Picture Perfect: The New Reality of Rehabilitation is Virtual

Sushama Gadiyaram

Illustrations by Alexandra Tapia

What happens when fundamental abilities, such as walking, speaking, and remembering, suddenly disappear after a neurological injury? For individuals suffering from stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), or Parkinson’s Disease (PD), the loss of these essential skills transforms everyday life into a series of obstacles [1]. Individuals may turn to neurorehabilitation — therapeutic practices used to restore lost functions or help the brain adapt to lasting damage [2]. Traditional neurorehabilitation usually involves repetitive cognitive drills, structured physical training, and various therapist-guided exercises, which all aim to retrain the brain through consistent practice [3]. While clinically effective, many individuals struggle with decreased engagement, slower progress, and repetitiveness of traditional rehabilitation tasks, which can undermine recovery [4]. This is where virtual reality (VR) offers a completely new advantage. VR refers to immersive, digitally generated environments that allow individuals to interact with both realistic or fictional virtual worlds using visual, auditory, and sensory feedback [5]. Compared to traditional therapy at an office, VR can simulate everyday activities such as navigating a busy grocery store, preparing a meal, and driving to work [6]. In these guided and safe simulations, VR excites cognitive, motor, and emotional neural pathways that are key for long-term neurological changes [6]. Immersive and interactive therapeutic approaches like VR-based therapies are very effective as they increase feedback, consistency, and motivation [7]. VR therapy has a promising future in neurorehabilitation, offering innovative ways to restore cognitive and motor function through the power of generative images and immersive worlds [8].

Picture This: VR as a Tool for Cognitive Rehabilitation

VR is a valuable tool for improving impaired cognitive abilities from brain injury or cognitive decline [9]. Cognitive abilities can be thought of as a mental toolkit that allows us to take in information, understand it, and respond appropriately [10]. They are the foundation of how we think and interact with the world, including abilities such as attention, memory, and problem-solving [11, 12]. When cognitive skills are disrupted, neurorehabilitation is required in order to get them working properly again [11]. VR offers an exciting alternative to traditional cognitive therapy, which can be slow due to inconsistency or a lack of engagement [13]. By simulating real-world situations, VR allows the brain to practice cognitive abilities in dynamic and meaningful ways [6]. Think of VR as a flight simulator: a controlled environment that enables users to safely gain a realistic experience flying and maneuvering planes that would otherwise be impossible [14]. Therapists are therefore able to recommend VR regimens that offer functions unavailable in reality, such as seeing a virtual version of one's body from a third-person perspective or instantly teleporting to a brand new environment [6].

In addition, the highly controllable nature of VR allows it to be tailored to the specific conditions or interests of individuals [7, 15]. The cognitive decline experienced by a person with PD, for example, differs from the cognitive impairments of a person suffering from a TBI [16]. With PD, there is an overall decline in cognitive function, affecting abilities like problem-solving, whereas a TBI often involves attention impairment or localized brain damage [17, 18]. Using VR, an individual with PD can solve puzzles, fingerpaint, or switch between Earth and zero gravity simulations to train the brain to handle novel demands [19]. On the other hand, VR can improve TBI symptoms by challenging individuals to perform important tasks such as planning a bus route or evacuating a burning building [20].

