as an antidepressant [59, 61, 62]. Once June’s mother thoroughly researched the potential role of vitamins in OCD and PANDAS, she made sure her daughter got enough sunlight and had a healthy breakfast each day consisting of meat, eggs, and a supplement of cod liver oil to increase her daughter’s intake of vitamin D and vitamin B12 [63, 64].

Through further research, June’s mother found another alternative to pharmaceuticals for the treatment of June’s OCD-like symptoms: saffron [65, 66]. Saffron is a spice used in herbal medicine, and it can function similarly to pharmaceutical treatments for OCD [65, 67]. There are also potential herbal treatments for tic-related disorders [68]. One promising candidate is 5-Ling Granule, a patented herbal medicine with fewer side effects than traditional psychiatric medications [68]. 5-Ling Granule is essentially an herbal cocktail made from 11 different herbs commonly used in Chinese medicine [68]. The herbs in the medicine can subdue emotional hyperactivity, have sedative qualities for excessive movement, and help to combat insomnia, among other functions [68]. Other traditional Chinese medicines have also been used to treat tic-related disorders, including Bai Shao — white peony root — and Fu Ling — a medicinal fungus [53, 69, 70]. Using herbs to try to decrease PANDAS symptoms could be a valid option for parents concerned about the side effects of pharmaceuticals for their children [52].

Coming Out of Hibernation: Future Directions for the PANDAS Disorder

Following a combination of pharmaceutical and herbal treatments, June saw a reduction in her PANDAS symptoms. June was now finally able to play tag at recess with her best friends without obsessing over the thought of being contaminated by germs. PANDAS remains an unexplored disorder that affects the availability of long-term treatment options [46, 71]. Due to the lack of research around the disorder, many people affected by PANDAS have grown frustrated [46]. Some have created support groups for people with PANDAS and their loved ones, including the PANDAS Network in the United States and Canada and the PANDASHELP organization [46]. June may now have decreased PANDAS symptoms, but she still has a disorder that she must endure throughout her life. Although June experienced a decrease in her symptoms, the same can not be said for all children with the PANDAS disorder. With time, PANDAS symptoms can increase in severity and may be related to increases in suicidal ideation, but further research and more treatment options could lead to better outcomes for individuals with PANDAS [72]. Although PANDAS is currently understudied, the future may be a beacon of hope for June and others like her if time and materials are devoted to studying PANDAS.

References

Brouwer, S., Rivera-Hernandez, T., Curren, B. F., Harbison-Price, N., De Oliveira, D. M. P., Jespersen, M. G., Davies, M. R., & Walker, M. J. (2023). Pathogenesis, epidemiology and control of group a streptococcus infection. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 21(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00865-7

Biała, M., Babicki, M., Malchrzak, W., Janiak, S., Gajowiak, D., Żak, A., Kłoda, K., Gibas, P., Ledwoch, J., Myśliwiec, A., Kopyt, D., Węgrzyn, A., Knysz, B., & Leśnik, P. (2024). Frequency of Group A streptococcus infection and analysis of antibiotic use in patients with pharyngitis—a retrospective, Multicenter Study. Pathogens, 13(10), 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13100846

Grandinetti, R., Mussi, N., Pilloni, S., Ramundo, G., Miniaci, A., Turco, E., Piccolo, B., Capra, M. E., Forestiero, R., Laudisio, S., Boscarino, G., Pedretti, L., Menoni, M., Pellino, G., Tagliani, S., Bergomi, A., Antodaro, F., Cantù, M. C., Bersini, M. T., . . . Esposito, S. (2024). Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infections: a delphi study and consensus document about definition, diagnostic criteria, treatment and follow-up. Frontiers in Immunology, 15, 1420663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1420663

Prato, A., Gulisano, M., Scerbo, M., Barone, R., Vicario, C. M., & Rizzo, R. (2021). Diagnostic Approach to Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS): A Narrative Review of literature data. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 746639. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.746639

