Compassion Divided: How Racial Bias Impacts Empathy

Yasmine Alami

Illustrations by Ella Manhardt

‘You ask, ‘Where do I sign in?’ You get dismissed. They’re like, ‘I’m on the phone,’ or whatever. Then you turn around for a second and you have a Caucasian that comes in and they are like, ‘Hello, how can we help you?’ [1].

Racial bias has far-reaching effects throughout society and is especially prevalent in medical settings [2]. Documented patient experiences show us how these biases manifest for different marginalized groups [1]. When Black women were asked about their experiences with the health care system, one individual spoke about how doctors continuously ignored her symptoms, brushing past her as if she didn’t exist [1]. Other instances have occurred where Black women were told they must leave the hospital right after surgery, despite expressing their pain [1]. Similarly, a Latino man spoke out about his experience in an emergency room, where, upon arrival, he was immediately spoken to in Spanish, solely based on his Latino features [1]. Upon revealing he was a doctor with health insurance, medical professionals surrounded him, eager to treat the sick doctor [1]. Later, he retold the story, noting how shocked the nurse was, as the ‘color on her face went completely white, like whiter than it already was’ [1]. These experiences of mistreatment, neglect, or even something as simple as an assumed narrative are derived from subconscious bias [3]. This form of discrimination is known as implicit bias and heavily impacts minorities, immigrants, women, and children [4]. Specifically, racial biases can have a profound effect on our ability to empathize with others, leading to unequal treatment from patient to patient, with racial minorities facing medical neglect, which forces them to self-advocate or chase down health care professionals in order to be treated [1,5]. Implicit bias greatly affects empathy and can be detrimental in a clinical setting, creating unequal medical treatment [5].