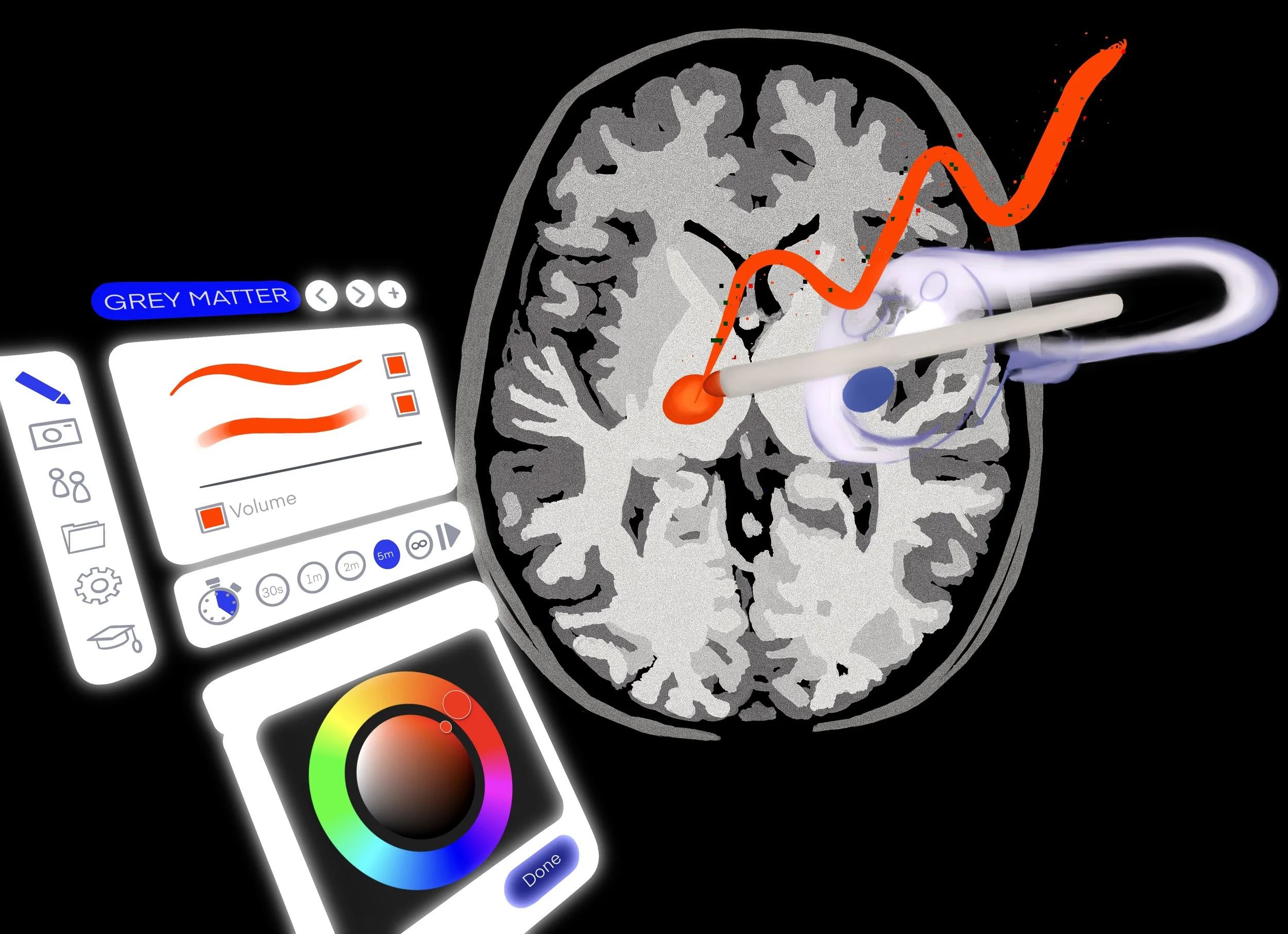

Treatment of cognitive deficits with VR results in tangible changes in both the brain’s structure and activity [7]. This impact is structurally visible in increased volume of gray matter — brain tissue composed primarily of cell bodies and neural circuits that foster cognitive functions — following long-term VR therapy [21, 22]. Along with structural changes, there are changes in brain activity that can be measured with electroencephalography (EEG), a technology that monitors the electrical signals in the brain and determines how different brain regions activate and interact with one another, correlating with the recovery of cognitive function [23, 24]. Specifically, beta-wave activity — a type of electrical signal measured with an EEG that reflects active thinking and alertness — tends to increase when these individuals participate in VR tasks that require attention, memory, or quick decision-making [25, 26]. These changes in the brain correlate with subjective reports: VR makes it easier to focus, recall information, and solve complex problems [27]. Furthermore, individuals who train with VR often demonstrate an improvement in cognitive skills that carry over into real-life scenarios [28]. By creating experiences that are both challenging and enjoyable, VR creates an environment where the brain can restore impaired cognitive skills, which is foundational for long-term functional improvements [13].