Jalal, B., Chamberlain, S. R., & Sahakian, B. J. (2023). Obsessive‐compulsive disorder: Etiology, neuropathology, and cognitive dysfunction. Brain and Behavior, 13(6), e3000. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.3000

Moreno-Amador, B., Piqueras, J. A., Rodríguez-Jiménez, T., Martínez-González, A. E., & Cervin, M. (2023). Measuring symptoms of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders using a single dimensional self-report scale. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 958015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.958015

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

Billnitzer, A., & Jankovic, J. (2020). Current Management of Tics and Tourette Syndrome: Behavioral, Pharmacologic, and Surgical Treatments. Neurotherapeutics, 17(4), 1681–1693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-020-00914-6

Katz, T. C., Khan, T. R., Chaponis, O., & Tomczak, K. K. (2024). Repetitive but not interchangeable. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 48(1), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2024.09.002

Mittal, S. O. (2020). Tics and Tourette’s syndrome. Drugs in Context, 9, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.2019-12-2

La Bella, S., Scorrano, G., Rinaldi, M., Di Ludovico, A., Mainieri, F., Attanasi, M., Spalice, A., Chiarelli, F., & Breda, L. (2023). Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS): Myth or Reality? The State of the Art on a Controversial Disease. Microorganisms, 11(10), 2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11102549

Grandinetti, R., Mussi, N., Pilloni, S., Ramundo, G., Miniaci, A., Turco, E., Piccolo, B., Capra, M. E., Forestiero, R., Laudisio, S., Boscarino, G., Pedretti, L., Menoni, M., Pellino, G., Tagliani, S., Bergomi, A., Antodaro, F., Cantù, M. C., Bersini, M. T., . . . Esposito, S. (2024). Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infections: a delphi study and consensus document about definition, diagnostic criteria, treatment and follow-up. Frontiers in Immunology, 15, 1420663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1420663

Thienemann, M., Murphy, T., Leckman, J., Shaw, R., Williams, K., Kapphahn, C., Frankovich, J., Geller, D., Bernstein, G., Chang, K., Elia, J., & Swedo, S. (2017). Clinical Management of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Part I—Psychiatric and Behavioral interventions. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 27(7), 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2016.0145

Orlovska, S., Vestergaard, C. H., Bech, B. H., Nordentoft, M., Vestergaard, M., & Benros, M. E. (2017). Association of Streptococcal Throat Infection With Mental Disorders.JAMAPsychiatry,74(7),740–746. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0995

Leonardi, L., Perna, C., Bernabei, I., Fiore, M., Ma, M., Frankovich, J., Tarani, L., & Spalice, A. (2024). Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) and Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS): Immunological Features Underpinning Controversial Entities. Children, 11(9), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091043

Foiadelli, T., Loddo, N., Sacchi, L., Santi, V., D’Imporzano, G., Spreafico, E., Orsini, A., Ferretti, A., De Amici, M., Testa, G., Marseglia, G. L., & Savasta, S. (2024). IL-17 in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of pediatric patients with acute neuropsychiatric disorders: Implications for PANDAS and PANS. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 54, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2024.11.004

Frånlund, K., & Talani, C. (2023). PANDAS – a rare but severe disorder associated with streptococcal infections; Awareness is needed. Acta Oto-Laryngologica Case Reports, 8(1), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/23772484.2023.2231146

Hutanu, A., Reddy, L. N., Mathew, J., Avanthika, C., Jhaveri, S., & Tummala, N. (2022). Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with Group A streptococci: etiopathology and diagnostic challenges. Cureus, 14(8), e27729. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27729

Cunningham, M. W. (2019). Molecular Mimicry, Autoimmunity, and Infection: The Cross-Reactive Antigens of Group A Streptococci and their Sequelae. Microbiology Spectrum, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.gpp3-0045-2018

Gagliano, A., Carta, A., Tanca, M. G., & Sotgiu, S. (2023). Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Current Perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Volume 19, 1221–1250. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s362202

Thaper, D., & Prabha, V. (2018). Molecular mimicry: An explanation for autoimmune diseases and infertility. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 88(2), e12697. https://doi.org/10.1111/sji.12697