Proactive in a Prosocial World: How Empathy Manifests

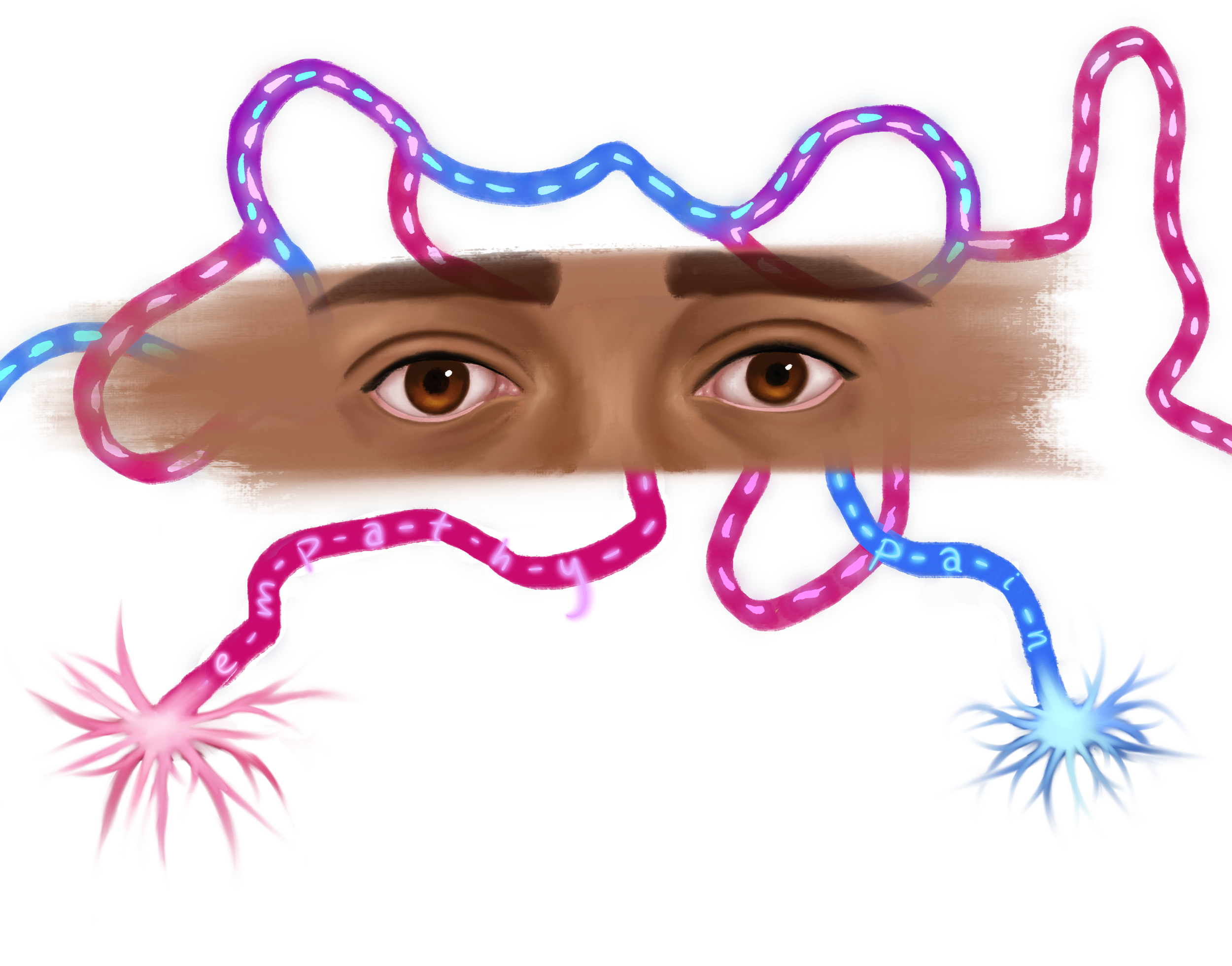

Empathy is the ability to understand other individuals' emotional and psychological states — to feel what another person feels [6]. However, empathy is more than just a feeling; it informs our actions and decisions [7]. When we perceive others to be in some form of distress, our empathy motivates us to perform voluntary actions to help them, creating more caring and selfless environments [6, 8]. An action performed to help another is known as a prosocial behavior and typically improves one’s own feelings of mood and self-worth [8]. A subtype of prosocial behavior includes altruistic behaviors, which are completely selfless actions [8]. Altruistic behaviors are performed expecting no personal gain, even ignoring personal consequences to perform the selfless act [9, 10]. While prosocial behaviors can be motivated by positive feelings of self-worth, altruistic behaviors may result in a similar boost in self-worth, but these feelings are not motivators behind altruistic actions [11]. Prosocial behavior and altruism are fundamental for the creation of caring environments, especially in healthcare [12]. Ultimately, when observing someone in distress, our empathy responses are ignited, catalyzing prosocial and sometimes altruistic behaviors [6]. Therefore, as empathy is impacted by biases, so are the behaviors that are essential in helping others [13]. In a medical environment, health workers' ability to empathize with their patients is essential for providing adequate care [14]. When physicians identify with a patient’s emotional state, it enables them to see the patient as a human being and prioritize the patient’s well-being, values, and dignity [15, 16].

Something to Reflect on: Understanding Empathy in the Brain

Empathetic responses are formed by an intricate neural mechanism composed of different neural networks within the brain [17]. These networks are complex systems made of neurons — which are specialized cells that communicate through chemical and electrical signals within the nervous system [18]. Different networks are present across the brain and have different purposes. Multiple networks of neurons reside in the somatosensory cortex, a section of the brain that processes sensory information in tandem with other brain regions, such as the amygdala and the insula [19]. While the amygdala is involved in emotional processing, the insula is involved in the perception and interpretation of social cues [19]. Specifically, the mirror neuron system, within the somatosensory cortex, is a system implicated in understanding the actions of others — allowing an individual to ‘feel what another person feels’ [20]. Activity in the mirror neuron system increases both when observing an action performed by someone else and when performing the same action [21]. Observing other people’s pain automatically activates the mirror neuron system in the somatosensory cortex because the mirror neuron system is activated along the same networks as an individual personally experiencing pain [19]. The mirror neuron system is intricately connected to the mentalizing network, a network involved in interpreting and responding to others' thoughts, perceptions, and experiences [19, 22]. Communication between the mirror neurons within the somatosensory system and the mentalizing network allows the brain to interpret the experience of others’ pain to better understand the situation and form an appropriate response [19]. Stronger communication enables the processing of understanding other individuals, further providing the foundation of the underlying mechanisms of pain empathy [23].

The ability to empathize with pain is further contributed to other central brain regions: the anterior insula cortex (AIC) — a region involved in the integration of internal bodily sensations, emotions, and cognitive processing — and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) — a region implicated in pain perception and emotional regulation [24, 25, 26]. Overlapping activity in neural networks in the AIC and ACC subsequently lays a foundation for pain-based empathy, allowing individuals to consciously perceive the pain of others based on their emotional states and other cues without directly experiencing the pain themselves [24, 27]. Specifically, the AIC communicates with a subregion of the ACC known as the anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC), which is involved in understanding information, formulating responses to these events, and empathizing with others' pain [26, 28]. However, activity in these regions is impacted by multiple factors, including subconscious bias [29].