Moving Pictures: VR as a Tool for Motor Rehabilitation

VR technology is also a valuable tool for enhancing motor functions, the abilities that control movement, balance, and coordination [29]. Traditionally, individuals in pain or experiencing limited motor skills may turn to physical therapy (PT) for physical rehabilitation [30]. Traditional PT helps individuals create new motor pathways effectively or strengthen existing ones [31]. Motor pathways refer to a system of neural circuits — the web of communication between neurons, or brain cells — that transmit signals from the brain to the muscles, enabling movement and controlling posture, balance, and reflexes [32]. When these motor circuits are weakened, by injury or disease, an individual experiences limited motor function [33, 34]. VR can better address these deficits by immersing individuals in a simulated world and actively engaging the same brain regions used for real-world movement [31]. Furthermore, traditional PT often involves physical exercises in a contained environment, making the experience feel clinical or overly repetitive [3]. Conversely, VR’s limitless visuals allow individuals to experience physical therapy in various environments [35]. With VR-based therapy as a compelling alternative, the familiar PT office falls away as an individual puts on a VR headset. Engagement is heightened in this new world of therapy, where one could walk across a virtual canyon or navigate a busy intersection all from the safety of the PT office [36]. In this way, VR provides individuals with motor loss a diverse and exciting environment to pursue rehabilitation [31].

The efficacy of VR training depends heavily on the combination of physical effort with instant, multi-sensory guidance [21]. Immersive VR tasks enhance motor function by transforming abstract movement into visual and sensory feedback that informs coordination [21]. For example, during a task like lifting one’s arm to a specific height, the VR environment can instantly offer feedback in multisensory cues: a visual score will increase, and a positive tone will sound [37]. Immediate feedback is paramount to long-term learning in the brain because it allows the brain to quickly recognize errors and correct movement patterns, strengthening neural circuits [7]. Strengthening motor pathways can be facilitated by many types of VR motor function therapy, including virtual mirror therapy and touch-enhanced feedback [38, 39]. Virtual mirror therapy enables motor learning by displaying a real-time reflection of one’s impaired limb [40]. By creating the illusion of a fully functioning limb through visual feedback, this technique activates the motor cortex — the brain region primarily responsible for motor coordination — and strengthens the connection between visual and motor processing [38]. The mirroring essentially tricks the brain into reactivating dormant pathways and restoring motor function [38]. Furthermore, some VR models include touch enhancement, which allows the individual to experience the sensation of other objects, such as simulating the weight of a coffee cup [39]. This version of highly engaging, feedback-rich rehabilitation effectively ‘sets the scene,’ allowing individuals to have a fulfilling experience, even if it’s virtual [35].