Tien, J., Leonoudakis, D., Petrova, R., Trinh, V., Taura, T., Sengupta, D., Jo, L., Sho, A., Yun, Y., Doan, E., Jamin, A., Hallak, H., Wilson, D. S., & Stratton, J. R. (2023). Modifying antibody-FcRn interactions to increase the transport of antibodies through the blood-brain barrier. mAbs, 15(1), 2229098. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2023.2229098

Frick, L. R., Rapanelli, M., Jindachomthong, K., Grant, P., Leckman, J. F., Swedo, S., Williams, K., & Pittenger, C. (2018). Differential binding of antibodies in PANDAS patients to cholinergic interneurons in the striatum. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 69, 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2017.12.004

Grant, J. E., & Chamberlain, S. R. (2020). Exploring the neurobiology of OCD: clinical implications. The Psychiatric Times, 2020, exploring-neurobiology-ocd-clinical-implications. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7334048/

McGeachy, M. J., Cua, D. J., & Gaffen, S. L. (2019). The IL-17 family of cytokines in health and disease. Immunity, 50(4), 892–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.021

Schnell, A., Littman, D. R., & Kuchroo, V. K. (2023). TH17 cell heterogeneity and its role in tissue inflammation. Nature Immunology, 24(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-022-01387-9

Alahmari, A. (2021). Blood-Brain Barrier Overview: Structural and functional correlation. Neural Plasticity, 2021, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6564585

Castillo, E. F., Zheng, H., Van Cabanlong, C., Dong, F., Luo, Y., Yang, Y., Liu, M., Kao, W. W., & Yang, X. O. (2016). Lumican negatively controls the pathogenicity of murine encephalitic TH17 cells. European Journal of Immunology, 46(12), 2852–2861. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201646507

Milovanovic, J., Arsenijevic, A., Stojanovic, B., Kanjevac, T., Arsenijevic, D., Radosavljevic, G., Milovanovic, M., & Arsenijevic, N. (2020). Interleukin-17 in chronic inflammatory neurological diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 947. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00947

Simonyan, K. (2019). Recent advances in understanding the role of the basal ganglia. F1000Research, 8, 122. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16524.1

Negi, S. S., & Braun, W. (2016). Cross-React: a new structural bioinformatics method for predicting allergen cross-reactivity. Bioinformatics, 33(7), 1014–1020. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw767

Trier, N. H., & Houen, G. (2023). Antibody Cross-Reactivity in Auto-Immune diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(17), 13609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241713609

Menendez, C. M., Zuccolo, J., Swedo, S. E., Reim, S., Richmand, B., Ben-Pazi, H., Kovoor, A., & Cunningham, M. W. (2024). Dopamine receptor autoantibody signaling in infectious sequelae differentiates movement versus neuropsychiatric disorders. JCI Insight, 9(21). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.164762

Dong, M., Chen, G., & Hu, L. (2020). Dopaminergic System Alteration in anxiety and Compulsive Disorders: A Systematic Review of Neuroimaging studies. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 608520. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.608520

Lindahl, M., & Kotaleski, J. H. (2016). Untangling basal ganglia network dynamics and function: Role of dopamine depletion and inhibition investigated in a spiking network model. eNeuro, 3(6), ENEURO.0156-16.2016. https://doi.org/10.1523/eneuro.0156-16.2016

Schultz, W. (2016). Reward functions of the basal ganglia. Journal of Neural Transmission, 123(7), 679–693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-016-1510-0

Cunningham, M. W., & Cox, C. J. (2016). Autoimmunity against dopamine receptors in neuropsychiatric and movement disorders: a review of Sydenham chorea and beyond. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England), 216(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12614

Cooperstock, M. S., Swedo, S. E., Pasternack, M. S., & Murphy, T. K. (2017). Clinical Management of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Part III-Treatment and Prevention of Infections. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology, 27(7), 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2016.0151

Gilbert, D. L. (2019). Inflammation in Tic Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Are PANS and PANDAS a Path Forward? Journal of Child Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073819848635