The Ins and Outs of Racial Bias

The activation of the aMCC can be influenced by different forms of implicit biases, including ingroup and outgroup biases [29]. Individuals tend to favor people they consider part of their own social group — a behavior known as ‘ingroup bias’ [29, 30]. Ingroup bias can be shaped by social categories such as race, ethnicity, or even sports team affiliations [30]. Say you are watching your favorite soccer team, and a player on the opposing team gets injured. Since the player is part of the outgroup, you would feel less empathy towards them [31]. Whereas if a player on your team gets injured, you would feel more empathy towards them because they are part of the ingroup [30]. Ingroup bias has consequences that reach beyond sports rivalries; ingroup bias affects how we view individuals of other races [32]. ACC activity is increased when observing pain in own-race individuals compared to other-race individuals [29]. Such bias is known as racial ingroup bias, where one views people of the same race as their ingroup — on the same team [32]. Implicit bias shapes this response depending on the situation; individuals with higher bias exhibit greater ACC activation for own-race individuals regardless of whether there is pain present [29]. The difference in ACC activation to ingroup vs. outgroup members suggests that the ACC plays a key role in empathetic processing that may also be heavily influenced by racial and other social factors [29].

Under Assessment: Empathy and Racism in Clinical Settings

It is crucial to understand that empathy is influenced by ingroup and outgroup biases, which, in clinical settings, contribute to inequalities within patient care [30]. Racial empathy is shaped by social group membership — namely, by who is perceived as an ingroup or outgroup member [30]. Social group membership influences neural activation related to empathy, where individuals have stronger neural responses for same-race pain compared to other-race pain [30]. When witnessing others in pain, people connect more deeply and feel greater emotional understanding towards same-race individuals [33]. Thus, in clinical settings, physicians’ empathetic responses are shaped by their implicit biases, potentially leading them to favor patients of the same race and provide lower-quality care to other races; such bias is seen when Black patients are prescribed insufficient pain medication by White doctors [34, 35]. Unequal treatment also can affect patient-physician communication across the board, as communication, influenced by bias, systematically allows more engagement with White patients [29]. Implicit bias correlates with unconscious differences in treatment, decisions, and judgments that contribute to healthcare disparities [14]. Therefore, pain assessment, treatment recommendations, and prioritization of attention and care, as well as a patient's willingness to share concerns surrounding their health, are not given the same attention and care that same-race patients receive [1, 14, 36].

The impact of reduced empathy further extends to systemic disparities, creating a lack of trust between patients and physicians, causing an overall harmful psychological impact [37, 38, 39]. Systemic racism — racial inequalities built into societal structures and opportunities — is reinforced through the normalization of decreased empathy caused by racial bias, alienating minority patients who feel less empathy from providers [37, 38, 40]. Further, physicians are less likely to communicate with or understand minority patients, due to said lack of empathy, reinforcing these patterns of inequitable care [37]. In one instance, a Pakistani patient in the US often felt unwanted, claiming that ‘those [patients] who cannot speak English get into trouble, and they get a bit bullied as well’ [37]. Similar stories have been seen across the US, where minority groups felt they were treated harshly, given less priority, and experienced hostile conversations [37]. This mistreatment leads to a lack of trust between patients and health care providers [37]. Moreover, physicians who believe racial stereotypes further perpetuate this cycle of mistreatment and mistrust [41]. For example, some providers think Black patients are less likely to follow medical instructions than their White counterparts, and therefore may not provide adequate medical information to Black patients in the first place [38]. Consequently, Black patients are significantly less likely to be notified of their diagnosis than White patients [38]. Implicit bias often leads physicians to favor White patients over Black patients, which can lead to detrimental effects on the mental and physical health of minority patients [39]. Racial discrimination can be a chronic stressor, often linked to an increased risk for depression, anxiety, and psychiatric disorders [39]. Discrimination can further lead to self-condemnation and exclusion from others, causing individuals to feel on edge when they enter the patient setting as they anticipate discrimination [39]. Ultimately, health care providers’ racial and implicit bias lead to a lack of empathetic behaviors that result in not only diminished care but increased risk for additional health concerns [39].