Immersive VR: Getting the Picture

Recall the possibility of walking across a virtual canyon: the emotional excitement of this novel experience highlights VR’s unique capability to activate the brain's reward and motivation systems [15, 41]. When interacting with an object or completing a task in VR, the brain still responds as if the experience is real [42, 43]. These experiences can be expanded to positive feelings of success; for example, winning a boxing game in VR can trigger genuine physical and emotional reactions of success and achievement [42, 43]. VR has been shown to trigger the release of the reward chemical dopamine, activating the reward pathways that influence us to repeat the rewarding activity [44, 45]. Dopamine release is critical for motivation, learning, and the rewiring of the brain — a process known as dopamine-modulated neuroplasticity [45, 46]. All forms of neurorehabilitation rely on neuroplasticity, which is the brain's ability to reshape its own wiring by strengthening existing connections and building new ones [46]. Neuroplasticity facilitates the learning of new skills, recovery of lost functions, and adaptation to changing physical or cognitive demands. Hence, neuroplasticity is extremely beneficial for neurorehabilitation because it facilitates motor learning, increases motivation, and helps restore damaged neural circuits. By activating these reward pathways and stimulating the motor cortex through feedback-driven tasks, neuroplasticity increases — new neural connections are formed, some are strengthened, and others are rewired. This, in turn, leads to both short-term and long-term positive behavioral changes. In the short term, one could experience improved attention, motor control, and task performance; if one continues this VR therapy long term, they could experience cognitive improvement, behavioral adaptations, and emotional resilience. These beneficial effects contribute to a positive feedback loop, where the response to a behavior increases the behavior. Due to these encouraging associations, the individual would continue using VR, increasing the beneficial long-term effects of neurorehabilitation [46].

Crucially, due to novelty and motivational engagement, VR-based rehabilitation can create emotional investment in one’s recovery [47, 48]. A key issue with current neurorehabilitation practices is a lack of motivation and long-term continuation, which is critical for maintaining improved cognitive skills [21, 49]. Motivation can wane due to its emotionally overwhelming nature, its tediousness, or avoidance of pain [49, 50]. Although difficult to maintain, emotional engagement is necessary to reap the positive benefits of rehabilitation by leading individuals to continue, as shown by the high connection between engagement and successful therapeutic results [48, 51]. Emotional engagement further contributes to the formation and strengthening of neural pathways over time by encouraging the individuals to continue therapy, ensuring it takes full effect in the brain [7, 48]. While traditional methods may allow motivation to decrease, VR’s engaging nature increases motivation and can dramatically increase the number of therapeutic exercises an individual completes [7]. VR encourages individuals to stay motivated through emotional engagement, increasing learning and neuroplasticity, and furthering long-term rehabilitation [7].

The Picture of Health: Implementing VR Therapies

VR aids in the strengthening of neural pathways by recreating a feeling of embodiment — the deep connection between the brain, body, and the environment that defines how we experience movement and selfhood [52]. Similar to virtual mirror feedback, embodiment enables individuals to perceive virtual limbs or avatars as part of their own body [53]. The illusion of ownership activates and strengthens previously weakened neural pathways that support motor and sensory functions [53]. For example, a person recovering from a stroke may see their virtual leg move smoothly in coordination with their thoughts, and over time, the brain can begin to regain function in their physical leg [54]. While PT is limited to the external repetition of movement, VR can simulate embodiment by combining visual displays, sensorimotor feedback, and emotional engagement to stimulate the neural circuits involved in body control and awareness [55].

Furthermore, VR therapy can be applied to a variety of neurological conditions [56]. People with PD experience a loss of dopamine-producing neurons, leading to disruption of the brain’s motor functions [57]. For these individuals, VR can significantly improve gait, balance, and coordination while also encouraging the brain to rewire itself through rewarding and repetitive tasks [56, 58]. Moreover, VR-based rehabilitation can increase dopamine release from remaining neurons and reinforce adaptive neural networks, which may help slow the progression of motor or cognitive deficits seen with PD [15, 59]. The adaptability of VR allows exercises to be modified based on individual performance, pushing participants to achieve cognitive engagement and promoting recovery [15, 60]. This VR technology is generally safe for continuous use, can be adapted for several age groups, and is much more accessible than traditional therapy [51]. Additionally, the reduced rehabilitation costs and flexibility of VR make it more convenient than conventional therapy [51].