Horne, M., Woolley, I., & Lau, J. S. (2024). The Use of Long-term Antibiotics for Suppression of Bacterial Infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 79(4), 848-854. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciae302

Frieri, M., Kumar, K., & Boutin, A. (2017). Antibiotic resistance. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 10(4), 369-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2016.08.007

Patangia, D. V., Anthony Ryan, C., Dempsey, E., Paul Ross, R., & Stanton, C. (2022). Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. MicrobiologyOpen, 11(1), e1260. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.1260

Dalakas M. C. (2021). Update on Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Neurology: Modulating Neuro-autoimmunity, Evolving Factors on Efficacy and Dosing and Challenges on Stopping Chronic IVIg Therapy. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 18(4), 2397–2418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-021-01108-4

Melamed, I., Rahman, S., Pein, H., Heffron, M., Frankovich, J., Kreuwel, H., & Mellins, E. D. (2024). IVIG response in pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome correlates with reduction in pro-inflammatory monocytes and neuropsychiatric measures. Frontiers in Immunology, 15, 1383973. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1383973

Leon, J., Hommer, R., Grant, P. et al. Longitudinal outcomes of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27, 637–643 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1077-9

Wilbur, C., Bitnun, A., Kronenberg, S., Laxer, R. M., Levy, D. M., Logan, W. J., Shouldice, M., & Yeh, E. A. (2018). PANDAS/PANS in childhood: Controversies and evidence. Paediatrics & child health, 24(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxy145

Eremija, J., Patel, S., Rice, S., & Daines, M. (2023). Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment improves multiple neuropsychiatric outcomes in patients with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome. Frontiers in pediatrics, 11, 1229150. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1229150

Law, C., & Boisseau, C. L. (2019). Exposure and Response Prevention in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Current Perspectives. Psychology research and behavior management, 12, 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S211117

Hezel, D. M., & Simpson, H. B. (2019). Exposure and response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review and new directions. Indian journal of psychiatry, 61(Suppl 1), S85–S92. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_516_18

Chen, X. M., Zhang, S., & Xu, M. (2025). Integrating behavioral interventions for Tourette's syndrome: Current status and prospective. World journal of psychiatry, 15(3), 99045. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i3.99045

Khan, I., Jaura, T. A., Tukruna, A., Arif, A., Tebha, S. S., Nasir, S., Mukherjee, D., Masroor, N., & Yosufi, A. (2023). Use of Selective Alternative Therapies for Treatment of OCD. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 19, 721–732. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S403997

Salm, S., Rutz, J., van den Akker, M., Blaheta, R. A., & Bachmeier, B. E. (2023). Current state of research on the clinical benefits of herbal medicines for non-life-threatening ailments. Frontiers in pharmacology, 14, 1234701. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1234701

Zhao, Q., Hu, Y., Yan, Y., Song, X., Yu, J., Wang, W., Zhou, S., Su, X., Bloch, M. H., Leckman, J. F., Chen, Y., & Sun, H. (2024). The effects of Shaoma Zhijing granules and its main components on Tourette syndrome. Phytomedicine, 129, 155686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155686

Alharthi, M. S. (2025). A narrative review of Phase III and IV clinical trials for the pharmacological treatment of Tourette's syndrome in children, adults, and older adults. Medicine, 104(23), e42760. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000042760

Quezada, J., & Coffman, K. A. (2018). Current Approaches and New Developments in the Pharmacological Management of Tourette Syndrome. CNS drugs, 32(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-017-0486-0

van Roessel, P. J., Grassi, G., Aboujaoude, E. N., Menchón, J. M., Van Ameringen, M., & Rodríguez, C. I. (2023). Treatment-resistant OCD: Pharmacotherapies in adults. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 120, 152352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152352

Celik, G., Taş, D., Tahiroglu, A., Avci, A., Yuksel, B., & Cam, P. (2016). Vitamin D Deficiency in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Patients with Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections: A Case Control Study. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 53(1), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2015.8763