Cracks in the Foundation: Systemic Issues

Investigating the neural underpinnings of empathy is essential in clinical practice as it provides insight into racial disparities within healthcare [36]. Implicit bias also expands to social class, affecting the treatment of individuals across social classes [42]. In addition to pre-existing financial barriers to treatment, patients with lower socio-economic status often face lower standards of care from providers with implicit bias [42]. Bias towards people of lower socio-economic status can manifest as health care providers offering lower quality treatment or viewing low-income patients as either incapable or noncompliant with medication instructions [42]. However, because medication may be prohibitively expensive for individuals with low incomes, compliance with medical treatment is inherently unattainable [43]. Mistreatment of patients based on their low socioeconomic status also leads to lower life expectancy, as physicians often misinterpret patient needs, basing physician-patient communication on preconceived stereotypes [44]. Reduced empathy from implicit racial bias further contributes to healthcare inequality for individuals with low income, as care becomes less equitable and accessible [44, 45]. African American patients on Medicare received worse medical care than Caucasian patients on Medicare who had the same condition [45]. Low-quality care makes patients question whether they should seek medical attention, forcing them to struggle with their health issues alone — including dealing with a lack of treatment, potential disease progression, and having poor health overall [46].

The effects of racial bias expand to medical education, where Black and Latine student trainees are often averse to challenging their resident or attending, who are authoritative figures in the medical hierarchy [47]. Some students are concerned with being misjudged, having experienced microaggressions previously during their training [47]. In a severe example, one group of students had concerns about their non-Black resident, who treated a Black patient with sickle cell disease, all while the patient continued to experience pain [47]. The non-Black resident acted as though the Black patient’s pain was made up [47]. The Black and Latine students struggled with advocating for their Black patient, worried they may be at risk of discrimination themselves [47]. Furthermore, while race has no scientific basis, medical education still harbors the idea that people are biologically different based on their ethnicity [48]. This false idea continues to be used within teaching practices, perpetuating unequal treatment within the health care system [48].

Pathways for Empathy in a Divided World

Total elimination of bias within clinical settings is unrealistic [1]. However, recognizing these treatment disparities highlights the need for intervention aimed at reducing bias and improving empathetic responses in healthcare. Perspective taking, a method that has a mindfulness-based approach, allows individuals to consider how others think and feel [49]. Understanding others from a different perspective allows for an increase in empathy for individuals of other races by more strongly identifying with them, effectively reducing bias in decision-making [50]. In addition, exposure to outgroup members through interracial and sociocultural interactions — spending time with people from different racial or social groups — can also lead to stronger empathetic neural responses for pain [51]. There are many ways we are taught to discriminate; some are benign, like favoring one sports team over another, and others are far more insidious, like racial bias. There are also many ways that we can learn to overcome our biases and practice empathy for members of both ingroups and outgroups. Implementing training systems and real-world experience can help mitigate implicit biases in healthcare and move towards providing equitable care for all [5, 51].

References

Gonzalez, C. M., Deno, M. L., Kintzer, E., Marantz, P. R., Lypson, M. L., & McKee, M. D. (2018). Patient perspectives on racial and ethnic implicit bias in clinical encounters: Implications for curriculum development. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(9), 1669–1675.

Ramsoondar, N., Anawati, A., & Cameron, E. (2023). Racism as a determinant of health and health care: Rapid evidence narrative from the SAFE for Health Institutions project. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 69(9), 594–598. https://doi.org/10.46747/cfp.6909594

Thompson, R. V., Barbee, J., Stancato, N., & Pfeil, S. (2025). The effectiveness of implicit bias training for simulated participants. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 105, 101781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2025.101781

Dahlen, B., McGraw, R., & Vora, S. (2024). Evaluation of simulation-based intervention for implicit bias mitigation: A response to systemic racism. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 95, 101596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2024.101596

Mei, S., Deng, Y., Zheng, G., & Han, S. (2025). Reducing racial ingroup biases in empathy and altruistic decision-making by shifting racial identification. Science Advances, 11(17). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt6207

Decety, J., Bartal, I. B.-A., Uzefovsky, F., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2016). Empathy as a driver of prosocial behaviour: Highly conserved neurobehavioural mechanisms across species. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1686), 20150077. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0077

Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2014). Friends or Foes: Is Empathy Necessary for Moral Behavior?. Perspectives on psychological science : a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 9(5), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614545130