The Big Picture: The Future of VR in Neurorehabilitation

VR-based rehabilitation has the power to assist disrupted relationships between the brain and body by using the brain’s capacity for plasticity [6, 8]. While traditional therapies have been indispensable, VR introduces a method that combines embodiment, engagement, and personalization that is difficult to replicate in a clinical setting [14, 15]. Although VR-based therapy isn’t the only path to recovery, it is an evidence-based, rapidly evolving technology that should be more widely available to all individuals who might benefit from its therapeutic strengths [35]. VR illustrates the ties between cognition, movement, and perception, which is especially crucial for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD or injuries that disrupt the brain in multiple ways [7]. With VR, the motions of PT can now be embedded in an emotionally rich scenario such as catching a firefly in a forest, playing beautiful music on a piano, or throwing pottery on a wheel [15, 41]. The possibilities with VR are essentially limitless. Clinicians can create environments that could reduce anxiety, increase emotional engagement, and stimulate real-world challenges that can be faced outside the clinic [6]. The flexibility that VR provides allows it to create a positive feedback loop; increased engagement leads to more meaningful usage, which strengthens neural networks, in turn leading to further motivation and functional improvement [46]. VR represents an impactful therapeutic modality that combines embodiment, engagement, and emotions in ways that are beyond traditional therapy [46]. VR technology makes personalized, immersive, and transformative neurorehabilitation more achievable [6, 46].

References

Alessandro, C., Beckers, N., Goebel, P., Resquin, F., González, J., & Osu, R. (2015). Motor Control and Learning Theories. Biosystems & Biorobotics, 225-250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24901-8_9

Shen, Y., Jiang, L., Lai, J., Hu, J., Liang, F., Zhang, X., & Ma, F. (2025). A comprehensive review of rehabilitation approaches for traumatic brain injury: Efficacy and outcomes. Frontiers in Neurology, 16. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1608645

Bateni, H., Carruthers, J., Mohan, R., & Pishva, S. (2024). Use of virtual reality in physical therapy as an intervention and diagnostic tool. Rehabilitation Research and Practice, 1-9. doi: 10.1155/2024/1122286

Wojciechowski, A., & Korjonen-Kuusipuro, K. (2022). Rehabilitation in digital environments – biophysiologically motivated gamification. Human Technology, 18(3), 209-212. doi: 10.14254/1795-6889.2022.18-3.1

Hamad, A., & Jia, B. (2022). How Virtual Reality Technology Has Changed Our Lives: An Overview of the Current and Potential Applications and Limitations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18). doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811278

Catania, V., Rundo, F., Panerai, S., & Ferri, R. (2024). Virtual Reality for the Rehabilitation of Acquired Cognitive Disorders: A Narrative Review. Bioengineering, 11(1), 35. doi:10.3390/bioengineering11010035

Drigas, A., & Sideraki, A. (2024). Brain Neuroplasticity Leveraging Virtual Reality and Brain-Computer Interface Technologies. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 24(17), 5725. doi:10.3390/s24175725

Georgiev, D., Georgieva, I., Gong, Z., Nanjappan, V., & Georgiev, G. (2021). Virtual Reality for Neurorehabilitation and Cognitive Enhancement. Brain Sciences, 11(2), 221. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11020221

Rabinovici, G. D., Stephens, M. L., & Possin, K. L. (2015). Executive dysfunction. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.), 21(3), 646–659. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000466658.05156.54

Cowan, N., Bao, C., Bishop-Chrzanowski, B. M., Costa, A., Greene, N. R., Guitard, D., Li, C., Musich, M., & Ünal, Z. E. (2023). The Relation Between Attention and Memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 75(1). doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-040723-012736

Harvey, P. (2019). Cognition in Mental Health. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 21(3). doi: 10.31887/dcns.2019.21.3

Shi, Y., & Qu, S. (2021). Cognitive Ability and Self-Control’s Influence on High School Students’ Comprehensive Academic Performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783673

Shi, L. (2024). Research on the impact of virtual reality games on cognitive abilities. Transactions on Computer Science and Intelligent Systems Research, 7, 44–48. doi: 10.62051/qkn7tx27

Keshner, E. A., & Lamontagne, A. (2021). The Untapped Potential of Virtual Reality in Rehabilitation of Balance and Gait in Neurological Disorders. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 2. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2021.641650