Kuygun Karci, C., & Gul Celik, G. (2020). Nutritional and herbal supplements in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. General psychiatry, 33(2), e100159. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2019-100159

Sathvika, V. P., Subhas, P. G., Bhattacharjee, D., Koppad, V. N., Samrat, U., Karibasappa, S. B., & Sagar, K. M. (2024). Review of Case Study Results: Assessing the Effectiveness of Curcumin, St. John’s Wort, Valerian Root, Milk Thistle, and Ashwagandha in the Intervention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Drugs and Drug Candidates, 3(4), 838-859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ddc3040047

Wimalawansa S. J. (2023). Physiological Basis for Using Vitamin D to Improve Health. Biomedicines, 11(6), 1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061542

Wang, S., Zhang, X., Ding, Y., Wang, Y., Wu, C., Lu, S., & Fang, J. (2024). From OCD Symptoms to Sleep Disorders: The Crucial Role of Vitamin B12. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 20, 2193–2201. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S489021

Algin, S., Ahmed, T., Reza, M. M., Akter, A., Tanzilla, N. J., Haq, M. A., Ahmad, R., Mehta, M., & Haque, M. (2025). Evaluating Treatment Outcomes of Vitamin B12 and Folic Acid Supplementation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Patients With Deficiencies: A Comparative Analysis. Cureus, 17(4), e82420. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.82420

Dominguez, L. J., Farruggia, M., Veronese, N., & Barbagallo, M. (2021). Vitamin D Sources, Metabolism, and Deficiency: Available Compounds and Guidelines for Its Treatment. Metabolites, 11(4), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11040255

Obeid, R., Heil, S. G., Verhoeven, M. M. A., van den Heuvel, E. G. H. M., de Groot, L. C. P. G. M., & Eussen, S. J. P. M. (2019). Vitamin B12 Intake From Animal Foods, Biomarkers, and Health Aspects. Frontiers in nutrition, 6, 93. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2019.00093

Esalatmanesh, S., Biuseh, M., Noorbala, A. A., Mostafavi, S. A., Rezaei, F., Mesgarpour, B., Mohammadinejad, P., & Akhondzadeh, S. (2017). Comparison of Saffron and Fluvoxamine in the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Iranian journal of psychiatry, 12(3), 154–162.

Han, S., Cao, Y., Wu, X., Xu, J., Nie, Z., & Qiu, Y. (2024). New Horizons for the study of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and its active ingredients in the management of neurological and psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of clinical evidence and mechanisms. Phytotherapy Research, 38(5), 2276–2302. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.8110

Kell, G., Rao, A., Beccaria, G., Clayton, P., Inarejos-García, A. M., & Prodanov, M. (2017). AFFRON® a novel saffron extract (Crocus sativus L.) improves mood in healthy adults over 4 weeks in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 33, 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2017.06.001

Zheng, Y., Zhang, Z.-J., Han, X.-M., Ding, Y., Chen, Y.-Y., Wang, X.-F., Wei, X.-W., Wang, M.-J., Chen, Y., Nie, Z.-H., Zhao, M., & Zheng, X.-X. (2015). A proprietary herbal medicine (5-Ling Granule) for Tourette syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 57(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12432

Li, X., He, Y., Zeng, P., Liu, Y., Zhang, M., Hao, C., Wang, H., Lv, Z., & Zhang, L. (2019). Molecular basis for Poria cocos mushroom polysaccharide used as an antitumour drug in China. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 23(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13564

Yan, B., Shen, M., Fang, J., Wei, D., & Qin, L. (2018). Advancement in the chemical analysis of Paeoniae Radix (shaoyao). Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 160, 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2018.08.009

Gilbert DL. Inflammation in Tic Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Are PANS and PANDAS a Path Forward? Journal of Child Neurology. 2019;34(10):598-611. doi:10.1177/0883073819848635

Colvin, M. K., Erwin, S., Alluri, P. R., Laffer, A., Pasquariello, K., & Williams, K. A. (2021). Cognitive, graphomotor, and psychosocial challenges in pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (pandas). The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 33(2), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20030065