Filkowski, M., Cochran, R. N., & Haas, B. (2016). Altruistic behavior: Mapping responses in the brain. Neuroscience and Neuroeconomics, Volume 5, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.2147/nan.s87718

Bhuvana, M. L., Pavithra, M. B., & Suresha, D. S. (2021). Altruism, an attitude of unselfish concern for others - an analytical cross sectional study among the Medical and Engineering students in Bangalore. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 10(2), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_834_20

Pfattheicher, S., Nielsen, Y. A., & Thielmann, I. (2022). Prosocial behavior and altruism: A review of concepts and definitions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.021

Weiss-Sidi, M., & Riemer, H. (2023). Help others-be happy? The effect of altruistic behavior on happiness across cultures. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1156661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1156661

Hart R. (2024). Prosocial behaviors at work: Key concepts, measures, interventions, antecedents, and outcomes. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 14(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010078

Fowler, Z., Law, K. F., & Gaesser, B. (2021). Against empathy bias: The moral value of equitable empathy. Psychological Science, 32(5), 766–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620979965

Moudatsou, M., Stavropoulou, A., Philalithis, A., & Koukouli, S. (2020). The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 8(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010026

Des Ordons, A. L., De Groot, J. M., Rosenal, T., Viceer, N., & Nixon, L. (2018). How clinicians integrate humanism in their clinical workplace—‘just trying to put myself in their human being shoes.’ Perspectives on Medical Education, 7(5), 318–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0455-4

Thibault G. E. (2019). Humanism in medicine: What does it mean and why is it more important than ever?. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 94(8), 1074–1077. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002796

Ebisch, S. J. H., Scalabrini, A., Northoff, G., Mucci, C., Sergi, M. R., Saggino, A., Aquino, A., Alparone, F. R., Perrucci, M. G., Gallese, V., & Di Plinio, S. (2022). Intrinsic shapes of empathy: Functional brain network topology encodes intersubjective experience and awareness traits. Brain Sciences, 12(4), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12040477

Bile, A. (2024). Solitonic neural networks. Machine Intelligence for Materials Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48655-5

Zhang, P., Ding, L., Wang, M., & Qiu, S. (2025). Neural mechanisms of physical and social pain empathy: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of fmri studies. Cerebral Cortex, 35(8). https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaf227

Lamm, C., & Majdandžić, J. (2015). The role of shared neural activations, mirror neurons, and morality in empathy – a critical comment. Neuroscience Research, 90, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2014.10.008

Patel, J. (2024). Advances in the study of mirror neurons and their impact on neuroscience: An Editorial. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.61299

Fu, X., Hung, A., de Silva, A. D., Busch, T., Mattson, W. I., Hoskinson, K. R., Taylor, H. G., & Nelson, E. E. (2022). Development of the mentalizing network structures and theory of mind in extremely preterm youth. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(11), 977–985. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsac027

Wagner, I. C., Rütgen, M., & Lamm, C. (2020). Pattern similarity and connectivity of hippocampal-neocortical regions support empathy for pain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa045

Fallon, N., Roberts, C., & Stancak, A. (2020). Shared and distinct functional networks for empathy and pain processing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of fmri studies. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(7), 709–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa090

Cox, S. S., Kearns, A. M., Woods, S. K., Brown, B. J., Brown, S. J., & Reichel, C. M. (2022). The role of the anterior insula during targeted helping behavior in male rats. Scientific Reports, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07365-3

Namkung, H., Kim, S. H., & Sawa, A. (2017). The Insula: An underestimated brain area in clinical neuroscience, psychiatry, and neurology. Trends in Neurosciences, 40(4), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2017.02.002

Xiang, Y., Wang, Y., Gao, S., Zhang, X., & Cui, R. (2018). Neural mechanisms with respect to different paradigms and relevant regulatory factors in empathy for pain. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00507

Chen, W. G., Schloesser, D., Arensdorf, A. M., Simmons, J. M., Cui, C., Valentino, R., Gnadt, J. W., Nielsen, L., Hillaire-Clarke, C. St., Spruance, V., Horowitz, T. S., Vallejo, Y. F., & Langevin, H. M. (2021). The emerging science of interoception: Sensing, integrating, interpreting, and regulating signals within the self. Trends in Neurosciences, 44(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2020.10.007