Maggio, M. G., Bonanno, L., Rizzo, A., Barbera, M., Benenati, A., Impellizzeri, F., Corallo, F., De Luca, R., Quartarone, A., & Calabrò, R. S. (2025). The role of virtual reality-based cognitive training in enhancing motivation and cognitive functions in individuals with chronic stroke. Scientific Reports, 15(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-08173-1

Quan, W., Liu, S., Cao, M., & Zhao, J. (2024). A Comprehensive Review of Virtual Reality Technology for Cognitive Rehabilitation in Patients with Neurological Conditions. Applied Sciences, 14(14), 6285. doi: 10.3390/app14146285

Fang, C., Lv, L., Mao, S., Dong, H., & Liu, B. (2020). Cognition deficits in parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms and treatment. Parkinson’s Disease, 2020(1), 1-11. doi: 10.1155/2020/2076942

Chan, A., Ouyang, J., Nguyen, K., Jones, A., Basso, S., & Karasik, R. (2024). Traumatic brain injuries: a neuropsychological review. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 18. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2024.1326115

Muñoz, D., Barria, P., Cifuentes, C. A., Aguilar, R., Baleta, K., Azorín, J. M., & Múnera, M. (2022). EEG Evaluation in a Neuropsychological Intervention Program Based on Virtual Reality in Adults with Parkinson's Disease. Biosensors, 12(9), 751. doi: 10.3390/bios12090751

Zanier, E. R., Zoerle, T., Di Lernia, D., & Riva, G. (2018). Virtual Reality for Traumatic Brain Injury. Frontiers in Neurology, 9. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00345

Teo, W.-P., Muthalib, M., Yamin, S., Hendy, A. M., Bramstedt, K., Kotsopoulos, E., Perrey, S., & Ayaz, H. (2016). Does a combination of virtual reality, neuromodulation and neuroimaging provide a comprehensive platform for neurorehabilitation? – A narrative review of the literature. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00284

Richlan, F. (2025). Behavioral and neuroanatomical effects of soccer heading training in virtual reality: A longitudinal fMRI case study. Neuropsychologia, 211, 109124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2025.109124

Tremmel, C., Herff, C., Sato, T., Rechowicz, K., Yamani, Y., & Krusienski, D. J. (2019). Estimating Cognitive Workload in an Interactive Virtual Reality Environment Using EEG. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00401

Liu, X.-Y., Wang, W.-L., Liu, M., Chen, M.-Y., Pereira, T., Doda, D. Y., Ke, Y.-F., Wang, S.-Y., Wen, D., Tong, X.-G., Li, W.-G., Yang, Y., Han, X.-D., Sun, Y.-L., Song, X., Hao, C.-Y., Zhang, Z.-H., Liu, X.-Y., Li, C.-Y., … Ming, D. (2025). Recent applications of EEG-based brain-computer-interface in the medical field. Military Medical Research, 12(1). doi: 10.1186/s40779-025-00598-z

Wang, Y., Weng, T., Tsai, I., Kao, J., & Chang, Y. (2022). Effects of virtual reality on creativity performance and perceived immersion: A study of brain waves. British Journal of Educational Technology. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13264

Rueda-Castro, V., Chacon, J., Azofeifa, J. D., Caratozzolo, P., & Camacho-Leon, S. (2025). Modulation of alpha and theta waves by social stimuli in virtual educational environments. Scientific Reports, 15(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-13027-x

Moulaei, K., Sharifi, H., Bahaadinbeigy, K., & Dinari, F. (2024). Efficacy of virtual reality-based training programs and games on the improvement of cognitive disorders in patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1). doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05563-z

Eggenberger, P., Schumacher, V., Angst, M., Theill, N., & de Bruin, E. (2015). Does multicomponent physical exercise with simultaneous cognitive training boost cognitive performance in older adults? A 6-month randomized controlled trial with a 1-year follow-up. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 1335-1349. doi: 10.2147/cia.s87732

Zhang, B., Li, D., Liu, Y., Wang, J., & Xiao, Q. (2021). Virtual reality for limb motor function, balance, gait, cognition and daily function of stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of advanced nursing, 77(8), 3255–3273. doi: 10.1111/jan.14800

Nettles, G., Greene, R., Cancer, A., & Stasher-Booker, B. (2023). Physical Therapy. Springer EBooks, 85-97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-40889-2_6

Calabrò, R. S., Naro, A., Russo, M., Leo, A., De Luca, R., Balletta, T., Buda, A., La Rosa, G., Bramanti, A., & Bramanti, P. (2017). The role of virtual reality in improving motor performance as revealed by EEG: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 14(1). doi: 10.1186/s12984-017-0268-4

Jacobson, S., Marcus, E. M., & Pugsley, S. (2017). Motor System, Movement, and Motor Pathways. Springer EBooks, 331-360. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-60187-8_11

Fink, K. L., & Cafferty, W. B. J. (2016). Reorganization of Intact Descending Motor Circuits to Replace Lost Connections After Injury. Neurotherapeutics, 13(2), 370-381. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0422-x

Inoue, T., & Ueno, M. (2025). The diversity and plasticity of descending motor pathways rewired after stroke and trauma in rodents. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 19. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2025.1566562

Naqvi, W. M., Naqvi, I., Mishra, G. V., & Vishnu Vardhan. (2024). The Dual Importance of Virtual Reality Usability in Rehabilitation: A Focus on Therapists and Patients. Curēus, 16(3). doi: 10.7759/cureus.56724

Schalbetter, L., Grêt-Regamey, A., Gutscher, F., & Wissen Hayek, U. (2025). High-fidelity immersive virtual reality environments for gait rehabilitation exergames. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 5. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2024.1502802

Atilla, F., Postma, M., & Alimardani, M. (2024). Gamification of Motor Imagery Brain-Computer Interface Training Protocols: a systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 100508-100508. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2024.100508

Wen, X., Li, L., Li, X., Zha, H., Liu, Z., Peng, Y., Liu, X., Liu, H., Yang, Q., & Wang, J. (2022). Therapeutic role of additional mirror therapy on the recovery of upper extremity motor function after stroke: A single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Neural Plasticity, 2022, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2022/8966920

Özen, Ö., Buetler, K. A., & Marchal-Crespo, L. (2022). Towards functional robotic training: motor learning of dynamic tasks is enhanced by haptic rendering but hampered by arm weight support. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 19(1). doi: 10.1186/s12984-022-00993-w

Jo, S., Jang, H., Kim, H., & Song, C. (2024). 360° immersive virtual reality-based mirror therapy for upper extremity function and satisfaction among stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 60(2), 207-215. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.24.08275-3

Nagamine, T. (2025). Challenges in using virtual reality technology for pain relief. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 13(16). doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i16.103372

Sokołowska, B. (2024). Being in Virtual Reality and Its Influence on Brain Health—An Overview of Benefits, Limitations and Prospects. Brain Sciences, 14(1), 72. doi: 10.3390/brainsci14010072

Riva, G., Wiederhold, B. K., & Mantovani, F. (2019). Neuroscience of virtual reality: From virtual exposure to embodied medicine. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(1). doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.29099.gri

Park, S. Y., Kim, S. M., Roh, S., Soh, M.-A., Lee, S. H., Kim, H., Lee, Y. S., & Han, D. H. (2016). The effects of a virtual reality treatment program for online gaming addiction. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 129, 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.01.015

Speranza, L., di Porzio, U., Viggiano, D., de Donato, A., & Volpicelli, F. (2021). Dopamine: The Neuromodulator of Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity, Reward and Movement Control. Cells, 10(4), 735. doi: 10.3390/cells10040735