Shen, F., Hu, Y., Fan, M., Wang, H., & Wang, Z. (2018). Racial bias in neural response for pain is modulated by minimal group. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00661

Han, S. (2018). Neurocognitive basis of racial ingroup bias in empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(5), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.02.013

Arceneaux, K. (2017). Anxiety reduces empathy toward outgroup members but not in ingroup members. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 4(1), 68–80. doi:10.1017/XPS.2017.12

Yu, J., Wang, Y., Yu, J., & Zeng, J. (2021). Racial ingroup bias and efficiency consideration influence distributive decisions: A dynamic analysis of Time Domain and time frequency. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.630811

Pang, C., Zhou, Y., & Han, S. (2024). Temporal unfolding of racial ingroup bias in neural responses to perceived dynamic pain in others. Neuroscience Bulletin, 40(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-023-01102-0

Rojas, C. R., Badolato, G. M., Marshall, J., Boyle, M., Zimber, D., Sabin, J., Chamberlain, J. M., Hinds, P., Schultz, T. R., Bost, J. E., McCarter, R., & Goyal, M. K. (2025). Inequities in timeliness of pain management of fractures in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics Open Science, 1(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/pedsos.2025-000617

Vela, M. B., Erondu, A. I., Smith, N. A., Peek, M. E., Woodruff, J. N., & Chin, M. H. (2022). Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: Evidence and research needs. Annual Review of Public Health, 43(1), 477–501. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-103528

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113

Sim, W., Lim, W. H., Ng, C. H., Chin, Y. H., Yaow, C. Y., Cheong, C. W., Khoo, C. M., Samarasekera, D. D., Devi, M. K., & Chong, C. S. (2021). The perspectives of health professionals and patients on racism in Healthcare: A qualitative systematic review. PLOS ONE, 16(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255936

Schut, R. A. (2021). Racial disparities in provider-patient communication of incidental medical findings. Social Science & Medicine, 277, 113901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113901

Williams, D. R. (2018). Stress and the mental health of populations of color: Advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(4), 466–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146518814251

Banaji, M. R., Fiske, S. T., & Massey, D. S. (2021). Systemic racism: Individuals and interactions, institutions and Society. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00349-3

Sorice, V., Mortimore, G., Faghy, M., Sorice, R., & Tegally, D. (2025). The perpetual cycle of racial bias in healthcare and Healthcare Education: A systematic review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-025-02417-6

Atkins, N., & Mukhida, K. (2022). The relationship between patients’ income and education and their access to pharmacological chronic pain management: A scoping review. Canadian Journal of Pain, 6(1), 142–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/24740527.2022.2104699

Fernandez-Lazaro, C. I., Adams, D. P., Fernandez-Lazaro, D., Garcia-González, J. M., Caballero-Garcia, A., & Miron-Canelo, J. A. (2019b). Medication adherence and barriers among low-income, uninsured patients with multiple chronic conditions. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(6), 744–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.09.006

Job, C., Adenipekun, B., Cleves, A., & Samuriwo, R. (2022). Health professional’s implicit bias of adult patients with low socioeconomic status (SES) and its effects on clinical decision-making: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 12(12). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059837

Yearby, R. (2018). Racial disparities in health status and access to healthcare: The continuation of inequality in the United States due to structural racism. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 77(3–4), 1113–1152. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12230

Campbell, C. N. (2025). Healthcare inequities and healthcare providers: We are part of the problem. International Journal for Equity in Health, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-025-02464-9

Plaisime, M. V., Jipguep-Akhtar, M.-C., & Belcher, H. M. E. (2023). ‘white people are the default’: A qualitative analysis of medical trainees’ perceptions of cultural competency, medical culture, and racial bias. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health, 4, 100312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100312

Mouhab, A., Radjack, R., Moro, M. R., & Lambert, M. (2024). Racial biases in clinical practice and medical education: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06119-1

Beck, C., García, Y., & Catagnus, R. (2023). Effects of perspective taking and values consistency in reducing implicit racial bias. Universitas Psychologica, 21. https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.upsy21.eptv

Gutsell, J. N., Simon, J. C., & Jiang, Y. (2020). Perspective taking reduces group biases in sensorimotor resonance. Cortex, 131, 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.04.037

Zhou, Y., Pang, C., Pu, Y., & Han, S. (2022). Racial outgroup favoritism in neural responses to others’ pain emerges during sociocultural interactions. Neuropsychologia, 174, 108321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2022.108321