Wankhede, N. L., Sushruta Koppula, Bhalla, S., Doshi, H., Rohit Kumawat, Raju, Ss., Arora, I., Sammeta, S. S., Khalid, M., Zafar, A., Taksande, B. G., Upaganlawar, A. B., Gulati, M., Umekar, M. J., Spandana Rajendra Kopalli, & Kale, M. B. (2024). Virtual reality modulating dynamics of neuroplasticity: Innovations in neuro-motor rehabilitation. Neuroscience. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.12.040

Sramka, M., Lacko, J., Ruzicky, E., & Masan, J. (2020). Combined methods of rehabilitation of patients after stroke: virtual reality and traditional approach. Neuro Endocrinology Letters, 41(3), 123–133. PMID: 33201645

Zhao, J., Guo, J., Chen, Y., Li, W., Zhou, P., Zhu, G., Han, P., & Xu, D. (2024). Improving rehabilitation motivation and motor learning ability of stroke patients using different reward strategies: study protocol for a single-center, randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Neurology, 15. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1418247

Navas-Otero, A., Canal-Pérez, A., Martín-Núñez, J., Ortiz-Rubio, A., Raya-Benítez, J., Valenza, M. C., & Cabrera-Martos, I. (2025). Rehabilitation applied with virtual reality improves functional capacity in post-stroke patients. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rehabilitación, 59(2), 100907. doi: 10.1016/j.rh.2025.100907

Jehl, N. M., Hess, C. W., Choate, E. S., Nguyen, H. T., Yang, Y., & Simons, L. E. (2024). Navigating virtual realities: identifying barriers and facilitators to implementing VR-enhanced PT for youth with chronic pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsae056

Capriotti, A., Moret, S., Del Bello, E., Federici, A., & Lucertini, F. (2025). Virtual Reality: A New Frontier of Physical Rehabilitation. Sensors, 25(10), 3080. doi: 10.3390/s25103080

Wiederhold, B. K. (2020). Embodiment Empowers Empathy in Virtual Reality. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(11), 725–726. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.29199.editorial

Matamala-Gomez, M., Donegan, T., Bottiroli, S., Sandrini, G., Sanchez-Vives, M. V., & Tassorelli, C. (2019). Immersive Virtual Reality and Virtual Embodiment for Pain Relief. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00279

Ventura, S., Marchetti, P., Baños, R., & Tessari, A. (2023). Body ownership illusion through virtual reality as modulator variable for limbs rehabilitation after stroke: A systematic review. Virtual Reality, 27(3), 2481–2492. doi: 10.1007/s10055-023-00820-0

Tong, Z. (2016). Virtual Reality in Neurorehabilitation. International Journal of Neurorehabilitation, 3(1). doi: 10.4172/2376-0281.1000e117

Kwon, S. H., Park, J. K., & Koh, Y. H. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of virtual reality-based rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation, 20(1). doi: 10.1186/s12984-023-01219-3

Ramesh, S., & Arachchige, A. S. (2023). Depletion of dopamine in parkinson’s disease and relevant therapeutic options: A review of the literature. AIMS Neuroscience, 10(3), 200–231. doi: 10.3934/neuroscience.2023017

Triegaardt, J., Han, T. S., Sada, C., Sharma, S., & Sharma, P. (2019). The role of virtual reality on outcomes in rehabilitation of Parkinson’s disease: meta-analysis and systematic review in 1031 participants. Neurological Sciences, 41(3), 529-536. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-04144-3

Pezzetta, R., Ozkan, D. G., Era, V., Tieri, G., Zabberoni, S., Taglieri, S., Costa, A., Peppe, A., Caltagirone, C., & Aglioti, S. M. (2023). Combined EEG and immersive virtual reality unveil dopaminergic modulation of error monitoring in Parkinson's Disease. NPJ Parkinson's disease, 9(1), 3. doi: 10.1038/s41531-022-00441-5

Cristofori, I., & Levin, H. S. (2015). Traumatic brain injury and cognition. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 128, 579-611. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63521-1.00037-6